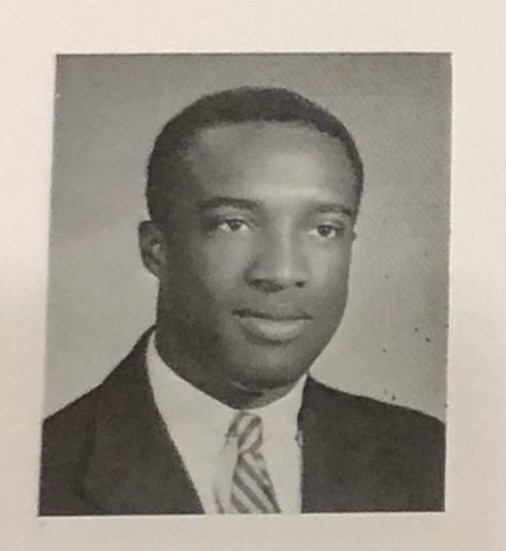

During Martin Luther King Jr. week and in advance of events, activities, and exhibits being organized for Black History Month, Yale saw the return of one of its alumni: Brigadier General Enoch “Woody” Woodhouse II ’52, a World War II veteran who, having served with the 332nd Fighter Group, the highly decorated WWII military unit comprised entirely of African American pilots and other personnel, is one of the last surviving members of the Tuskegee Airmen.

Having attended his 70th reunion two years ago, Woodhouse was delighted to be invited back to campus, accompanied by his wife, Stella, and shortly after turning 97 years old. Throughout his two-day visit, which included a packed schedule of appointments, meetings, and speaking engagements, Woodhouse made clear his deep affection for his alma mater.

“I love Yale,” he said, noting his steadfast optimism for its capacity to educate the leaders of tomorrow and contribute to the world through scholarship, research, and practice.

During his visit, Woodhouse captivated alumni, faculty, staff, and students with insights and anecdotes drawn from an extraordinary life grounded in faith, learning, perseverance, and service.

Born a few years before the Great Depression, he was the son of Rev. Enoch Odell Woodhouse and Gertrude Tyler Woodhouse—and proud of his family background coming from “two generations of black preachers.” He grew up in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston and attended local public schools (his diligence as a student earned him the nickname ‘The Little Professor’), including The English High School, one of the first public high schools in the United States.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, his mother urged him to serve his country and do his part in the war effort. Underaged at the time, he had to wait until turning 17 before he could enlist in the U.S. Army, eventually serving in its aviation component, the U.S. Army Air Corps, precursor of the U.S. Air Force. His brother also answered the call to duty, becoming one of the first African Americans to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps.

In 1946, at the age of 19, Woodhouse was commissioned as an officer (second lieutenant) and assigned to the 332nd Fighter Group, where he became the unit’s paymaster and finance officer. He remained on active duty until his discharge in 1949 and continued to serve in uniform in the Air Force Reserve until his retirement in 1972 as a lieutenant colonel. In 2022, the governor of Massachusetts appointed him to the state militia with the rank of brigadier general.

As someone who served when the U.S. military was segregated (until 1948), Woodhouse experienced his share of discrimination and unequal treatment. He recounted an occasion when he was ejected from a train by a white conductor while traveling in uniform for training—he was later informed by a black porter that black people were not allowed to ride on that train.

When asked during a campus talk for his thoughts on being a member of ‘The Greatest Generation,’ Woodhouse was quick to point out that he did not consider himself or other Americans of that generation to be special—they were simply unified and united – regardless of race, religion, or socioeconomic status – by a shared sense of duty during a time of war.

“We were ‘great’ because we served,” he said. “And we were proud to do it.”

His wartime experiences, military service, and maturity would serve him well when he landed in New Haven as a Yale undergraduate with the Class of 1952.

At Yale, Woodhouse was a member of Berkeley College, active with the Political Union, worked as a bursary student at Sterling Memorial Library, spent his junior year abroad in France at the Sorbonne (University of Paris), and majored in French and psychology.

He also encountered ostracism, intolerance, and isolation as a black student on campus. Within days of arrival, he received threatening notes with racial epithets slipped under his dorm room door, likely perpetrated by fellow students who not only lived in the same building but in the same entryway as him. No one wanted to room with him—he joked a benefit of this was that he got his own private suite. He was ignored in classes and during meals in the dining hall.

