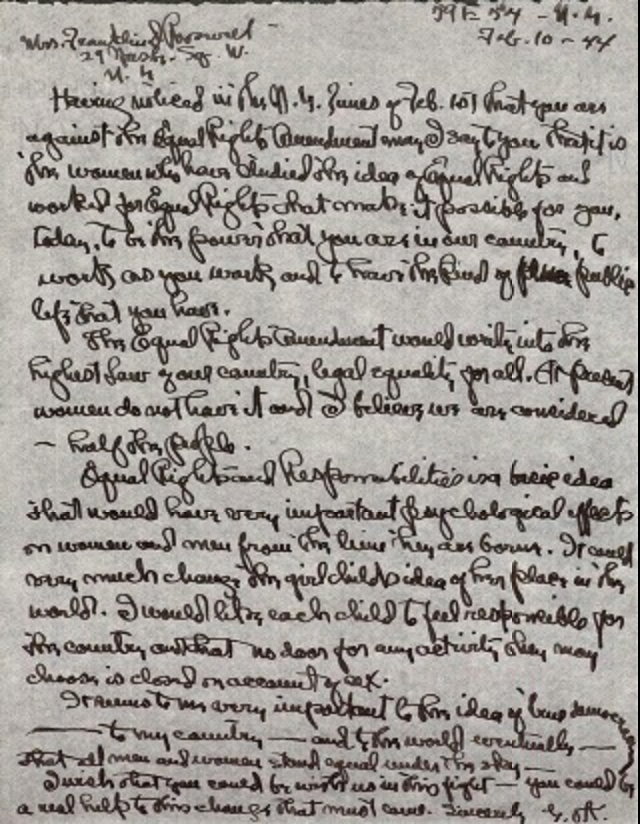

The Beinecke’s collection sometimes includes holograph drafts of materials whose eventual purpose or fate is unclear. This letter—written from Georgia O’Keeffe to Eleanor Roosevelt, dated February 10, 1944—is one such document.

In many literary archives, it is common to find correspondence addressed to the original owner of the archive. We expect, for example, to find letters addressed to Georgia O’Keeffe among her papers in the Stieglitz/ O’Keeffe Archive. It is much less common to find a letter authored by the individual in question—O’Keeffe in this case—as she would presumably have sent the letters she wrote. Outgoing letters would now likely be found in the papers or archive of the person to whom the letter was addressed.

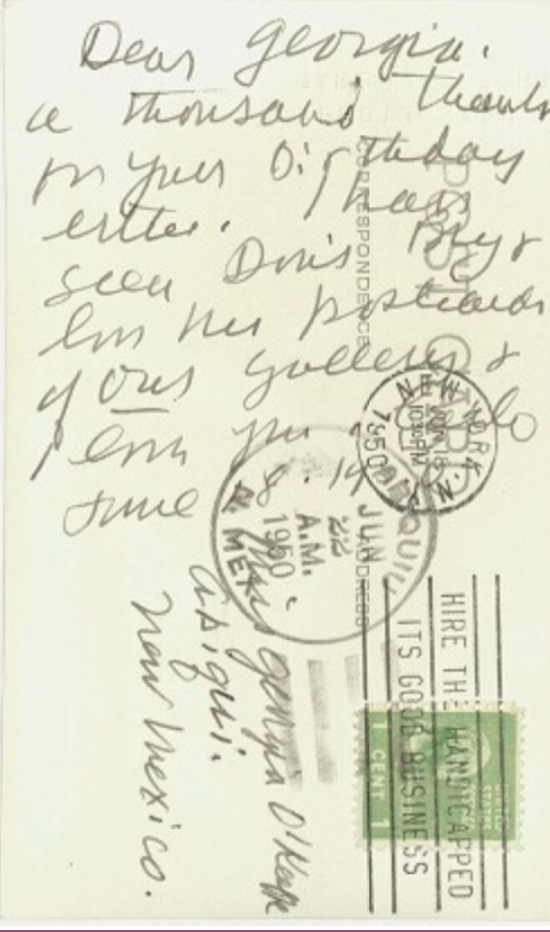

Though we would expect to find this letter from O’Keeffe to Roosevelt among Roosevelt’s papers, it is in the O’Keeffe papers, and there is little evidence concerning whether the letter was ever sent. There is, for example, no correspondence from Roosevelt in O’Keeffe’s papers; collections related to Eleanor Roosevelt at the FDR Museum or the George Washington University Roosevelt Archive do not seem to include other versions or drafts of the letter, postmarked envelopes addressed by O’Keeffe, or other clues.

