In honor of the new exhibition “Gather Out of Star-Dust: The Harlem Renaissance & The Beinecke Library” and of the Beinecke Library’s year-long celebration of the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters, James Weldon Johnson Fellow Emily Bernard gave the first “Mondays at Beinecke” talk about collection founder Carl Van Vechten, his role in the Harlem Renaissance, and in shaping the Johnson Memorial Collection at Yale.

Emily Bernard, Professor of English and Critical Race and Ethnic Studies at the University of Vermont, is the author of Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance: A Portrait in Black and White. Her first book, Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Her essays have been published in Best American Essays, Best African American Essays, and Best of Creative Non-Fiction. Bernard has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the W.E.B. DuBois Institute at Harvard University.

The exhibition “Gather Out of Star-Dust: The Harlem Renaissance & The Beinecke Library” is on view Friday, January 13, 2017 to Monday, April 17, 2017.

Professor Bernard’s “Mondays at Beinecke” remarks, below, were delivered at the Beinecke Library on January 23, 2017.

—-

My first book was called Remember Me to Harlem. It was an edited collection of a forty-year correspondence between Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten. People often assume that what drew me to the letters was Langston Hughes. He is revered—“our Negro man of letters,” poet Elizabeth Alexander has described him, “the poet of the race.” His talent was undeniable. But he was also extremely seductive, with wavy dark hair and gentle, unassuming ways. I am certain that his fame in inextricably bound up with his good looks. He was easy to look at, and easy to love.

