The Historical Printing and Signing of the U.S. Declaration of Independence

Beginning in June 1776, drafts of the historical document were made, printed, and later signed and disseminated to help declare America’s independence.

Beginning in June 1776, something remarkable was happening at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia. The Second Continental Congress was meeting to consider severing the colonies’ ties to the British Crown.

On June 7th, Richard Henry Lee introduced a resolution urging Congress to declare independence from Great Britain.

On June 11th, the so-called Committee of Five, comprised of Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston, were appointed to draft a declaration of independence.

They created a rough draft of the document which is in Thomas Jefferson’s handwriting. A copy of that document is at the Library of Congress.

By June 28th, a draft of the committee’s Declaration of Independence was read to the Congress, who then debated and revised it. On July 2nd, Congress took the extraordinary step and declared independence by adopting the Lee Resolution.

The first copies are printed

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence and ordered that it be printed and copies disseminated to the colonies.

The copies were printed by the Philadelphia printer John Dunlap on the evening of July 4, 1776, and they are called the Dunlap Broadsides.

A broadside was a large sheet of paper printed on only one side that was used for a poster, announcement of events or proclamations, commentary or advertisement.

The broadsides were distributed to the Committees of Safety in every colony, as well as to the head of the Continental Army, General George Washington. It was the first public version and the first published version of the text, and it was the version that printers relied on for later editions.

RELATED: 7 OF THE MOST IMPORTANT OF BEN FRANKLIN’S ACCOMPLISHMENTS

In 1949, there were 14 copies of the Dunlap Broadside known to exist. By 2009, there were 25 known copies, as well as a “proof” copy at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Below are the institutions and individuals possessing a copy of a Dunlap Broadside:

* Beinecke Library, Yale University (New Haven, CT)

* Library of Congress (1 copy plus fragment copy; Washington, D.C.)

* National Archives (Washington, DC)

* Lilly Library, Indiana University (Bloomington, IN)

* Chicago Historical Society (Chicago, IL)

* Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston, MA)

* Houghton Library, Harvard University (Cambridge, MA)

* Williams College (Williamstown, MA)

* Maryland Historical Society (fragment; Baltimore, MD)

* Maine Historical Society (Portland, ME)

* American Independence Museum (Exeter, NH)

* Scheide Library, Princeton University (owner: William R. Scheide; Princeton, NJ)

* Morgan Library (New York, NY)

* New York Public Library (New York, NY)

* Private Collector (last known location: New York, NY)

* American Philosophical Society (Philadelphia, PA)

* Independence National Historical Park (Philadelphia, PA)

* Dallas Public Library (Dallas, TX)

* University of Virginia (2 copies; Charlottesville, VA)

* Norman Lear et. al. (Roving)

* The National Archives (3 copies; London, United Kingdom)

On Saturday, July 6th, the Pennsylvania Evening Post, which was printed by Benjamin Towne, had gotten a copy of the text of the Declaration, and Towne printed the Declaration of Independence as front-page news.

A newspaper version is how many Americans would have read the text of the Declaration. Several institutions and private parties own copies of this newspaper version.

