Call Number: GEN MSS 1453, Series II

Collection: Jim Fouratt Papers

Who Is Jim Fouratt?

Jim Fouratt was born on the 23rd of June in 1941. He is a gay rights activist, actor, and former nightclub impresario, who is also revered as one of the thinkers at the forefront of the gay rights movement and AIDS crisis. He is best known for his role in the Stonewall Riots and as co-founder of the Danceteria, an nightclub/dance club that operated in New York City from 1979 to 1986.

Growing up, Jim Fouratt has always faced issues with public discrimination due to his sexuality. Though he was accepted into Harvard University, he was unable to matriculate as his family could not afford it. Thus, he enrolled in St. Peter’s Seminary in Baltimore, but he was subsequently expelled from the school due to his gay identity. Following his expulsion, he moved to New York City in 1960 to begin his life.

Jim Fouratt mostly worked in media before and during his strong political work. He started out in acting, as he studied under Lee Strasberg, the founder of the Group Theatre and the Actors Studio as well as the mentor to many prolific actors, such as Marilyn Monroe, for the better part of a decade. He later joined Actors Equity and debuted on Broadway in The Freaking Out of Stephanie Blake, a comedy play starring Jean Arthur, written by Richard Chandler, and produced by Cheryl Crawford, but it never opened past previews.

He then switched to the music industry. In 1969, the same year as the Stonewall Inn Riots, he served as an assistant to Clive Davis, the president of Columbia Records. He became the manager at Club Hurrah in 1978 and worked at many other clubs, such as Studio 54, until he opened his own club with Rudolf Pieper, called Daneteria. In the early 90s, he worked as Director of National Publicity at Rhino Records, and then worked as Vice President of A&R (Artists & Repertoire) of Mercury Records from 1995 to 1999.

Since then, he has switched to journalism, where he has been a pop culture critic for Billboard and Rolling Stone, integrating his experience in the music industry with writing. He has written at other publications across the nation, including Gay City News. He is currently an editor for Westview News, a newspaper based in Manhattan’s West Village.

Gay Rights Activism

In 1965, Fouratt began to take activism much more seriously as he demonstrated for his beliefs, such as the Times Square Anti-Vietnam War demonstration. This set him up to be much more active in following gay rights movements, beginning primely with the Stonewall Inn Riots, which he prefers to call the “Stonewall Rebellion”. He was present at the first night (of three) of the rebellion at Stonewall Inn for which he gave a first-hand account to Paper Magazine:

I happened to be coming home from my job at Columbia Records. I saw a sole police car outside of the Stonewall Inn. I was out in the New Left movement and the anti-war movement and there was an incredible amount of homophobia—in the old and new left. Like a good ’60s radical, I went to see why that car was there.

He was present all three nights of the Stonewall Rebellions, culminating in his co-founding of the Gay Liberation Front: a pioneering organization in the liberation of queer people that inspired others across the country following the Stonewall Rebellions. Part of what made the Gay Liberation Front a well-known and inspirational organization was the fact that it was the first organization to cite queerness (specifically, homosexuality) in its name. In addition to the nominal pioneering, he took a photograph of his then partner, Peter Hujar, for a Gay Liberation Front recruitment poster, which premiered on the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion.

He had a hand in the creation of many of these off-shoot organizations in New York City, such as the Lesbian and Gay Community Service Center, the Gay Community Service, and WIPE OUT AIDS (now, H.E.A.L).

The Notebook

The Jim Fouratt Papers Collection

In our archives, the Beinecke has a whole collection called “The Jim Fouratt Papers” in which we have Jim’s personal notebook that he used circa 1984 containing his thoughts, his muses, his emotions, and his plans regarding gay rights, the AIDS epidemic, and substance abuse. In this notebook, we are able to see the transitions of topics on the front of his mind, from recipes to make for supper one night and lists of foods that are bad for AIDS patients to lectures on consciousness and lectures on gay parenting.

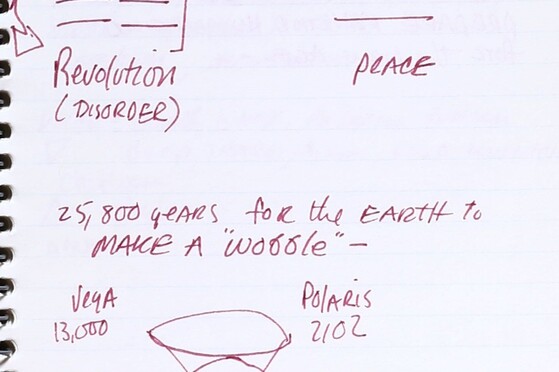

Before the Mentions of AIDS

The first few pages of the recipe begin with a couple of recipes for rice dishes and different kinds of soups. Then, only a few pages later, he has notes on a Ed Estro(?) lecture on consciousness, in which he scribbles lines, such as “universe transforms itself into human being”, and images, such as a spiral with materialization (marked with a right-side up triangle), consciousness (marked with a upside-down triangle), and conception (no marking) around the spiral. Though these triangles appear throughout the notebook in different places, these entries show how he lived a life without the direct concerns of the AIDS epidemic (at least not to the point where they have appeared in this notebook yet).