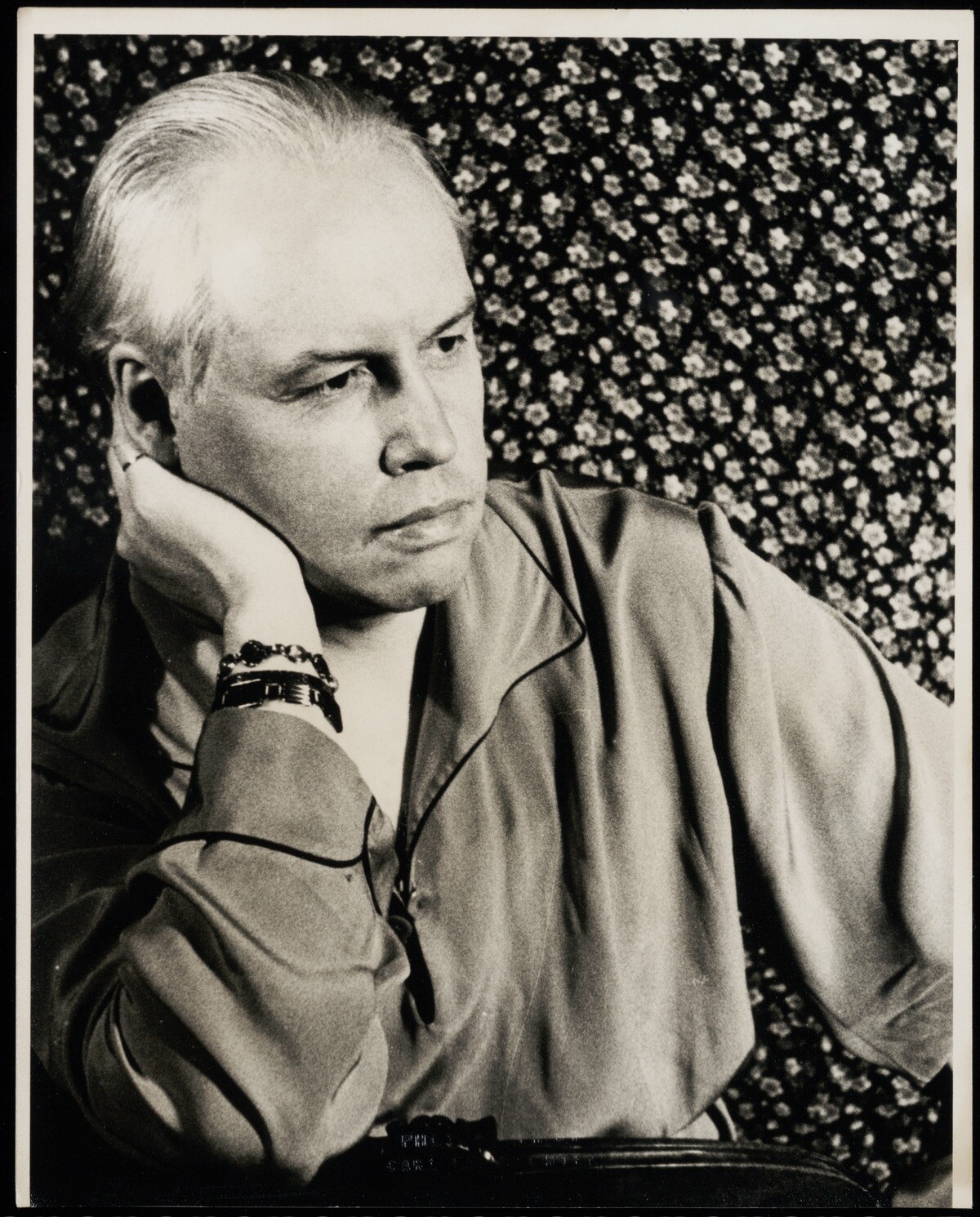

Van Vechten, however, had buck teeth so big that he refused to smile broadly in photographs. He was gangly and strange; gauche, domineering, and boorish. He was rude and bullheaded. He captured my affections immediately.

There are many chapters in the story of the life of Carl Van Vechten. My most recent book, Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance: A Portrait in Black and White, is less a biography of the man than a story of set of ideas and ideals that coalesced during the period we know as the Harlem Renaissance around the concept of the New Negro, a movement, a concept, a trope, that represented a need to re-conceptualize the face of the race. Undeniably, Carl Van Vechten was a fascinating person. But to me he has always been most fascinating as an occasion—he himself served as a kind of canvas, onto which black artists and intellectuals created images of themselves as both artists and black artists.

Before he died in 1964, Carl Van Vechten had been a far-sighted journalist, a best-selling novelist, an exquisite host, an exhaustive archivist, a prescient photographer, and one of the most controversial figures in the history of African American culture. He was born in 1880 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He was reborn in 1920s New York, a setting for the period known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Van Vechten’s relationship to the Harlem Renaissance began with a single friendship. Van Vechten met the black novelist and journalist Walter White in 1924. The two men had been introduced by their mutual publisher, Alfred Knopf, upon the publication of The Fire in the Flint, a novel about the lynching of a black physician and war veteran. “In about a week after that I knew practically every famous Negro in New York because Walter was a hustler,” Van Vechten recalled in 1960. At the time, he and his wife, Odessa-born actress Fania Marinoff, were living in an apartment on West 55th Street, which Walter White dubbed the mid-town office of the NAACP.

By the mid-1920s, Carl’s passion for black people and culture had taken full hold of him. Because it was an unusual road for a white person of his era to take, it was not, in fact, unusual for Carl Van Vechten, considering his background. His childhood had prepared him to go against the current.

Early on, he had learned from his parents to respect black people and to challenge the cultural conventions that considered blacks and whites to be naturally and forever separate. Carl would always remember how his father instructed him to refer to the black people who worked on their property as Mr. and Mrs. at a time when it was uncommon for whites to refer to blacks with honorifics. Charles helped found the Piney Woods School in Mississippi, an elementary school for black children, which was established in 1909 and remains in operation. In 1960, Carl described his father as sober and kindhearted, a man with “no prejudice whatever.”

Carl Van Vechten took great pride in discovering new talent, and during the Harlem Renaissance, publicizing new black talent was nearly a vocation. He was a powerful “fan” and a very useful friend to have. He was famous for his parties, events at which powerful whites were able to meet black artists on the most intimate terms. All of Harlem was aware of these parties. Black newspapers and magazines reported on them regularly. A Harlem legend goes like this: a porter greets Mrs. Vincent Astor at Union Station with a curious familiarity. “How do you know my name, young man?” She asks. “Why, I met you last weekend at Carl Van Vechten’s,” he responded.