Despite these and other negative experiences, Woodhouse doesn’t consider himself a ‘victim’ and he would be the first to correct anyone who would refer to him as one.

“What do you do? You suck it up and keep moving,” he said. “It’s not easy but you have to do it.”

During a campus talk, Woodhouse shared with students the mindset that helped him overcome the challenges he faced as an undergrad, something that linked Yalies of the past to current generations.

“The main reason we were here, and to be here, was to be excellent,” he said. “There is no substitute for excellence.”

Woodhouse reminded students they were at Yale to acquire a top-notch education and learn to use their talents for the betterment of society and the world. Accordingly, he urged them to take their studies seriously and make the most of their time on campus.

“Use your time, use your effort well, and connect with others,” he said, adding they should always be stretching themselves. “Every day should be a new day where you do something different.”

Woodhouse also encouraged students, whenever facing obstacles and difficulties in life, to not take the easy path, no matter how tempting or expedient.

“Don’t beg for a place at the table,” he said. “Earn it.”

After completing his bachelor's degree, Woodhouse remained in New Haven and attended Yale Law School, eventually earning his law degree from Boston University in 1955.

For the next more than 40 years, he embarked on a varied career path that included working as an attorney in private practice, with the State Department, and with the City of Boston; serving in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps, the military justice branch of the U.S. Armed Forces; and teaching in high school.

Woodhouse was also an active alumni volunteer, becoming one of the first members of the then-Association of Yale Alumni (now Yale Alumni Association) board of governors.

Upon his retirement, he traveled across the country as a sought-after speaker at events honoring veterans and continued his longtime advocacy for veterans and military families.

Over the years he has received many awards and honors. This included, in 2007, along with other surviving Tuskegee Airmen, the Congressional Gold Medal from President George W. Bush ’68. In 2022, two murals of Woodhouse were unveiled at Boston Logan International Airport and in 2023, the Boston City Council designated a major section in the Back Bay neighborhood in recognition of him.

Woodhouse mentioned that, later this year, he was looking forward to representing Yale at the 80th anniversary of D-Day in Normandy.

Throughout his visit and his interactions with members of the Yale community, Woodhouse left an indelible impression.

Ceily Addison, a Yale College sophomore and enrolled Air Force ROTC cadet who moderated a talk with Woodhouse, shared how inspired she was to meet him.

“I take great pride in leaders like General Woodhouse who have risen up to defend freedom and create a legacy of advancement for future generations to continue,” she said. “As the daughter of a black veteran, I have always respected that sacrifice, especially with the heavy challenges of racism and slave descendancy.”

Addison, whose father was a career U.S. Air Force officer who retired as a lieutenant colonel, described her commitment to continue the legacy of military service and follow in the footsteps of veterans like her father and Woodhouse.

“My decision to join the military is rooted in service to America and to mankind through the greatness that I truly believe this country can support,” she said, adding that Woodhouse’s message about excellence resonated strongly with her. “I will not forget that there is no substitute for excellence, and that it is my duty to apply it beyond expectations.”

According to Timeica Bethel-Macaire ’11, assistant dean of Yale College and director of the Afro-American Cultural Center at Yale, which hosted Woodhouse as a guest speaker, exposing students to alumni like him constituted an important component of their education.

“Welcoming alumni like General Woodhouse back to campus allows students to engage with people who have sat in their seats and gone on to have a tremendous impact,” she said. “It’s a rare experience to be in such an intimate setting with a leader of his stature.”

Meeting Woodhouse also meant a lot to her personally.

“As a Black person, it was an honor to meet an elder of my community,” she said, adding how much she appreciated Woodhouse’s support of the Afro-American Cultural Center. “I was most pleased when someone asked his thoughts on the founding and existence of The House, he said, ‘I’m proud and pleased to see a dream realized.’”

Michael Morand ’87, ’93 MDiv, director for community engagement at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, who arranged a special visit of the Library for Woodhouse, including a meeting with staff members, remarked that alumni like Woodhouse are a wealth of knowledge, wisdom, and experience that informs the greater narrative of Yale and, therefore, is worthy of documentation, preservation, and dissemination.

“We have so much more to learn about the full story of Yale,” he said. “People like General Woodhouse bless us all when they share their stories—it’s a privilege to learn these stories and a solemn duty to make sure they are more broadly known.”

