Culture & Community | Film | Arts & Culture | New Haven Museum | Yale University | History | Arts & Anti-racism

Tubyez Cropper Wednesday night. Lucy Gellman Photo.

The year is 2023. Just beyond East and Water Streets, the nation’s first Historically Black College is gearing up for its 192nd anniversary. Balloons bob in the breeze outside. Buildings reach into the blue New Haven sky. Gulls cry and cackle above the water, and sound like they are laughing. All day, the nation’s most prominent Black scholars file in and out of the campus buildings, holding a history that is nearly two centuries old.

Except, their path to that day never happened. The year is 2023, and the space is just an ocean of asphalt and road, with a labyrinth of highway winding above. It didn’t have to be this way.

That message is at the heart of What Could Have Been, a 2022 documentary from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library about the nation’s first proposed HBCU in 1830s New Haven. Directed by Tubyez Cropper and written by Cropper and Michael Morand, it tells the story of the proposal and fight for the first Black College, an overwhelming white vote against it, and the ramifications for New Haven, for Connecticut, and the country.

Wednesday night, over 100 New Haveners gathered at the New Haven Museum for a screening of the film, followed by a short question-and-answer period with Cropper. In a clean 25 minutes, the film is both a testament to the weight of history, and the need to tell it in full. It has the right storytellers at the helm: Cropper and Morand both work in community engagement at the Beinecke, and share a love for text, original sources, and history.

“Primary sources allow us to relive, not ignore,” said Cropper, who grew up in New Haven and started at the Beinecke as a New Haven Promise intern in 2018, during his junior year at Franklin & Marshall College. “We have a duty, in us here as history lovers or history enthusiasts, to make sure that everyone knows that this happened.”

“I won’t say names of states and governments, but certain parts of the nation are trying to hide it,” he continued. “[They] are trying to get rid of it. Are trying to make sure students never learn about it again. And these sources … It matters. It makes it that much more real. Seeing is believing, and primary history allows us to see, step into, and relive. So that we can engage the past in the present, for the future.”

Morand: "The fact that the story gets forgotten is part of the story of the film."

Wednesday, Morand stressed that several New Haveners paved the way for the film, which came out in April 2022. In 1991, now-retired Hillhouse High School librarian Robert Gibson wrote an article on the college during his graduate studies at Southern Connecticut State University. Ten years after that, the Amistad Committee discussed it in their report "Yale, Slavery & Abolition," which challenged Yale's whitewashed history of activism, equity and progress. Then two and a half years ago, the Yale & Slaver Research Project was born as an initiative of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition.

The last was central in making the film and spreading its message, Morand said. Since the premiere last year, it has gotten over 13,000 views. He noted the importance of becoming an ambassador for the information, to both tell people about the film, and carry the story further than any one given screen.

"The fact that the story gets forgotten is part of the story of the film and part of what we all need to grapple with," Morand said Wednesday. "The work that they [Yale] are doing now is very important, but we need to be cognizant that it's coming when it's coming, building on extraordinary work that precedes it."

From the opening shot, that message is evident, and carries right into the present. In the first moments of the film—expertly narrated by Dixwell Avenue Congregational United Church of Christ (Dixwell UCC) Historian Charles Warner, Jr.—viewers situate themselves in 1830 New Haven, then the co-capital of Connecticut with Hartford. At the time, New Haven laid claim to close to 11,000 residents, including new immigrants from Europe and the U.K. drawn by the promise of trade and education. Yale, which admitted white, Protestant men, was still the largest school in the U.S. with close to 500 students.

While the majority of that population was white, 1830s New Haven also had close to 600 free Black residents, and four recorded enslaved residents (Connecticut did not abolish slavery until 1848; the last known sale of enslaved Black people took place on the New Haven Green in 1825). Because of the racial and economic barriers that white residents created, Black people “were organizing churches and building community institutions, creating their own spaces of liberation,” explains Warner in the film.

Enter a meeting of Black people—including New Havener Scipio Augustus—“from throughout the antebellum North” at Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia in 1830. In what is now seen as the birth of the abolition movement, Augustus listened to Robert Allen, the first bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Back in New Haven, he organized with both Black men —John Creed and J.L. Cross specifically—and with white abolitionist Pastor Simeon Jocelyn, who ministered at what was then the Temple Street Congregational Church.

A still from the documentary.