Van Vechten was a dedicated and serious patron of black arts and letters, but his genius as a host led to a brand of “social work” that not only helped secure support for black artists, it also helped break down racial barriers in essential, interpersonal ways, an achievement that legal changes alone simply cannot accomplish. At Van Vechten’s West 55th street home, cocktails were garnished with race uplift.

Learning the hustle à la Walter White enabled Van Vechten to appreciate the difference between black people as he had imagined them from a distance, and black people as they existed in the flesh. I use the word” deliberately. Van Vechten and Marinoff were married for fifty years. Yet Van Vechten was enamored of the black male body. The fact that Van Vechten was gay rankled blacks that were suspicious of his motives for going uptown, where there was a relatively more tolerant attitude toward homosexuality. It was an oasis for its own gay population, as well for white homosexuals who traveled uptown for sanctuary and excitement,” explains Kevin Mumford. Just as often as Carl Van Vechten feted Harlem in his midtown home, he conducted tours of Harlem for white visitors who would have been too timid to go on their own. His tours were so famous that they inspired a contemporary song, “Go Harlem!” by Andy Razaf, whose lyrics encouraged readers to “Go inspectin’/like Van Vechten.”

Van Vechten was a white man who loved blackness, in general. There were other whites that enjoyed and fostered Harlem and the artists we have come to associate with the Harlem Renaissance. But Carl was singular in the depth and breadth of his passion for all things black. As I said, this fervent longing for blackness has always been considered questionable. He loved black bodies, and he loved the spectacle of blackness, just like any other white pleasure-seekers who made pilgrimages uptown. Like those he spirited uptown, Van Vechten was attracted to the tolerant atmosphere toward homosexuality that colored Harlem nightlife.

His sexuality is a reason Van Vechten has been considered so problematic by scholars of African American culture. The sociologist Harold Cruse, for instance, in his 1967 book The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, described the Negro Renaissance as having been “emasculated” and condemned all Harlem-based creative innovations as “whitened.” But while Carl’s early interest in blackness may have been inspired by sexual desire and his fascination with primitivism, these features were not what sustained his interest in black people and black culture, and his beliefs changed and expanded over the course of his forty-year love affair with black art.

The boundary between white and black New York was porous and opaque. Van Vechten moved between these borders with reckless irreverence. He crossed other lines, as well, expressly those having to do with language, conventions about what white people can and cannot say about black people. Van Vechten was unabashedly enchanted with fantasies of primitivism, which he considered the birthright of all black people, and he wrote with reverence with what he saw as the “squalor of Negro life, the vice of Negro life.” He understood the nasty implications of these stereotypes, but he was pragmatic. He wrote: “Are Negro writers going to write about this exotic material while it is still fresh or will they continue to make a free gift of it to white authors who will exploit it until not a drop remains?”

In his journalism, Carl urged black writers to take advantage of white interest in black life. The single theme echoed throughout his writing about black literature, theatre, and music. “It is a foregone conclusion,” he wrote in “Moanin’ Wid a Sword in Mah Han,” an essay about black spirituals, “that with the craving to hear these songs that is known to exist on the part of the public, it will not be long before white singers have taken them over and made them enough their own so that the public will be surfeited sooner or later with opportunities to enjoy them, and—when the Negro tardily offers to sing them in public—it will perhaps be too late to stir the interest which now lies latent in the breast of every music lover.”

Van Vechten warned that if black artists failed to exploit the “wealth of material” at their fingertips, some enterprising white artist would do it. And just as he predicted, one particularly enterprising white writer did. Carl’s fifth novel, Nigger Heaven, was published in 1926.

For many people, already suspicious of Van Vechten as a white interloper, and unwelcome party-crasher at the gates of black culture, Nigger Heaven was the last straw. “Anyone who would call a book nigger heaven would call a negro a nigger,” wrote one reviewer of the book, summing up popular sentiment about its author.

No one disapproved more strongly than his own father. The elder Van Vechten wrote to his son: “Your ‘Nigger Heaven’ is a title I don’t like…I have myself never spoken of a colored man as a ‘nigger.’ If you are trying to help the race, as I am assured you are, I think every word you write should be a respectful one towards the black.”

