Portrait from library collection featured in lavish Pulitzer Prize–winning opera “Omar”

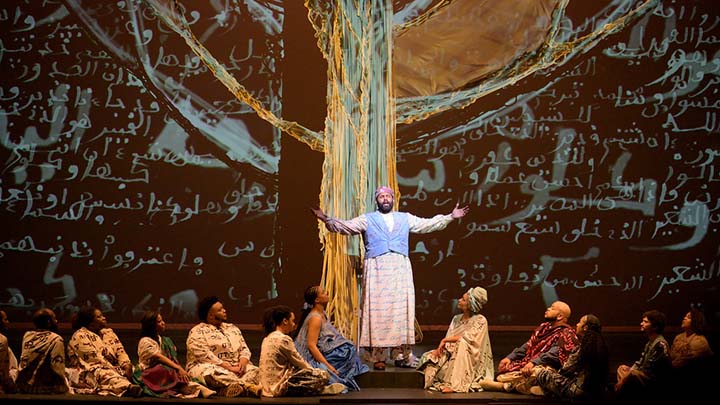

As the Boston Lyric Opera opened its performance of Omar, audience member Roberta Dougherty, librarian of Middle East Studies, was delighted to see a larger-than-life projection of a familiar face. A portrait of Omar ibn Said, the subject of the opera, was projected onto the drawn curtain, nearly spilling onto the proscenium. The animated figure appeared to blink, as if just waking up.

Dougherty knew the portrait well. The original image is currently on display in the Beinecke Library’s exhibit Revisiting the Past, Imagining the Future, which Dougherty had co-curated with colleagues throughout the library. The circa 1850 ambrotype (a positive image on glass) is from the library’s Randolph Linsly Simpson African American Collection, James Weldon Memorial Collection. It is one of only three known portraits of the man, who is identified in a handwritten caption as “Uncle Moreau, a slave of great notoriety.”

The library’s portrait of Omar was projected in the same way again at the end of the performance. The image also recurs in the extensive publicity and press coverage for the acclaimed production.

Omar ibn Said

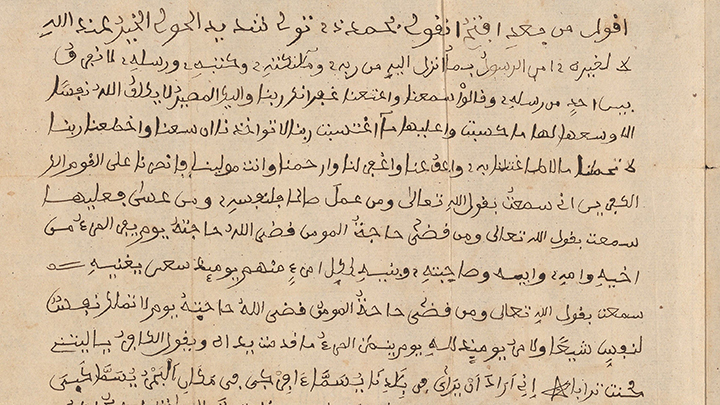

Omar ibn Said was a Muslim scholar born in present-day Senegal, enslaved there, and transported to South Carolina, in 1807. After fleeing his enslaver on foot, he was imprisoned in North Carolina. He covered the walls of his cell with verses from the Quran, written in charcoal, revealing himself as an educated man. Omar eventually was purchased again, by James Owen, and lived the rest of his life in North Carolina as an enslaved person, until his death in 1863.

The opera, which premiered at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina in 2022, is based on Omar’s 1831 memoir—the only known surviving Arabic-language slave narrative written in the United States.

In 2019, the original manuscript of Omar’s memoir was added to the collection of the Library of Congress.

Printed and digital English-language translations are in Yale Library’s collection. Native Arabic speaker Ala Alryyes worked on the translation while a faculty member in Yale’s English and Comparative Literature department.

The writing

To help tell Omar’s story, the performers’ costumes, the backdrops, and the sets are profusely decorated with reproductions of Arabic script. The Beinecke exhibit also includes a letter that Omar wrote to his enslaver’s brother, John Owen, a future governor of North Carolina. “Although I couldn’t be sure that any of the writing that appeared in the production was taken from the one letter we have at the library,” Dougherty said, “completely coincidentally I chose both the ambrotype and the letter for the Beinecke exhibit before I knew anything about the opera.”

Former faculty member Edward Ball—author of the National Book Award winner Slaves in the Family—reviewed the opera for The New York Review of Books. In the process, he visited Beinecke to view Omar’s letter. “His calligraphy is luscious,” Ball writes, “and I realized that the production had made the superb decision to simply transfer Omar’s actual handwriting onto the costumes and sets, until the written texts spread like an imprint over nearly everything onstage.”

Yale not only contributed to the performance through the lending of Omar’s image. The performers’ costumes were designed by April Monique Hickman, who earned her MFA in costume design from Yale School of Drama in 2020 and is now on the faculty of the theater department at Wesleyan University.

On view

The opera’s two composers—Rhiannon Giddens, a Grammy Award winner and 2017 recipient of a MacArthur Genius Grant, and Emmy- and Grammy-nominated Michael Abels—have just received the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Music for the score. The production, which after Spoleto was staged in North Carolina and Los Angeles, will be performed in San Francisco in November and in Chicago in an upcoming season.

View Omar’s portrait and letter in the exhibition Revisiting the Past, Imagining the Future, at the Beinecke Library through July 9. Watch the video of Dougherty’s Mondays at Beinecke presentation about Omar ibn Said’s portrait and letter to John Owen.

—Deborah Cannarella

Images: Jamez McCorkle (center) and cast members of Omar, photo by Leigh Webber, courtesy of Spoleto Festival USA; half-length formal portrait of “Uncle Moreau” (Omar ibn Said), detail, ca. 1850, Randolph Linsley Simpson African American Collection, James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection; detail of letter in Arabic Maghribi script, containing texts from the Quran and treatises on Arabic grammar, from Omar ibn Said to John Owen, Raleigh, North Carolina, ca. 1819