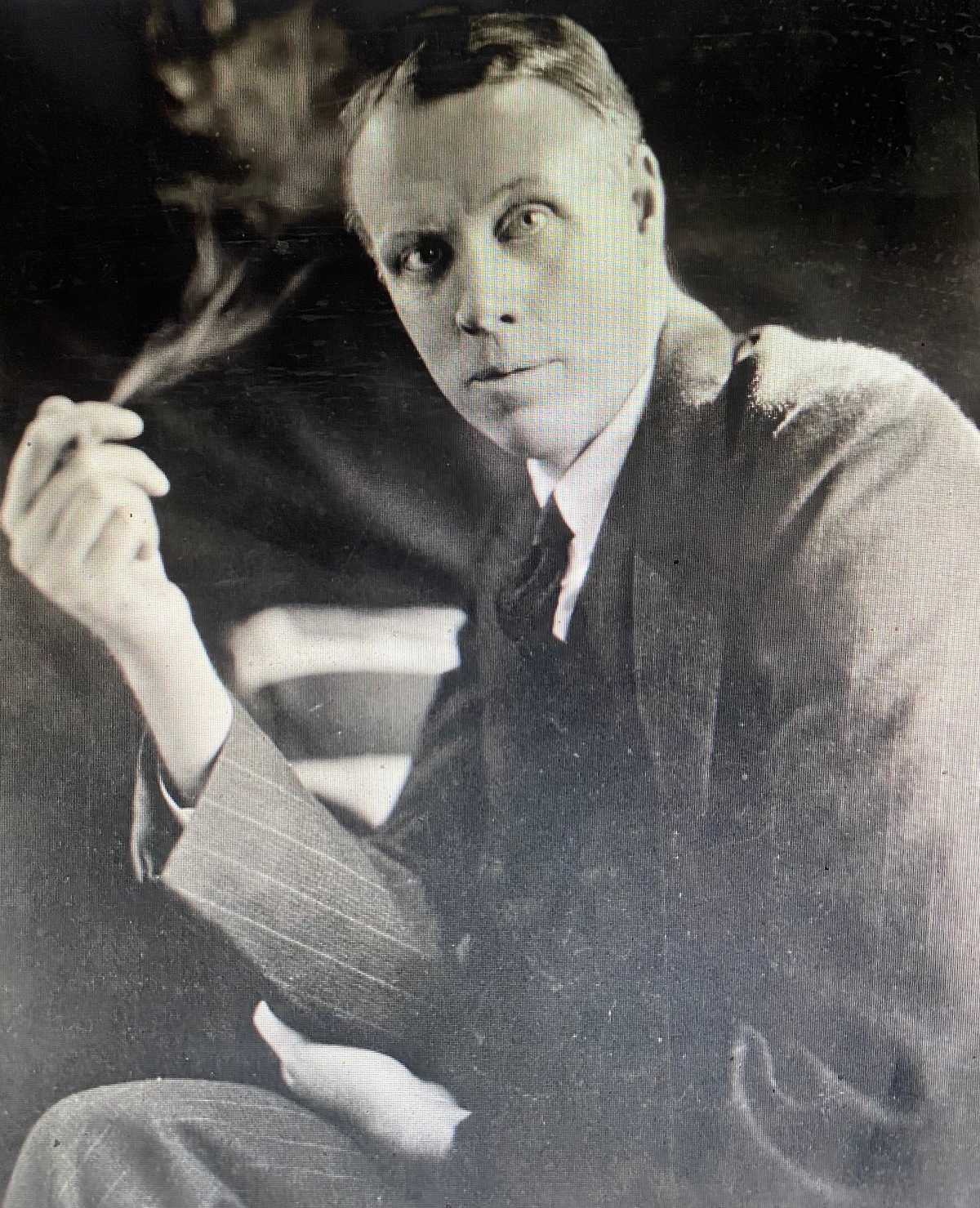

Future imperfect: Sinclair Lewis.

Lately, like a truffle dog on the hunt, I have sniffed along the New Haven trail of the first American to receive the Nobel Prize for literature.

The search led me to Yale’s Old Campus, where Harry Sinclair Lewis took his bachelor’s degree in 1908; up to the summit of East Rock, where his imagination flourished; down to the reading room of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where his papers are store; and finally to his forecast of the advent of Donald Trump.

