Note: This article is adapted from a post originally published in July 2017 in conjunction with the Beinecke Library’s exhibition of photographs of the 1917 Silent Protest Parade to commemorate its centennial.

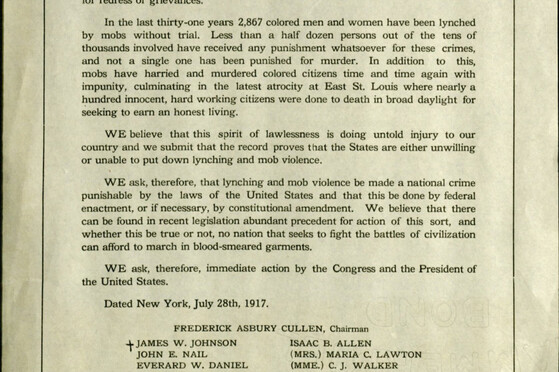

The collection features the petition signed by eleven of the members of the committee who traveled to Washington, D.C., to present it to President Wilson on August 1, 1917: John E. Nail, James Weldon Johnson, Everard W. Daniel, George Frazier Miller, Fred R. Moore, A. B. Cosey, D. Ivison Hoage, Isaac B. Allen, Maria C. Lawton, Madam C. J. Walker, and Frederick A. Cullen (chairman). As the printed version of the petition notes, the committee was turned away by J. P. Tumulty, Secretary to the President, who said that Wilson was “too busy” to receive the delegation.

The events in East St. Louis provided a preview for the terrible summer of 1919, when white supremacist violence broke out in cities throughout the country including Chicago, Washington, D.C., Omaha, Nebraska, and Knoxville, Tennessee. Johnson gave the season of horror its name: “Red Summer.” But, in spite of that reversal, the Silent Protest Parade had established the organization of mass protest as possible. As Johnson wrote in his autobiography Along this Way: “The streets of New York have witnessed many strange sights, but, I judge, never one stranger than this; certainly, never one more impressive.”