Morand added that Woodhouse and others who have lived through history are not only a link to the past, but also bellwethers for the future.

“He is one of the greatest living memory keepers of Yale,” he said. “My colleagues and I were keen to learn from his living legacy more about what Yale has been, and what it can be.”

These sentiments were echoed by Tubyez Cropper, community engagement program manager at the Library, who led a private tour for Woodhouse that included a sneak preview of an exhibit featuring original scrapbooks from American abolitionist and orator, Frederick Douglass.

“His words were breathtaking and inspiring—it helps to hear such historical narratives from living icons,” he said, noting how much he and other Library employees benefited from hearing about Woodhouse’s life experiences, including his stint as a student worker at Sterling Memorial Library. “Our staff certainly gained perspective.”

Cropper added that listening to those who have lived history can offer invaluable insights and lessons about possibilities for tomorrow.

“History is truly happening every day,” he said. “We must always look to the past to forge a more prosperous future.”

Woodhouse’s visit also included a stop at the Yale Jackson School of Global Affairs, where he was a guest speaker for a seminar course, focusing on field operations in international relations, taught by Matt Trevithick ’20 MAS, a lecturer at the School, who was thrilled to open the first session of his course with Woodhouse as a speaker.

“Our class is a practitioner’s class inside a practitioner’s school, so what better way to start a course than to bring a Tuskegee Airman to explain to us what serving in World War II was like, and how the world fit together after that,” he said. “I hope my students reveled in being able to engage with a remarkable individual who has lived and experienced all of the history our course builds on.”

Trevithick, who before Yale spent a decade living and working across the Middle East, Central Asia, and North Africa, emphasized the importance of capitalizing on the living memories and experiences of those like Woodhouse to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

“We need to keep history alive and transmitted down the generations, not just the events but the lessons humanity has learned from those events,” he said. “The structures and systems that defined Woodhouse’s life are changing, and while that comes with new opportunities, it also comes with the increased risk of repeating mistakes we've made because we've forgotten the lessons.”

In addition to the historical lessons, Trevithick shared how much he gained personally listening to Woodhouse.

“He’s taught me the importance of having a good sense of humor, and maintaining that through it all,” he said. “Here is a man who has overcome one obstacle after the next – things that would probably make a lot of people bitter and resentful – and there he is, 97 years young, cracking jokes, laughing easily, and making students smile. It’s a beautiful thing.”

As the last stop of his campus visit, Woodhouse attended a luncheon in his honor hosted by Yale President Peter Salovey ’86 PhD and his wife, Marta Moret ’84 MPH, at the President’s House, where guests were able to meet and reconnect with him.

Among those in attendance was Tom Opladen ’66, founder and president emeritus of the Yale Veterans Association, and a U.S. Navy veteran.

“We should be impressed with his optimism about America and its future, particularly from a person who has successfully fought and won so many battles of both a national and personal nature,” he said. “I was also impressed with his desire to communicate his ideas to others.”

Having first met Woodhouse two years ago at an alumni reception for veterans during the Yale College reunions, Opladen was delighted to see him again and expressed his admiration for both him and his family for the grace, dignity, and honor in which they lived their lives, despite the intolerance and adversity that they encountered.

“The intense patriotism displayed by Woodhouse and his family despite the racial prejudice they experienced was truly memorable,” he said. “Our country needs more Woodhouses.”

Meeting Woodhouse for the first time, Rod Lowe, senior associate director of major gifts at Yale Divinity School, and a U.S. Army veteran and co-chair of the Yale Veterans Network, opined that Woodhouse, from his words to his deeds, embodied the highest values and traditions of his alma mater.

“It was truly an honor to be in the presence of this living legend, whose life of service to God, Country, and Yale continues to serve as an example to every veteran,” he said.

Lowe was likewise impressed by his energy, enthusiasm, and hopefulness for the future.

“I am inspired by his resiliency and his optimism about the future of Yale and the nation,” he said, adding that Woodhouse’s life lessons and example were not lost on him. “My biggest takeaway from meeting him is to never forget to pay it forward and never lose hope in the humanity of everyone.”

Before Woodhouse and his wife boarded their vehicle to return to Boston, President Salovey, in his parting words at the farewell luncheon, shared with him the deep sentiment that was on the minds of everyone with whom he met and connected during his visit.

“You are a wonderful hero that we can all admire.”