A week later, he wrote again: I note what you have to say about the title to your new book, including that statement that some of your negro friends agree with me—You are accustomed to “get away” with what you undertake to do: but you do not always succeed; and my belief is that this will be another failure, if you persist in your “I shall use it nevertheless.” Whatever you may be compelled to say in the book, your present title will not be understood & I feel certain you should change it.” The senior Van Vechten was correct. Much of the violent objection to Nigger Heaven, in 1926 and today, begins and ends with the title.

Nigger Heaven is largely a tepid love story about two young Harlem intellectuals. His protagonist has lost contact with the primitive within, and fails professionally and romantically because he represses his essential, ineffable racial characteristics—black difference.

Even though Nigger Heaven hurt Carl’s reputation, it hardly broke his stride. He began to take photographs of famous friends, acquaintances, and strangers. Then he turned his eye toward establishing collections.

Van Vechten established collections of materials from his personal archives around the country. At, he established the Florine Stettheimer Memorial Collection of Books about the Fine Arts, as well as the George Gershwin Memorial Collection of Music and Musical Literature; at the New York Public Library, he established Carl Van Vechten Collection, which was comprised all of his written materials, from drafts to revised editions; correspondence; and clippings about his work and social life; and at Yale, the Anna Marble Pollack Memorial Library of Books about Cats. In addition, he donated a collection of his photographs of famous black people to Wadleigh High School in New York City, and presented the high school in Cedar Rapids that he had attended with a similar collection.

In addition, Carl inspired his friends (among them, Georgia O’Keefe, Lawrence Lagner and Armina Marshall, Mabel Dodge Luhan, and Gertrude Stein) to establish their own collections. About the George Gershwin Memorial Collection of Music and Musical Literature, he told William Ingersoll for “Reminiscences”: “I said at the time that I thought this would interest people of the other race to go and look up things in their respective places.” It’s because of Carl Van Vechten that I ended up in the Beinecke library at Yale, where he established the James Weldon Johnson collection of Negro Arts and Letters, as it was then called.

Carl began collecting materials for Yale in the late 1930s, not long after his longtime friend James Weldon Johnson died tragically in an automobile accident. The two men had made each other executors in the other one’s estate. Van Vechten decided to establish the collection in Johnson’s name. He sensed—probably correctly—that the bad feeling generated by Nigger Heaven would discourage black artists and writers from contributing their materials. Van Vechten pestered, cajoled and sweet-talked friends, acquaintances and strangers to give their materials—meaning manuscript drafts, correspondence, and personal items— to Yale.

He was not only committed to the collection, he was determined that the collection be overseen by an African American librarian. While Yale’s head librarian, Bernhard Knollenberg did not hesitate to accept Carl’s black materials, when it came to adding a living, breathing black human being to the library staff—that became a different matter altogether.

After presenting Knollenberg with the names of several African Americans familiar with the world of the library, Carl presented Knollenberg with the resume of his dear friend Dorothy Peterson. Peterson and Knollenberg had already met. A year before Dorothy set her sights on the job at Yale, they were introduced at a party at Van Vechten’s home. On behalf of his wife and himself, Knollenberg thanked Van Vechten for the evening in a letter he sent the following day. “We had a delightful time last evening at your house. Once or twice when I have been in company with Negroes there has been an air of constraint. Last night I felt as much at home as I have ever felt in a party composed largely of people I was meeting for the first time, and I thought everyone else ‘felt as free and easy’ as I did.” He was particularly taken with Gladys White, Walter’s wife, and Dorothy Peterson.

Carl replied to Knollenberg immediately. “Thanks a lot for your letter and we are happy you and Mrs. Knollenberg had a good time, but those were not Negroes, they were old and valued friends of ours whom we have known intimately, and see frequently, for twenty years!” he explained. It was not the first time he would provide Knollenberg with a little race education (a few weeks before, he had instructed Knollenberg to spell “Negro” with a capital N). Dorothy Peterson enjoyed the party, too, and also sent a thank-you note to Van Vechten. In his reply, Carl confided only that Knollenberg had called Dorothy “one of his favorites!!”