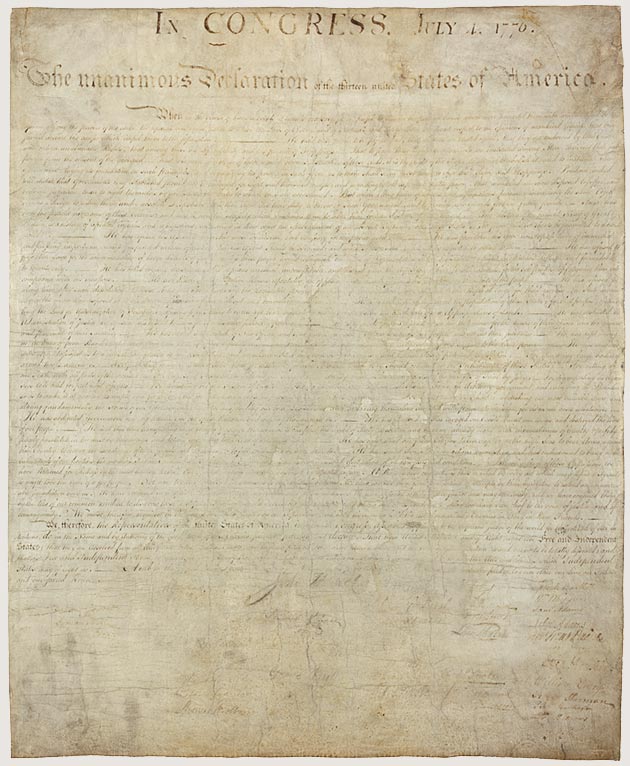

On July 19th, Congress ordered that the Declaration of Independence be officially “engrossed,” meaning that it be written on parchment and signed by delegates. The engrosser was most likely Timothy Matlack, an assistant to Secretary Charles Thomson.

On August 2nd, the engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence was signed by most of the delegates to the Congress. Five delegates, Elbridge Gerry, Oliver Wolcott, Lewis Morris, Thomas McKean, and Matthew Thornton signed on a later date.

The signed version goes on the road

The parchment was entrusted to Charles Thomson, who rolled it up and carried it along with other documents as the Continental Congress moved locations over the course of the Revolutionary War.

After the war, the parchment was given to the office of the Secretary of State, who was Thomas Jefferson.

Today, the now-faded parchment resides in the National Archives, along with the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

In mid-December 1776, British troops were closing in on Philadelphia, and the Continental Congress evacuated to Baltimore, Maryland.

In January 1777, Baltimore’s postmaster, Mary Katherine Goddard, was tasked with printing broadsides of the signed Declaration. Not only did she print it, but she placed her name at the bottom of the document. Had the British won the war, this act would have placed her along with the signatories in grave danger.

On January 31, 1777, President of Congress John Hancock sent a copy of the broadside to each of the states, accompanied by the following letter:

“As there is not a more distinguished Event in the History of America, than the Declaration of her Independence–nor any that in all Probability, will so much excite the Attention of future Ages, it is highly proper that the Memory of that Transaction, together with the Causes that gave Rise to it, should be preserved in the most careful Manner that can be devised. I am therefore commanded by Congress to transmit you the enclosed Copy of the Act of Independence with the List of the several Members of Congress subscribed thereto and to request, that you will cause the same to be put upon Record, that it may henceforth form a Part of the Archives of your State, and remain a lasting Testimony of your approbation of that necessary & important Measure.”

A newspaper version goes on display

Just recently, an extremely rare 1776 printing of the Declaration of Independence has gone on display to the public. This is the first time in over a century that this copy has been seen, and it is the first time that it has been displayed in a museum.

This copy of the Declaration was printed by newspaper publisher and printer John Holt in New York in 1776. It is addressed to Col. David Mulford, who was a Revolutionary War colonel, who died of smallpox in 1778.

Amazingly, the print stayed in the Mulford family’s possession until 2017, when it was sold to Holly Metcalf Kinyon, who is herself a descendant of a signer of the Declaration, John Witherspoon.

Kinyon praised the women of Mulford’s family who were instrumental in preserving the print. It is on display at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia through the end of 2019.

Two remarkable discoveries

In April 2017, a remarkable discovery was made by two Harvard University researchers, Danielle Allen, and Emily Sneff. They found a parchment manuscript of the U.S. Declaration of Independence in a records office in Sussex County, England.

Called “The Sussex Declaration,” it was most likely produced a decade later than the original that is in the National Archives, and unlike the original, it is oriented horizontally. Also, unlike the original, the signatories are not grouped by state, and John Hancock’s signature is the same size as the other signatures.

Allen and Sneff believe that the Sussex Declaration was owned by the Third Duke of Richmond, who was a known supporter of the Americans during the revolution.

In 1989, one of the original Dunlap broadsides was discovered hidden behind a torn painting that was sold for $4 at a flea market in Adamstown, Pennsylvania. When the new owner removed the painting, they found the Declaration folded behind the painting.

In 1991, it was auctioned by Sotheby’s for an eye-watering $2,420,000, or about $4,000,000 in today’s dollars.

SHOW COMMENT ()

SHOW COMMENT ()