Whether or not the letter was sent, its contents are of great interest to researchers.

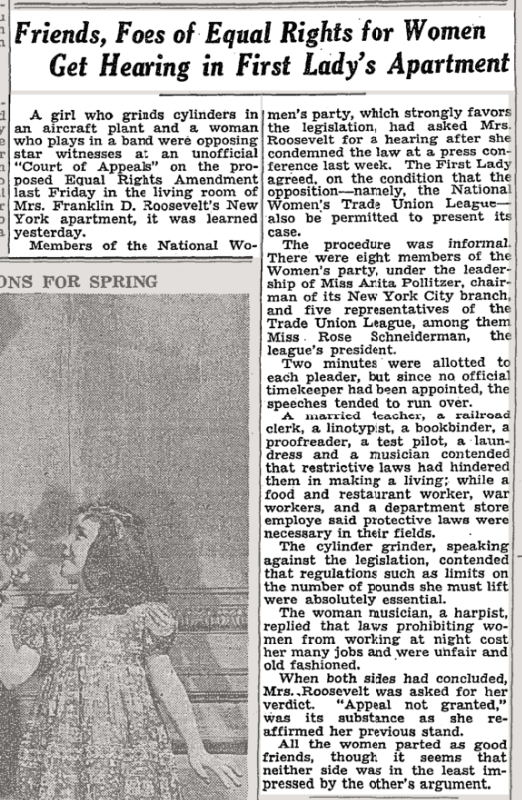

In the first line of the letter, O’Keeffe references an article from “the N. Y. Times of Feb. 10” that indicated that Roosevelt was “against the Equal Rights Amendment”. She presumably refers to the article, “Friends, Foes of Equal Rights for Women Get Hearing in First Lady’s Apartment”. The article describes “an unofficial ‘Court of Appeals’ on the proposed Equal Rights Amendment last Friday in the living room of Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New York apartment,” held at the request of the National Women’s party after Roosevelt “condemned the law” at a press conference. Roosevelt “agreed, on the condition that the opposition—namely, the National Women’s Trade Union League,” which opposed the ERA because they feared it would force poor women and families into starvation, “be permitted to present its case.” Anita Pollitzer (a friend of O’Keeffe’s) attended and spoke in support of the ERA.

At the conclusion of the “informal” presentations, “Mrs. Roosevelt was asked for her verdict. ‘Appeal not granted,’ was the substance as she reaffirmed her previous stand.”

O’Keeffe takes great issue with Eleanor Roosevelt’s stance, asserting “that it is the women who have studied the idea of Equal Rights and worked for Equal Rights that make it possible for you, today, to be the power you are in our country, to work as you work and to have the kind of public life that you have.”

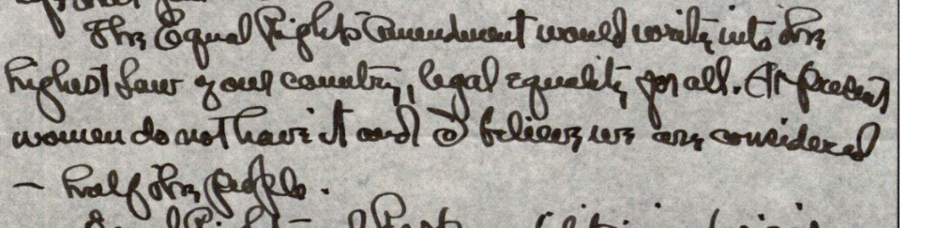

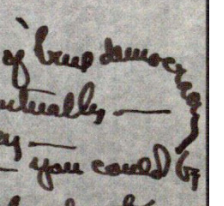

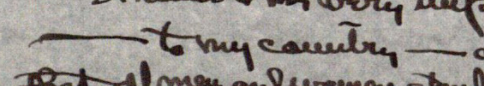

The autograph manuscript of the letter reveals several interesting places of visual emphasis:

- “—half of the people” isolated on its own line, off-set by a dash

- “true democracy” trailing off into the margin, not broken up into two lines

- the long dashes surrounding “—to my country—”

READ Georgia O’Keeffe’s letter to Eleanor Roosevelt (Call Number: YCAL MSS 85).

