🎙️ Voice is AI-generated. Inconsistencies may occur.

Zelda Fitzgerald once gauged a publisher's interest in creating a collection filled with the striking paper dolls she made for her daughter, but the book she imagined never materialized.

More than 70 years after Zelda's death, that imagining has now come to life in The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald, a collection pulled together by Zelda's granddaughter, Eleanor Lanahan. Scribner is publishing the book on November 22.

During a recent interview with Newsweek, Lanahan said she first came across the paper dolls while exploring her mother's attic as a child.

"I'm a true fan of these dolls," Lanahan said. "I had always wanted to do a book of just them."

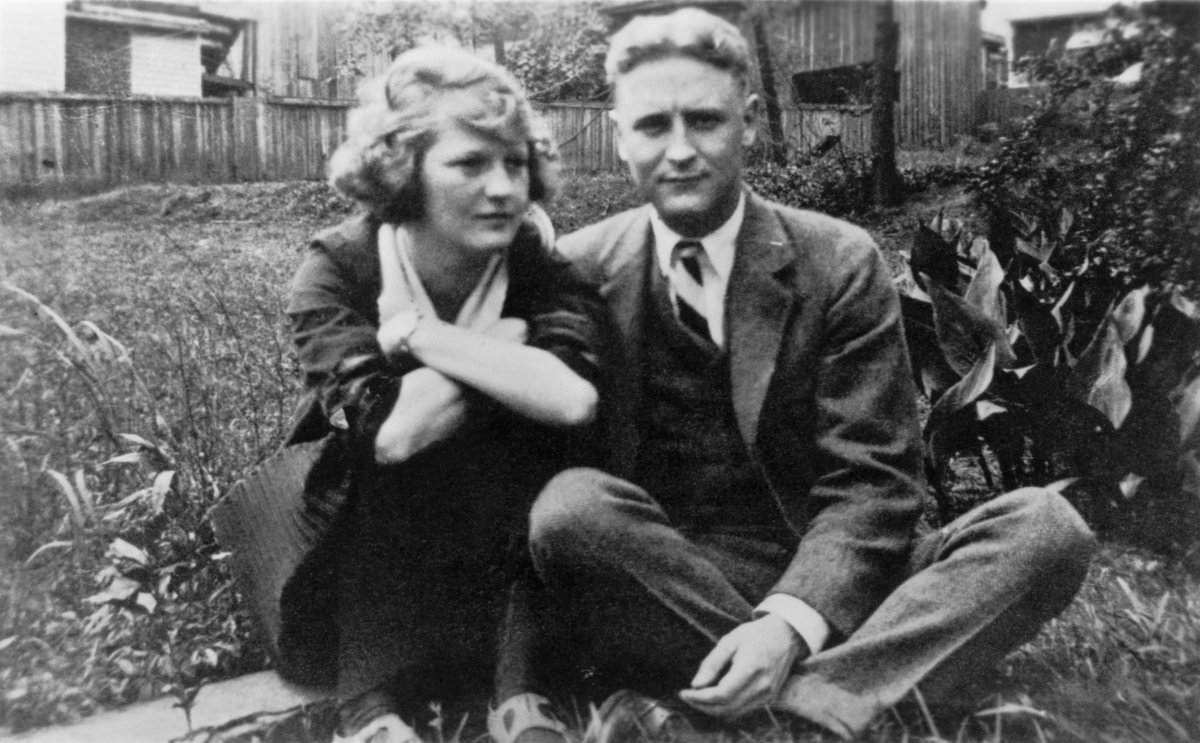

Zelda's name became linked to the Jazz Age as her husband, F. Scott Fitzgerald, published modern classics like The Beautiful and Damned and The Great Gatsby in the 1920s. But public curiosity about Zelda as a person and artist was not immediate.

"The interest in Zelda has grown, I'd say, in the past 10 years. It's been more about her—and people are not just thinking of her as having an illness," Lanahan said, referring to the time Zelda spent in mental health facilities. Instead, Lanahan said people are "realizing she was extremely creative."

Zelda was a published writer and author, a playwright and a painter. She was also a dancer, whose time at a Paris ballet school Lanahan believes inspired some of the paper doll costumes Zelda made.

Images of the dolls are lined up side by side on the cover of The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald. Inside, the book begins with a brief overview of Zelda's life before presenting page after page of the colorful costumes and dolls, many of which Lanahan writes are about 12 inches tall. The dolls demonstrate serious studies of the human form, while the costume choices add splashes of color and style.