Those relationships are the building blocks of the college. In 1831, Jocelyn contacted William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of The Liberator, with the earliest inklings of a Black college in New Haven, nestled where Interstates 91 and 95 now meet beneath the wide New Haven sky. From the letter, it’s clear that Jocelyn was a white accomplice before the concept ever existed: he had worked with the Black Rev. Peter Williams before going forward with the idea. Jocelyn wrote at the time:

This would connect mechanic arts and some degree of agriculture and horticulture, as well as be connected with many useful pursuits, and with the advantages of domestic and social life, as would prepare the young men for active life, and to aid their brethren in other places, in all those things, which make men happy, and which give them as individuals and as communities influence in the world.

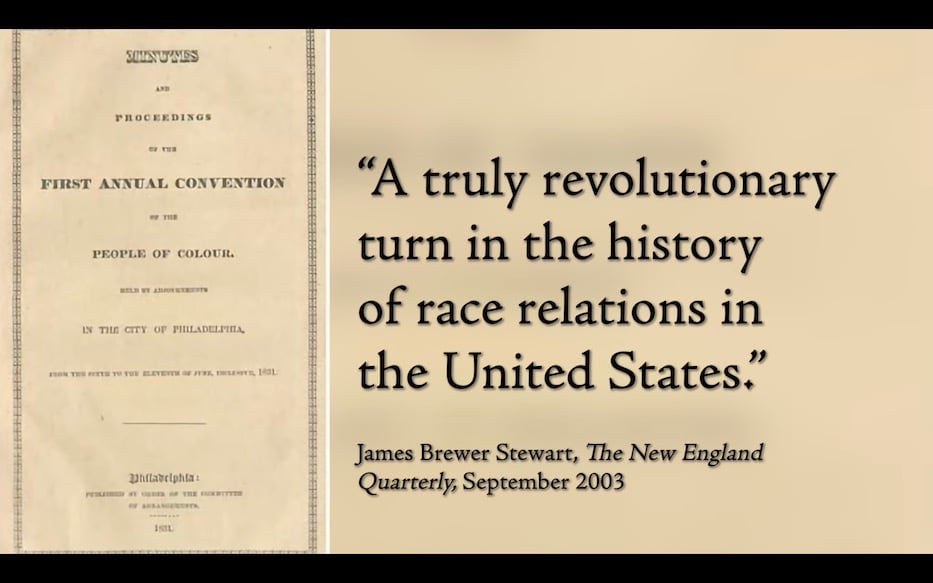

Other accomplices emerged from the woodwork, as they still do today. There was Arthur Tappan, who offered up an initial investment of $1,000 in seed money for the college. There was Garrison, who backed the plan, spoke about it in New Haven, and circulated the news through the abolitionist press. Later, there was John Warner Barber, who both voted in favor of the college, and had the sense to preserve his documents for posterity. In June 1831, the first three brought the plan to the first annual Convention of the People of Color, held in Philadelphia.

After getting sign off from the Convention’s delegates—including a plan for a majority-Black board—they returned to New Haven with excitement around the college. By the second half of 1831, their goal was to raise $20,000—$10,000 each among white and Black donors—and begin the project. News of the college had begun to spread, particularly through abolitionist strongholds in New York and Pennsylvania.

But by September of that year—when Jocelyn gave an address that “no doubt” mentioned the college, according to the film—supporters of the plan began to meet resistance from white residents of the city. New Haven newspapers were publishing accounts of Nat Turner’s Rebellion, in which over four dozen white people were killed in August 1831. On Sept. 8, property owning white male Yale grad-turned-Mayor Dennis Kimberly called a meeting at the city’s State House to vote on the college.

Only white, male property owners could attend and vote. As Warner’s voice boomed over the room, a few attendees Tsk tsked and mmmd back at the screen to show their disapproval.

It was a blowout. In the sticky, still-warm 3,000 square foot space, hundreds of men squeezed shoulder to shoulder to watch—and vote in—the proceedings. The final vote was 700 opposed to the plan, and only four in support. Among those who spoke out most passionately against the college were Isaac Townsend, Nathan Smith, Ralph Ingersoll, and David Daggett—all men after whom streets, buildings, and history rooms are now named.

They didn’t stop there. In a two-part resolution against the college, a committee appointed by the mayor went further than simply voting the measure down. Members, of which there were 10, noted that the decision was in part to defend the practice of chattel slavery in the U.S., calling the foundation of such a college “‘an unwarrantable and dangerous interference with the internal concerns of other States.”

