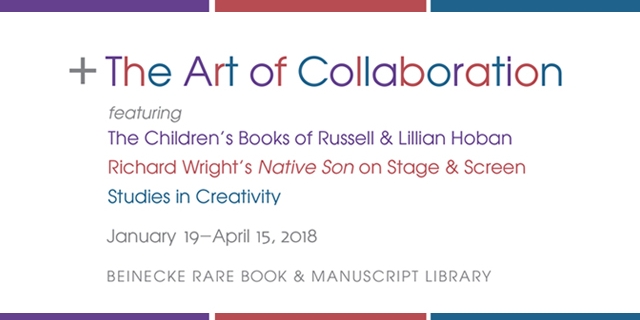

+ The Art of Collaboration

+ The Art of Collaboration

+ The Art of Collaboration explores the excitement and power of separate elements combining to make things that are new, beautiful, strange, and memorable. Drawn from the Betsy Beinecke Shirley Collection of American Children’s Literature, the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters, and the Yale Collection of American Literature, this exhibition considers exemplary works and the archival stories of their making, revealing the creative—and sometimes destructive—tensions that are parts of artistic collaboration. The works on view—including plays, children’s books, novels, performance artworks, films, photographs, and more—demonstrate that collaboration itself is an art form. “+ The Art of Collaboration” comprises three discrete exhibitions, each installed in a separate section of the library’s exhibition space. Cases on the ground floor consider the much-beloved work of a husband-and-wife team in “The Children’s Books of Russell and Lillian Hoban.” A story of the complexity of collaborative adaptation is explored in the curved cases at the top of each staircase in “Richard Wright’s Native Son on Stage and Screen.” The jewel-box vitrines on the mezzanine feature 18 instances of American literary and artistic collaboration spanning more than 100 years in “Studies in Creativity.”

Melissa Barton, Elizabeth Frengel, & Nancy Kuhl, Curators

The Children’s Books of Russell and Lillian Hoban

Russell and Lillian Hoban began their decade-long collaboration on books for children with Herman the Loser (1961). Russell Hoban wrote the text, and Lillian Hoban produced the illustrations. Their greatest success was a series of books about a strong-willed badger named Frances. Although Garth Williams illustrated the first book in the series, Bedtime for Frances (1960), it was Lillian Hoban’s artwork for Bread and Jam for Frances (1964), that won a devoted readership. Both Russell and Lillian were trained as artists, but Russell gave up illustration in the early 1960s. The husband-and-wife team settled in to their respective roles as writer and illustrator, and worked in easy partnership. The Hobans produced more than 26 children’s books during their married life, including The Little Brute Family (1966); The Mouse and His Child (1967); and Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas (1971). This exhibition, drawn from the papers of Russell Hoban and Lillian Hoban, explores the collaborative creative process of making children’s books. Featuring original artwork, typescripts, correspondence, artist’s dummies, and finished works that demonstrate, in material form, many layers of collaboration. (EF)

Richard Wright’s Native Son on Stage and Screen

Richard Wright’s classic novel, a bestseller when it was published in 1940, explores the conditions of the life of Bigger Thomas, a poor, black 19-year-old, and the aftermath of Bigger’s accidental murder of Mary Dalton, a wealthy, white college student, culminating in Bigger’s trial, where he is defended by a communist lawyer. Wright wrote the novel to confront readers with the brutality of poverty and white supremacy in Chicago, where he, like Bigger, moved from Mississippi with his family as a boy. Native Son encapsulates the warning that the structures of white supremacy entrap young black men like Bigger Thomas at the peril of all—wealthy families like the Daltons, and impoverished women like Bessie Mears, Bigger’s girlfriend and second victim. After the Book of the Month Club selected the novel for March 1940, Harper printed 170,000 copies, with the first 50,000 selling within two months. Collaborators quickly stepped forward to work with Wright in developing the story for both stage and screen. Both the stage adaptation, produced in 1941, and the screen adaptation, which premiered a decade later, struggled to capture the complexity of Wright’s original portrayal. With anti-communism on the rise and a public seldom eager to confront issues of inequality, Wright and his collaborators fought to find a place for Bigger’s story on Broadway and in Hollywood. (MB)

The best creative collaborations call into question the mythologies of individual genius and invite us to consider the additive possibilities of thinking and working together. Studies in Creativity contemplates a diverse range of collective art-making models by exploring classic and cutting edge works of art and literature devised or authored collaboratively. Artistic partnership, creative competition, the power of the muse, the influence of the impresario—these and other varieties of imaginative or inventive combination and exchange may be shaped by productive challenges or by destructive forces. Love and anger, pleasure and jealousy, conversation and argument—emotion and energy can seem to be multiplied in collaborations. Archives provide uncommon access to the ways works of art develop in a relational context. In documentary records we see several hands at work editing a text, many individuals authoring a stage performance, two lover-artists passing notes back and forth. A social and interpersonal mode of artistic practice comes into focus. Studies in Creativity both explores and celebrates and the spectacular potential when minds come together to make something new. (NK)

The authors and artists represented in the vitrines include Bert Williams and George Walker; the Provincetown Players Theater Company; Pool Productions; Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas; Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French; Delmore Schwartz and James Joyce; Arthur Miller and Elia Kazan; Langston Hughes and Helen H. Watts; Saul Steinberg and Pablo Picasso; Joe Brainard and Ron Padgett; Jane and Stan Brakhage; Gerard Malanga and Andy Warhol; Pippa Anne Fleming and Lisbet Tellefsen; August Wilson and Lloyd Richards; Michael Kelleher; C.D. Wright and Deborah Luster; Mimi Khuc, Monica Ong, Monica Ramos, Simi Kang, and Camille Chew; and the Victory Garden Collective, among others.