I should, however, back up a moment before leading you on this trek through literary triumph to the depths of dystopia.

In my formative years, I was a Sinclair Lewis fan without appreciating why this was so. Two of his signature novels, Main Street and Babbitt, engaged me through its characters, plots and descriptions, though at the time I was only a tourist in the land of social satire.

After a gap of several decades and diversions to more contemporary literature, I returned to see if I could make more of the Lewis oeuvre.

At the suggestion of friends, I started with Dodsworth. It is a lesser celebrated work but first-rate in terms of character development and wit, detailing the life in middle age of an industrial magnate who, when he retires, must navigate unfamiliar turf.

Sam Dodsworth’s wife, Fran, a decade younger yet worried about fading feminine appeal, becomes desperate to follow all of her instincts before it’s too late. She convinces Sam to explore Europe, to engage with the continent’s high society and art world, and makes him a witness to her flirtations with men who sweep her off of her feet in the most literal way.

It is in that novel that Lewis, through the rich character of the mentally lost protagonist, recalls his days atop East Rock, sitting on a bench near the Civil War monument, and looking out over the Elm City and Long Island Sound toward what a young mind from rural Minnesota imagined of Europe and beyond.

As it turned out, in time his curiosity, instincts and family circumstance allowed him to see into America’s future in a way that has turned him into a prognosticator.

In 1935, another time of significant peril in our country — the depths of the Depression, tens of millions out of work and stripped of dignity, an enormous wave of racism and anti-Semitism spewed by persuasive forces, and the spreading influences of autocratic thinking following the rise of Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin — the author released the last of his novels considered to be masterpieces.

Titled ironically It Can’t Happen Here, it became a best seller just as Babbitt, Main Street, Arrowsmith, and Elmer Gantry. But it was different. Even with its inevitable sparks of humor, it was dark and hair-raising and, alas, nearly a century after its first publication, accurate.

It foretold specifically the election of the following year, 1936, and the presidency of “Buzz” Windrip, a populist with a gift for gab, and intentions of despotism. Like Donald Trump many decades later, he would consolidate power, encourage bigotry, make use of every weapon available to him to undercut enemies.

And like Trump, he would do much of it in the open by appealing to the darkest and greediest side of white American Christians.

He publishes a 15-point plan for America that promises prosperity and a $5,000 cash gift for each family. It also specifies that Blacks must turn every penny they earn over $10,000 to the IRS, and that Jews are deserving targets of discrimination as payback, in his accounting, for pilfering billions from Christians.

In foreign policy, it was America First and Only. In general governmental scope practice, Hitler provided a sound model. It is the effective politics of grievance, fear, greed, lies, press censorship, xenophobia, retribution, oppression, and of always having a lower class to beat down and exploit.

Windrip’s appeal is described by the narrator in way that seems familiar today:

“He was an actor of genius. There was no more overwhelming actor on the stage, in the motion pictures, nor even in the pulpit. He would whirl arms, bang tables, glare from mad eyes, vomit Biblical wrath from a gaping mouth; but he would also coo like a nursing mother, beseech like an aching lover, and in between tricks would coldly and almost contemptuously jab his crowds with figures and facts — figures and facts that were inescapable even when, as often happened, they were entirely incorrect.”

When Windrip takes power, his policies churn Congress and the judicial system into dust, leaving him as the unchallenged ruler, enabling his paramilitary forces to crush dissent.

The really shocking part, the one that registers throughout America today, is that by spewing fear and grievance, he convinces the majority of citizens initially to support him.

Initial reaction to the novel in 1935 was impressive; 320,000 copies were sold. Clifton Fadiman, then the head of the New Yorker magazine’s book review section, called it “one of the most important books ever produced in this country.” His assessment proved correct in at least one respect. It has endured.

Following Trump’s election, Penguin reissued It Can’t Happen Here. It became a bestseller again, this time on Amazon’s list of most popular books of 2017. Scholars and pundits have pointed to it as visionary and required reading.

In The Washington Post, book critic Carlos Lozada compared Trump to Windrip: “It is impossible to miss the similarities between Trump and totalitarian figures in American literature.” Jacob Weisberg wrote in Slate that one “can’t read Lewis’s novel today without flashes of Trumpian recognition.”

