Underneath the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, dozens of posters, diaries, letters, article and books are arranged on tables around the reading room, in chronological order from the antislavery movement to the civil rights movement, representing the background to the work Martin Luther King Jr. did. Every Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the Beinecke opens the doors to the public to view their most relevant and prominent items related to the history. After leaving my coat and backpack upstairs locked in a locker with the password “2008,” I step into the quiet room, which is full of an air of reverence.

Out of the tens of thousands of artifacts relevant for this exhibition, curators at the Beinecke chose the highlights of their collections of African-American literature and thought, particularly material relating to New Haven and typed or photographic material that would be easiest for visitors to read. On one table you could find the pen used by Abraham Lincoln to sign the Emancipation Proclamation and a middle-aged woman studying it closely. Lincoln had randomly passed off the pen to another after signing the proclamation, and the man who had taken it passed it down through generations of his family. On the other end lays a pencilled and crossed-out draft of Langston Hughes’ poem “I, Too,” which, earlier that day, I had been reading in a literature class.

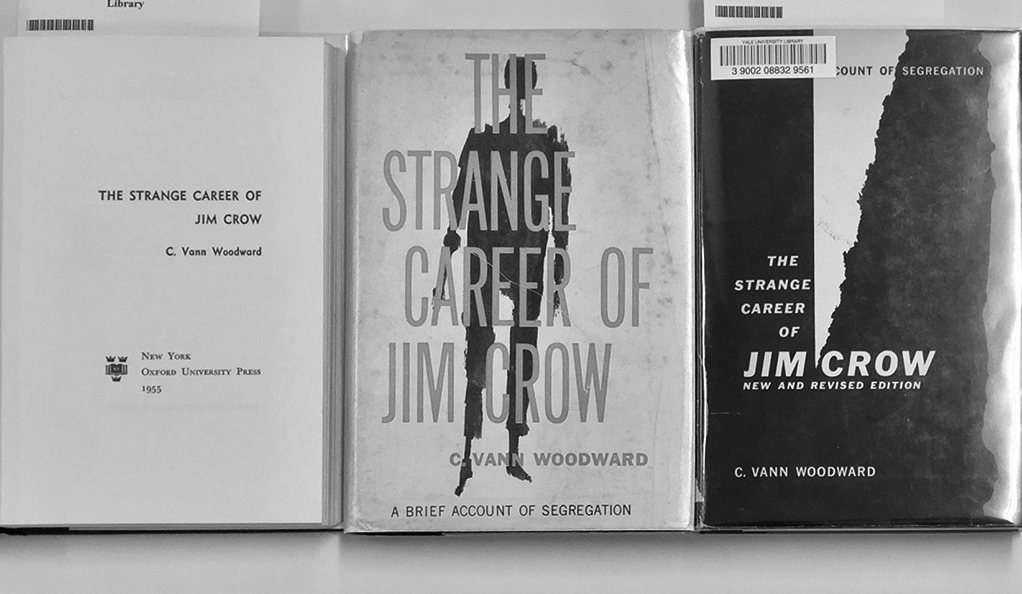

The material is roughly organized in chronological order, beginning with the autobiography of William Grimes, a yellowing 1825 original copy of the first narrative to be written and published by a slave. Grimes, who handled this very edition, escaped slavery in Virginia and fled to New York, walked to New Haven and became a barber. The papers traverse through the antislavery movement, the Niagara Movement and the Harlem Renaissance, representing the background and work leading up to the civil rights movement.

Yale has one of the largest collections of African-American literature and papers, Moira Fitzgerald, head of access services for the Beinecke, told me. One of their most comprehensive collections is papers from the Harlem Renaissance, largely due to the influence of James Weldon Johnson, a college professor at Fisk University and author of “The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man,” who believed that literature, culture and writing was the way for African-Americans to make their way in the world.

When Johnson suddenly died in a car crash in 1924, Carl Van Vechten, one of Johnson’s close friends and a white photographer, writer and mentor for many artists during the Harlem Renaissance, founded the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of American Negro Arts and Letters made up of Johnson’s papers, Vechten’s books and various memorabilia, including papers from authors including Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. This collection made up the first, and the largest, archive of African-American papers at the University, and nearly a century later, it is still revered.

In 1950, when Yale officially opened the first parts of the archival material, the University was a primarily white and male institution. It was a controversial move to accept this cache of African-American papers, as was Yale’s decision in 1964 to award an honorary degree to King. Fitzgerald noted that there are letters in the Kingman Brewster papers at the Manuscripts and Archives from donors saying they stopped giving money to the University for doing this and from donation collectors in the South whose patrons refused to support the University any longer. While the long movement for full racial equality still continues, the people of Yale and their relation to questions of race have changed, this collection shows.

One by one, the original texts, words and papers of African-American leaders and scholars follow around the room, from Grimes to Frederick Douglass to Hughes to William Pickens, class of 1904, to James Baldwin to Rita Dove. Traces of their lives mark the pages: Their words in original handwriting, notes scribbled in margins, Hughes’ large signature decorating the bottom of the page, words underlined and crossed out in Baldwin’s letter to his sister.

Adults of all ages, all ethnicities, peer at the papers with reverence. Years of sweat and tears and blood and marches and anger and fervor and hope distilled in a quiet, clean room, half a century later, in the celebrated library of an institution that continues to reckon with its own racial history. Posters in brilliant colors with faces raised in solidarity, faces of people no longer in this world. All for a moment outside of forgotten archival rooms and observed by others.

We preserve the past, and we respect these physical objects because there is something special about the real thing: the real pen she touched, the original poem he wrote, the century-old Yale diploma with dark, fraying edges. It matters that we see these decaying objects, that we put our faces close to them, instead of reading a blurb in a book, staring at a picture on the screen. They take our breath away with their ordinariness, with their fragility. The past is closer and further from the present than we’d like to think. For a moment, we can cluster around the past and reckon with the long, long journey it took to get to this moment we share.

Helena Lyng-Olsen | helena.lyngolsen@yale.edu .