The committee went further, claiming that a Black college posed a direct and real threat to Yale, and to fellow institutions of education that existed in New Haven. Citing the sons of Southern planters —in other words, the children of slave owners—as particularly valuable to Yale’s student body, the committee claimed “there is no other town or city that would suffer as much if such a college, a Black college, were built.”

It would be a century later that the university, in an attempt to woo more Southern students, would name a college after white supremacist John C. Calhoun. The first HBCU, meanwhile, came six years later, when Cheyney University opened in Cheyney, Pennsylvania in February 1837.

The aftershocks of the vote continued for weeks and then years—and not just in New Haven. In fall 1831, Tappan’s Connecticut home was burned to the ground, as was the home of a free Black man who was not named in the press. Black people became the subjects of verbal and physical harassment across the city. Southerners from Virginia to Louisiana to Georgia celebrated the college’s defeat, their white supremacist revelry and glee memorialized in the press.

In Connecticut and across the country, the vote became a springboard for other measures meant to curb Black education, and with it basic and essential human rights. In 1833, the Connecticut State Legislature passed the state's “Black Law,” barring the education of Black people in the state, and shutting down a school for Black women that Prudence Crandall ran in the town of Canterbury. That building is still standing, now as a historic state landmark.

As Warner explains in the film, the Supreme Court of the United States later drew on the state's ruling in their Dred Scott v. Sandford decision. In other words, the vote supported for years, and far beyond Connecticut, the notion that Black people were property, and less than human.

Almost two centuries later, the film sticks. Long after the credits have rolled, What Could Have Been pushes a viewer to think about the violent and enduring effects of de facto segregation and anti-Black racism on the city, from its educational landscape to still-buried or little told Black histories. For every Edward Bouchet, William Lanson, and Sarah Boone who New Haveners now know, how many hundreds of names are missing?

And how many were erased from the historical record in an act of white violence? The New Haven Museum sits on Whitney Avenue, a wide street named after the man who extended chattel slavery by decades with the invention of the cotton gin. Downstairs, there is an Ingersoll Room, where the Federalist furniture sits quietly, as if it’s simply waiting for its owners to return. One realizes that it might have been the Tappan Room, had history been kinder.

In July 2021—almost exactly 190 years after the college vote—a new mostly-white mayoral appointed committee voted to replace one monument to colonialism and white nostalgia with another, despite calls from the community to honor William Lanson in what is now Wooster Square. Last Juneteenth, New Haven cops paralyzed Randy Cox, a Black man, after refusing to listen to him as he insisted something was wrong. It played into centuries-old, medically false stereotypes that left him fighting for his life.

Is this where New Haven is? On the lip of budget season and a mayoral election, can it do better? In another 192 years, what will a film say about this moment, and who chose to be on the right side of history?

Cropper, an Amistad Achievement First High School grad who has worked at the Beinecke since early 2020, said he is still optimistic for the future. Growing up “everywhere” in New Haven—first in Beaver Hills, and then across the city—he saw firsthand that New Haven was a city in contrasts. He never visited the Beinecke, despite graduating high school just down the block at Woolsey Hall. When he got into Yale his senior year of high school, he opted to go to Franklin & Marshall instead.

“I knew the doors it could open for me, but it didn’t feel right,” he said Wednesday, in a conversation after the documentary. “New Haven natives are told the real history of Yale.”

And yet, it's now part of his New Haven story. In college, Cropper was studying business when he fell unexpectedly in love with film production, then history. After interning at the Beinecke in 2018, he returned three years ago to work under Morand, and help tell stories of New Haven and America’s past. He called Yale's recent work into its past both a reclamation and an overdue reckoning.

“History is a privilege,” he said. “And everyone has a right to that privilege. I feel optimism that people will fight back. I believe that if people want to find the truth, they’re gonna find it.”

Waiting for his chance to talk to the young filmmaker, Gibson said he was moved by the film. As a graduate student at Southern three decades ago, he gravitated towards the story because it was so undertold, and so central to New Haven. He remembered feeling impressed—he still is—that Jocelyn and his white colleagues had the sense to talk to Black community members before assuming they knew what was right.

Watch What Could Have Been above, or visit the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library for more historical goodies.