In 2018, HarperCollins published Can It Happen Here?: Authoritarianism in America. The following year, Robert Evans produced the podcast, “It Can Happen Here.” And in 2021, New York University published a book with the same title, written by genocide scholar Alexander Laban Hinton.

To find out more about Lewis’s effort to predict such dire circumstance, I became a denizen of the Beinecke, the 1963 building of translucent marble and granite on Yale’s Hewitt Quadrangle. Here, there are priceless relics available to examine by any visitor. These include one of the few extant copies of the original Gutenberg Bible and John James Audubon’s The Birds of America.

Downstairs in the Reading Room, researchers fill the tables and examine materials from a Who’s Who list of luminaries of all professions and includes that of writers such as Joseph Conrad, Rachel Carson, Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, Langston Hughes, and Edith Wharton.

The Sinclair Lewis collection consists of dozens of boxes of manuscripts, letters, diaries, photographs, and notes, a goldmine for those with the time and interest in what it took for Lewis to reach the top of the literary world in two consecutive centuries.

I had to stop for a minute, feeling a sense of awe, while turning the original typed pages of It Can’t Happen Here. Those yellowed sheets show the author’s own edits — the cross-outs, the altered language, the additions — he felt he needed before sending the manuscript to his publisher.

How, I wondered, had he become so informed about the Hitler dangers as they related to the U.S., when so much of this country was blind to them, and support for them showed up in the voices of influential broadcasters of venom such as Father Coughlin?

If I had read any of the three biographies of Lewis, I would have known already.

Lewis’s wife at the time was Dorothy Thompson, one of the most accomplished journalists and broadcasters of the era. She had reported from Germany on Hitler’s rise, and was the first American reporter to interview him.

For her dogged efforts at covering the ascent of Nazism, she was expelled from Germany. She returned home to write further and to provide insight on the causes and effects of autocracy to her husband.

It has been until now a foolish and unreasonable stretch to put the words Hitler and Trump in the same sentence. Such a references diminishes the extent of the cataclysmic deeds of the man who incited The Final Solution. But …

Levels of evil tend to blur when the pressure is on. Today, grievance and revenge are in the air. America has more guns than people. Militias are driven by the ideal of white supremacy. They are standing by. And, as we saw on Jan. 6, 2021, up to worse.

Our system of laws has so far prevented Trump from carrying out many of his known and unknown intentions, but it offers no lens for examining the desires and designs of an evil heart.

Sinclair Lewis, for all of his masterful ways of showing how words can spawn delight, also knew that the tools that took him to the Nobel medal could also be twisted, used to hide truths, to exaggerate and minimize, and could from the mouth of a malevolent populist lead to ruin before distracted citizens recognize the danger.

I suspect if Lewis had lived another seven decades (he died in 1951), he might have published, It’s Already Happening Here.

Lary Bloom’s new book, “I’ll Take New Haven,” a collection of essays published on this site, will be released by Antrim House in October.

Many left leaning liberals are mistakenly supporting the most outrageous candidates in the far right in the primaries, in the mistaken assumption that it would encourage more moderate republican voters and complacent democratic voters to vote for those opponents of the far right candidates on the democratic ticket.

But nobody thought Trump could win, they were positive that Hillary would win the vote. They underestimated the influence of social media algorithms, right wing media outlets, the radicalization of hatred and discrimination and the fear of the collapse of the ability to achieve middle class aspirations.

Top it off with a pandemic and inflation, and the fact that Gen X, Millennials and Gen Z will have higher debt and a lower standard of living than their parents or grandparents, and you have a hugely dissatisfied population ripe for revolution and grasping at whatever candidate promises falsely to take us back to the “good old days” when our nation post WWII, was thriving if you were white, Christian, straight, and cisgender male.

Website operators, media figureheads and white supremacists are weaponizing the internet and the media outlets for profit.

Foreign adversarial nations like Russia, China, Iran and North Korea have state sponsored misinformation, disinformation and propaganda campaigns to turn Americans against each other and bring out the worst in us to make our nation weak and bring us to civil war once again.

The right wing are putting in place candidates for local offices that would oversee and overturn elections, rollback civil rights, and manipulate the votes and nominate judges and candidates that will do their bidding.

If we aren’t careful, we will have a far worse situation than we had the previous administration, where they almost had a coup. Be forewarned, they have learned from their mistakes and are preparing to not fail

in the midterms or in the next presidential election to overthrow our government.