Carl had not anticipated Dorothy’s interest in the job at Yale, but once she expressed it, he made it his mission to secure the position for her, and Knollenberg was pleased to include him in his discussions with Dorothy. Carl mailed her a copy of the letter he had written Knollenberg describing his surprise in Dorothy’s interest in the job, and assured Knollenberg that he had tried to dissuade her but had resigned himself to the fact that Knollenberg’s encouragement had clearly won out. Since Dorothy and Knollenberg were both determined to proceed, he said, he itemized Dorothy’s singular qualifications. “She knows, or knew before they died, most of the writers intimately. Her background couldn’t be better. Her knowledge of languages would be of immense assistance,” Van Vechten wrote. “If she does go into this, it will be seriously, and with her face towards the future and what that may bring her and the Collection. Let me know what you decide.”

He was more cautious in his communication with Dorothy. “I am glad in my heart that you have the nerve to live on a biscuit, but don’t ever say I made you do this,” he warned. But he was excited about the prospect of Dorothy working at Yale. She would adore the library itself, he told her. At the time, the James Weldon Johnson Collection was housed at Sterling Memorial Library, which was relatively new, having been built in 1930. In 2003, seventy years after she joined the library staff, Marjorie Wynne described her first impression of Sterling. “Everything was new and wonderful: the towering nave swept boldly forward (unhindered by a central staircase), and every surface–glass, iron, stone, and wood–was alive with scenes and inscriptions from books and manuscripts.” It was magnificent, Carl reported to Dorothy. Her brother Sidney would be impressed, too. “He’ll think you are going to be Pope or something!”

Behind the scenes, Van Vechten was managing a problem: Bernhard Knollenberg, who, Van Vechten believed, was dragging his feet on the issue of Dorothy’s hire. Carl pestered him in a letter. Dorothy was excited, he said, and insists that this is what her whole life has been leading up to and seems to be very serious about going ahead. I think it would be unfair to let her do this if you were opposed to her acceptance as a possible librarian.” She was eager for resolution–and so was Carl. Why wouldn’t Knollenberg give them an answer? Carl implored Knollenberg to be frank with him, at least, and promised to keep his confidence, but he was primarily looking out for Dorothy, who was bothered by Knollenberg’s silence, which bothered Carl in turn.

Knollenberg’s initial enthusiasm had waned, as it turned out, and he was now disinclined to offer Peterson the job. First, there was the matter of her professional training. Like previous applicants, Peterson was not a trained librarian, Knollenberg said, and he didn’t have the time or the resources to train her himself. Second, there was the matter of the salary; Knollenberg had decided that it wasn’t high enough for her. “By its very nature, a curatorship has to be primarily a work of love,” he informed Van Vechten, who had predicted this reaction from Knollenberg; he had coached Peterson two weeks earlier: “When you write Mr. K, write something short and simple like this: ‘In spite of everything, I think Id like to try it. When may I come to talk to you about it?’”

Finally, Knollenberg got to the point: race. “With a few exceptions, the Caucasians in New Haven with whom Miss Peterson will come into contact, are less liberal in their attitude toward Negroes than the New York Caucasians with whom Miss Peterson has associated.” Perhaps a southerner, used to staying in his place, would fare better? From the perspective of the South, New Haven would seem more tolerant than it actually was. As for Dorothy Peterson, “living as she has in New York she has come into association with an exceptionally liberal minded group of Caucasians, and any change will be a change for the worse in that particular.” He didn’t believe Peterson had fully considered this aspect of the job.

Uncharacteristically, Van Vechten took a few days before responding to Knollenberg. “I think the engagement as Curator of the Collection of a Southerner who would be willing to remain in any way socially subservient, would completely defeat the purpose of the Collection,” he said. “To my mind, the more sophisticated the person engaged, the better, and I think one of the essentials should be a wide acquaintance, white and black, with individuals who are interested in movements and problems of the race.”

With regards to Dorothy: “ I do not anticipate any troubles along the lines you speak. In the first place, even if everybody in New Haven snubbed Miss Peterson, an eventuality I am not expecting, she knows plenty of people, East, West, North, and South, who would drop by to see her.” And it wasn’t true that Negroes found Yale inhospitable, he contended. Playwright Owen Dodson, for instance, was much admired by his peers at the Yale School of Drama. And what about Paul Robeson? He and his family were the only black residents in the very small town of Enfield, Connecticut. They were valued members of their community, and their son was one of the most popular and successful boys in school. “If you reply that these are special cases,” Van Vechten cautioned, “I would say that is exactly what I mean: Anybody who would know the authors and contents of the books in the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection and know how to enlarge the Collection and encourage endowments would have to be a very special case indeed!”