MORE FROM BEINECKE COLLECTIONS

The Alfred Stieglitz / Georgia O’Keeffe Archive (YCAL MSS 85) and the Alfred Stieglitz/ Georgia O’Keeffe collection (YCAL MSS 104) are housed at Beinecke. The collections includes papers, art objects, and other materials related to the lives of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz.

Highlighted objects include:

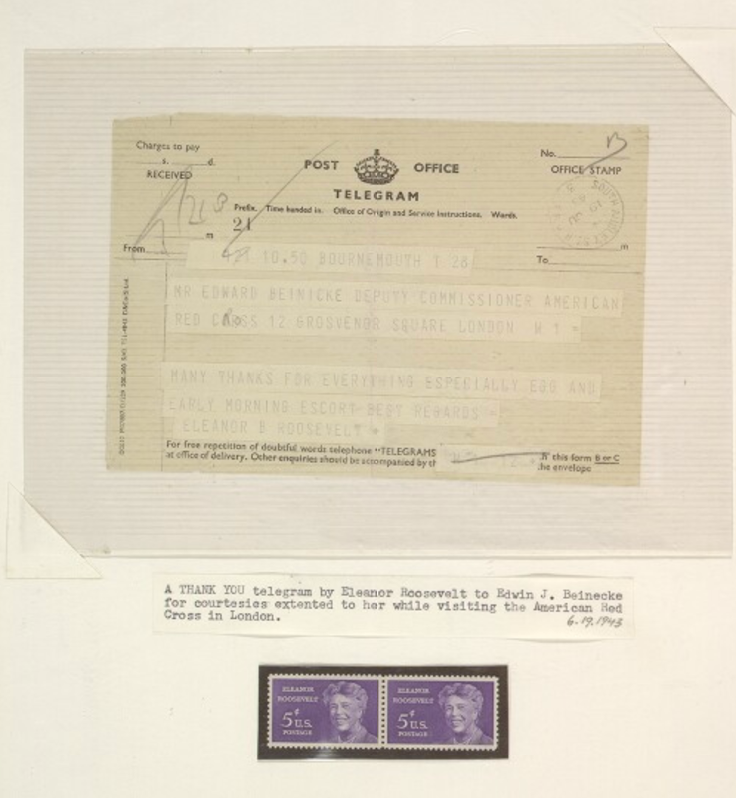

Materials related to Eleanor Roosevelt are available in Beinecke’s Digital Library.

Highlights include:

- Telegram from Eleanor Roosevelt to Edwin J. Beinecke (Call Number: GEN MSS 570)

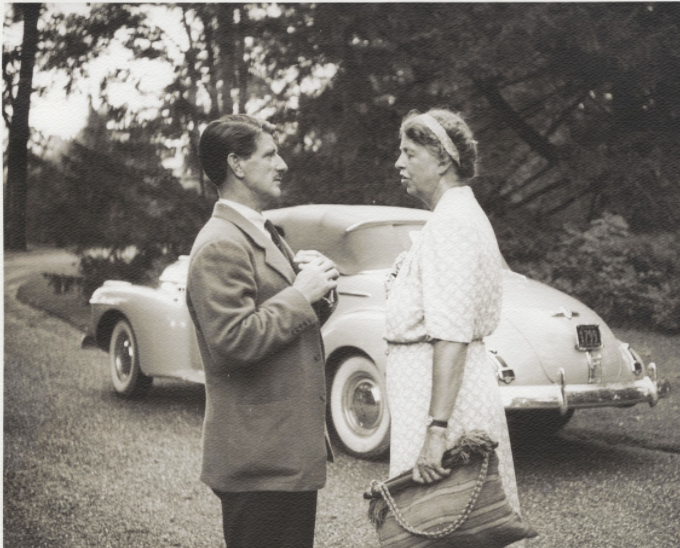

- Photo of Eric Knight and Eleanor Roosevelt, dated 1942 (Call Number: YCAL MSS 40)

MORE ON GEORGIA O’KEEFFE AND ELEANOR ROOSEVELT

Georgia Totto O’Keeffe (November 15, 1887 – March 6, 1986) was an American artist. She was known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. O’Keeffe has been recognized as the “Mother of American modernism”.

