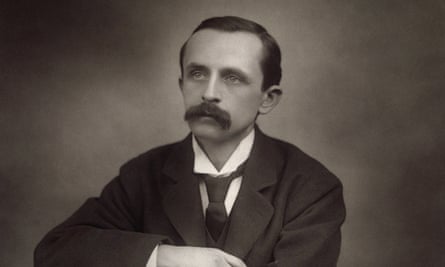

They are two of the greatest writers in history and they were also the greatest of friends. But they never met, and the importance and intensity of their relationship has never before been fully understood.

Now, the letters of JM Barrie to Robert Louis Stevenson – presumed to be lost by several key Barrie biographers for over 70 years - will be published for the first time in a forthcoming book. The letters reveal how ardently the young Barrie both adored and admired Stevenson, who was an older and more established writer. A year into their friendship, which was initiated by Stevenson, Barrie wrote to him: “To be blunt I have discovered (have suspected it for some time) that I love you, and if you had been a woman...” He leaves the sentence unfinished.

He also imagines in the letters that he and Stevenson are related and were descended from the same Scottish family, a fantasy that allows him to open up to the older man about the intimacies of his family life and his close relationship with his mother.

Treasure Island had already been published when the two authors began corresponding in 1892; 12 years later, Barrie went on to write his own masterpiece, Peter Pan, about a dangerous amputated pirate, a young boy and a journey to a far-off fantasy island.

He repeatedly fantasises in his letters about meeting Stevenson, who had left their native Scotland in 1879 and was living in Samoa to improve his health. In one previously unpublished letter, Barrie even writes a funny, self-deprecating playlet in which he imagines himself visiting Stevenson’s 314-acre estate, and Stevenson “glumly” saying to his wife about Barrie: “Perhaps he will improve after he has rested a bit.”

In reality, Barrie was held back from ever making that thrilling journey to Stevenson’s Pacific island paradise by his desire to stay near his frail, elderly mother – feelings he later explores intensely in Peter Pan – and had to content himself with merely writing 3,000-word letters to his beloved friend.

Later, he recounts Stevenson’s whimsical directions to the island of Samoa (“you take the boat at San Francisco, and then my place is second to the left”), which seem to echo Peter Pan’s famous directions for the island of Neverland: “Second to the right and straight on till morning.”

While many of Stevenson’s letters to Barrie appeared in print soon after Stevenson’s death in 1894 and the rest were published over the course of the 20th century, Barrie’s side of the correspondence has, until now, remained unpublished.

Dr Michael Shaw, a lecturer in Scottish literature at the University of Stirling, came across the letters while researching a box of correspondence at Beinecke Library in Yale University. The letters had been acquired by the collector Edwin J.Beinecke in the 1950s and were catalogued and listed in the library archive. But throughout the last century key Barrie biographers have speculated about their whereabouts and existence. Some wrote that they believed the letters were “lost”. Barrie himself wondered whether his side of the correspondence had been thrown away. In a notebook entry from 1922 he wrote “odd that with so much of R.L.S. none of the letters to him published. Perhaps not kept”.

“When I first saw them, I didn’t realise that these were “lost” letters,” Shaw told the Observer. “I just assumed that they had been published and I didn’t know about them. I was judging myself, thinking I really should have read these.”

It was only when he tried to buy a book of the correspondence and researched why it was not available that he realised what he had unearthed.

In Shaw’s forthcoming book, A Friendship in Letters, Barrie and Stevenson’s letters to each other are published together for the first time. “What’s revealed in these letters – and it took me a while to discover the full extent of this – is the influence that both Stevenson and the correspondence have on Barrie,” said Shaw. “In reading over Barrie’s works, I started to see allusions to the letters and to Stevenson that I hadn’t noticed before.”

Barrie, he said, loves to play games with his writing and unsettle the line between art and reality. “And I could see how he was doing that with the correspondence. He’s incorporating aspects of the correspondence into his own works, into his poetry and novels, and their friendship is also inspiring his works.”

He tries to keep his bond with Stevenson alive in other ways, too. Odd little phrases Stevenson used in his letters creep into Barrie’s stories, and Peter Pan was placed in the same imaginary world as Treasure Island. Long John Silver (who is known by his aliases of Barbecue and Sea-Cook in Neverland) is afraid of only one man, readers are told: Captain Hook.

“As a literary critic, I’m trained to be sceptical of biography coming into literary text,” said Shaw, “but the more I re-read Peter Pan, the more potential references I found not just to Treasure Island but to Stevenson, Samoa and their life.”

Barrie has a real desire to incorporate Stevenson and his affection for Stevenson in his works, he believes. “I think what Barrie is saying is: if I can never meet Stevenson, because he has unfortunately died, then I want to create the opportunity for our characters to meet.

“I think he liked that idea that they could occupy the same world, and could potentially bump into each other.”