Knollenberg felt misunderstood and offended. “Dear Mr. Van Vechten, You have inadvertently done me an injustice,” he claimed. “No one could be more opposed to having a Negro who is of the subservient (‘Uncle Tom’ as Richard Wright calls it) type. I know some southern Negroes who are decidedly not subservient.”

Van Vechten attempted to soothe Knollenberg’s feelings in his reply. “I never questioned your attitude in the matter of Negroes. I have great faith in that. What I did gather from your letter was that a Negro who was accustomed to concede the erratic behavior of Southern whites might find it easier going in your library. This may be a correct assumption. My own experience with Southern intellectual Negroes who pretend on the surface to accept conditions is that underneath they are generally bitter and neurotic and are likely to be good haters.” He asked permission from Knollenberg to be frank on all matters pertaining to the collection, requesting that Knollenberg receive his opinions in the spirit of honesty and respect. He deferred to Knollenberg’s greater understanding of the library, and in response, Knollenberg conceded that Van Vechten might indeed have a point. Knollenberg’s proposal continued to rankle Van Vechten, however, and although he encouraged Dorothy to make her own decision about whether to pursue the position at the library.

With little encouragement from Knollenberg, Dorothy eventually gave the idea up. The Beinecke Library at Yale would not have an African American curator until 2008, forty-three years after Van Vechten’s death.

Carl Van Vechten lived to see the ascent of the Civil Rights Movement, and he cheered and supported the activists, and hoped that new era would produce new, good art. Carl Van Vechten had many lives, and blackness was the story of at least one of them. He walked the messy, murky line between appropriation and appreciation boldly and unapologetically.

I believe Van Vechten’s black life story has something to offer in this current climate where racist violence seems commonplace. Racism happens out there but it also happens in here, in the interiors of our lives. My inspiration for writing about Van Vechten was the intimacy he enjoyed with his black friends, like James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen, Dorothy Peterson, Nora Holt and Ethel Waters. They loved Carl the way he loved blackness: with great and abiding passion. They loved Van Vechten because he loved blackness.

I have long been fascinated by the way race did and did not play a role in their friendships. It’s the same way I experience race in my own intimate relationships. When Van Vechten and Nella Larsen, for instance, talked about race, they did so with both irreverence and awe. Blackness—style, culture, art—was wonderful and humorous to all of them. They ignored conventional boundaries of decorum when they talked about racial difference, just as they flouted the social logic of Jim Crow by enjoying each other’s company at all.

There are important rational arguments to make about whether or not Carl Van Vechten appropriated black art and enforced racial stereotypes. There are serious intellectual critiques to make of Carl’s attachment to blackness. But there is also mystery. The root of any passion is always a mystery. It was with the beautiful mystery of blackness itself that Van Vechten fell desperately, unquenchably in love.

As I researched Van Vechten’s life, I didn’t so much ignore the troubling aspects as I did follow them into deeper territory. His fixed ideas about black art represented facets of his public position on racial difference. But in his private world, there were subtleties, nuances, contradictions, and layers. His bonds with black friends were sparked by his admiration of the art they presented to the public, but they were maintained by those ineffable qualities that sustain any deep bond.

“You’re going to get into trouble,” a friend warned years ago when I began writing about Van Vechten. My friend meant it as a compliment. For a long time I didn’t think I was up for it. But then another friend introduced me to a collection of poems by Michael Harper called Use Trouble. She suggested that I consider the title itself as a piece of advice.

I continue to be drawn to Van Vechten because of the trouble that he caused. In his abundant and bottomless love for blackness, the story of Carl Van Vechten is a hopeful one. He took pleasure in deep interracial communion that sometimes feels impossible in our hopeless racial climate. I keep writing about Carl Van Vechten because I believe that there are readers like me out there, who will find inspiration in the trouble Van Vechten caused, the lines that crossed, and the passion he inspired while doing both.

–Emily Bernard