In 1905, O’Keeffe began her serious formal art training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and then the Art Students League of New York, but she felt constrained by her lessons that focused on recreating or copying what was in nature. In 1908, unable to fund further education, she worked for two years as a commercial illustrator, and then taught in Virginia, Texas, and South Carolina between 1911 and 1918. During that time, she studied art during the summers between 1912 and 1914 and was introduced to the principles and philosophies of Arthur Wesley Dow, who created works of art based upon personal style, design, and interpretation of subjects, rather than trying to copy or represent them. This caused a major change in the way she felt about and approached art, as seen in the beginning stages of her watercolors from her studies at the University of Virginia and more dramatically in the charcoal drawings that she produced in 1915 that led to total abstraction. Alfred Stieglitz, an art dealer and photographer, held an exhibit of her works in 1917. Over the next couple of years, she taught and continued her studies at the Teachers College, Columbia University in 1914 and 1915.

She moved to New York in 1918 at Stieglitz’s request and began working seriously as an artist. They developed a professional relationship and a personal relationship that led to their marriage in 1924. O’Keeffe created many forms of abstract art, including close-ups of flowers, such as the ”Red Canna” paintings, that many found to represent female genitalia, although O’Keeffe consistently denied that intention. The reputation of the portrayal of women’s sexuality was also fueled by explicit and sensuous photographs that Stieglitz had taken and exhibited of O’Keeffe.

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz lived together in New York until 1929, when O’Keeffe began spending part of the year in the Southwest, which served as inspiration for her paintings of New Mexico landscapes and images of animal skulls, such as ”Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue” and ”Ram’s Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills.” After Stieglitz’s death, she lived permanently in New Mexico at Georgia O’Keeffe Home and Studio in Abiquiú, until the last years of her life when she lived in Santa Fe.

(Source: Beinecke Digital Library)

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt (October 11, 1884 – November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat and activist. She served as the First Lady of the United States from March 4, 1933, to April 12, 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four terms in office, making her the longest-serving First Lady of the United States. Roosevelt served as United States Delegate to the United Nations General Assembly from 1945 to 1952.

President Harry S. Truman later called her the “First Lady of the World” in tribute to her human rights achievements.

Roosevelt was a member of the prominent American Roosevelt and Livingston families and a niece of President Theodore Roosevelt. She had an unhappy childhood, having suffered the deaths of both parents and one of her brothers at a young age. At 15, she attended Allenwood Academy in London and was deeply influenced by its headmistress Marie Souvestre. Returning to the U.S., she married her fifth cousin once removed, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, in 1905. The Roosevelts’ marriage was complicated from the beginning by Franklin’s controlling mother, Sara, and after Eleanor discovered her husband’s affair with Lucy Mercer in 1918, she resolved to seek fulfillment in leading a public life of her own. She persuaded Franklin to stay in politics after he was stricken with a paralytic illness in 1921, which cost him the normal use of his legs, and began giving speeches and appearing at campaign events in his place. Following Franklin’s election as Governor of New York in 1928, and throughout the remainder of Franklin’s public career in government, Roosevelt regularly made public appearances on his behalf, and as First Lady, while her husband served as president, she significantly reshaped and redefined the role of First Lady.

Though widely respected in her later years, Roosevelt was a controversial First Lady at the time for her outspokenness, particularly on civil rights for African-Americans. She was the first presidential spouse to hold regular press conferences, write a daily newspaper column, write a monthly magazine column, host a weekly radio show, and speak at a national party convention. On a few occasions, she publicly disagreed with her husband’s policies.

She launched an experimental community at Arthurdale, West Virginia, for the families of unemployed miners, later widely regarded as a failure. She advocated for expanded roles for women in the workplace, the civil rights of African Americans and Asian Americans, and the rights of World War II refugees. Following her husband’s death in 1945, Roosevelt remained active in politics for the remaining 17 years of her life.

(Source: Beinecke Digital Library)

- Gabrielle Colangelo Y’21

Yale Collection of American Literature Student Research Assistant