"There's something very related to dance, the way they are so muscley and the way they are so airborne and dramatic, really balletic," Lanahan said of the dolls.

Zelda used gouache, a kind of watercolor, while making the dolls, which Lanahan said helps them retain vibrancy. Lanahan notes in the book that some of the costumes were made using materials such as paper foil, crepe paper and fabric. She also quotes her mother, Scottie Fitzgerald, as recalling one of her paper dolls having an outfit with "ruffles of real lace cut from a Belgian handkerchief."

Some of the paper dolls are depictions of the Fitzgerald family. Others portray fairytale characters, like Little Red Riding Hood and Goldilocks. There are even dolls inspired by members of French King Louis XIV's court, though Lanahan writes that Zelda didn't identify who each of those dolls were based on.

"It was fun to look up various court members and guess who they were, and suddenly they just really sprang to life for me," Lanahan said.

Lanahan writes that Zelda first began making the paper dolls after moving to Delaware in late 1926 and continued through the arrival of Zelda's first grandchild in 1946. But in the decades after Zelda's death in 1948, Lanahan said the paper dolls became somewhat "scattered"—and she still isn't sure she knows where they all are.

"I think there are probably some I haven't found," she said. "But of the ones that I found, I put them in [the book]."

Lanahan and her family have inherited many of the paper dolls. A few that Zelda first created for her daughter were "destroyed by play," Lanahan said, and pieces are missing from others. Some were sold at auction or acquired by academic collections, such as the set of dolls at Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. A curator at the Yale library told Newsweek the dolls in its collection, which Lanahan included in her book, were acquired at auction in 2008.

Though Zelda began making the dolls as playthings for her daughter, she explored the possibility of publishing a collection of them in 1941. Lanahan quotes a letter Zelda wrote in which she pitched the idea to Maxwell Perkins, her husband's agent.

"There's no record of his replying to that at all," Lanahan said.

Zelda explored other ways to showcase her paper dolls that same year, Lanahan says in the book, and got them placed in a children's room exhibit at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts. In the mid-1970s, another exhibit of Zelda's paper dolls was coordinated at the Montgomery museum with help from her daughter. Some paper dolls "disappeared" after that exhibit, Lanahan said, with a few showing up at auction years later.

Lanahan said her mother saved most of the paper dolls Zelda made, as well as her other artwork. When Lanahan first found the dolls in her mother's attic, she said they were in "ratty old portfolios" and "just kind of tossed with their costumes."

"I knew it was a treasure, and nobody said 'don't touch,' so I just, when I was up there, I would go through them," Lanahan said. She recalled being "scared of [Zelda's] characters" and paintings as a child, "especially the animals," which often danced on hind legs. "I didn't know what to make of them. I still loved them, because of the colors and stage sets."

Lanahan said she made her own paper dolls with her mother as a child, "but they weren't anywhere near as beautiful as what Zelda did."

Years later, after the collection became scattered, Lanahan said she kept an eye out for any dolls that popped up at auction and tried keeping track of who had them. When interest in Zelda began rising—Lanahan cited the Amazon TV series Z: The Beginning of Everything as one example—she decided to revisit the book idea her grandmother pitched decades earlier.

"There was just such an untold story there for me," Lanahan said, later adding, "I think the time was right."

Lanahan said she is hopeful that interest in Zelda and Zelda's art will continue to grow. She describes Zelda in the book as a person always open to new artistic interests, excelling in many.

"What she wanted was artistic freedom," Lanahan said. "And I think to a huge extent she had it."

Lanahan said she "appreciates" Zelda's "most unusual use of language and metaphor."

"I don't think she put together an ordinary sentence, really," Lanahan said. "I think she had a mischievous sense of humor, and liked to toy with ideas, and was always making something. You can just feel it. I mean, her dolls are not like anyone else's dolls."

Lanahan said she hopes The Paper Dolls of Zelda Fitzgerald "inspires people" and that readers "have fun with it."

"I don't imagine that it's going to bring paper dolls back as the number one plaything," she said. "But it may inspire some harkening back to childhood. It's one of those things you can do with your own children, so it's got a good application, if people are inspired by it at all."

The book brings a sense of relief for Lanahan by putting images of all the paper dolls she knows about in one place. It also brings a close to the inquiry Zelda made about publishing the collection nearly 82 years ago.

"It's something she wanted. I love that feeling," Lanahan said. "I feel I owe it to her."

About the writer

Meghan Roos is a Newsweek reporter based in Southern California. Her focus is reporting on breaking news for Newsweek's Live ... Read more