Following the notes on this lecture, there is a large break of pages that are blank. This may demarcate the transition between the more casual entries at the beginning of the notebook to the more serious thoughts in the entries following the break, most directly relating to his activism in response to the AIDS epidemic.

AIDS at the Forefront

The first entry in the notebook following this large page break is contextualizing the lecture a couple pages previous with hints of his application to queer liberation and life, with lines of “our history is a spiral path”, “meridian are in all things nature: plants, animals, man”, “medical problems: excessive energy, lack of energy, stagnant”, and “on touching”. The final two lines outlining ideas of the basis of medical problems directly connects to the omnipotent AIDS crisis and the “on touching” feels directly connected to gay intimacy (which also connects to AIDS). The following pages are not clear to me what they are saying, but the grounding of the recurrent triangle iconography is taking hold to be continued throughout.

The following couple of pages contain these triangles again and their association to certain foods. At the top of the page, he has the term “degeneration”(?), which he describes as “begins to interfere with the functioning of the organs — can be connected to regeneration”(?). Below that he has two columns, each headed by a different facing triangle, upside-down on the left correlated with the word “xtremes”[sic] and right-side-up on the right. In the upside-down column, he has listed foods such as sugar, recreational alcohol, coffee, ice cream, and sweet butter, foods that are generally considered “healthy”, while there is also tropical fruit, tomato, and eggplant in this list, which are fresh produce generally endorsed as good foods to eat. In the right-side-up triangle, there is poultry, salt, eggs, hard cheeses, and fish listed, foods generally high in protein. On the next page, he has an evaluation of blood, with the right-side-up triangle being correlated with red blood cells and the upside-down triangle correlated with white blood cells. These two lists and associations with the triangles gives more proof that the right-side-up triangle indicates something that is “good” or “healthy” or “increasing”, while the upside-down triangle is something that is “bad” or “unhealthy” or “decreasing”.

A way that we can know that this is in direct relationship with his education and activism in the AIDS epidemic is that the next page has in large letters, all caps, and — in some places — is in bold:

STRANGE STORIES TO TELL AIDS FRIENDS

NOT GEARED TO AIDS FRIENDS

This may show that those previous pages are directly in response to the impending AIDS epidemic: these two lists of food may be a taken from a lecture in which the lecturer — “he” — may be telling stories that Fouratt may not think are geared toward “AIDS friends” and may be confusing his AIDS friends more by talking about the standard micro diet.

Another interesting part of this is the reference to the people in his life who have AIDS as “AIDS friends”. Though this may be the way of referring to those you know with AIDS — in reference to the fact that they have it — I find it very interesting. I try to think about how similar formatting may work nowadays — such as “black friends”, “trans friends”, “liberal friends” —, and I am unsure that they are really comparable. In those examples that I brought up, they are demographics of these people: fundamental parts of their identities to which they can find community in those demographics. In the case of “AIDS friends”, having AIDS does not seem to fit in this category. At their core, they are not fundamentally people who have AIDS. Though it may take on an increasingly important role in their lives and become integral parts of their identity and means for finding community after their diagnosis, having a deadly disease feels a bit different than your skin color, your gender identity, or your political affiliation. Because I am not a person with AIDS or have ever known anyone who is, I cannot speak on behalf of this community, but it feels important to mention the verbiage used at the time. For this descriptor to be alerting —at the very least interesting — to me is quite telling in regards to how our language around identity has changed since this time, even within the LGBTQ+ community that tends to spearhead advancement in respectful language and reference.

After the notes ostensibly on a lecture or talk of some sort, there is a page break before a new set of notes on a new lecture topic. (Fouratt was very eager to attend lectures and gain knowledge, which harkens back to his qualities leading to his acceptance into Harvard). At the top of this page, Fouratt writes, “Diagnosis - evaluation of ourselves thru to colors”. Below this, he associates five colours — red, yellow, white, black, and green — to different points of the day and different seasons. He also has five types of people, represented by natural entities: fire, soil, metal, H20, and tree. The notes on this lecture underscore Fouratt’s hunger for knowledge and integrates his penchant for existentialism for the way the world works and how people work.

These qualities eventually do tie back to the topic at the forefront of his mind due to the AIDS epidemic: the body and how everything is connected to it. So, he eventually connects each of the natural entities to a different part of the body as well as each of the colours to a part of the body.

This shows how desperately he is searching for a connection between the soul and the body (and its impairments): a heuristic to understand sickness and how to heal it.

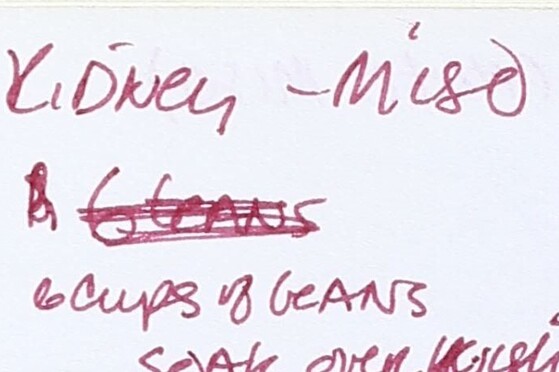

We now come across another long section of food recipes. We can now approach this with the understanding that these recipes are unlikely just what he is thinking about making for supper the following night, but in deep consideration of what is best to eat as a person with AIDS, though he does not have it. We also get more direct evidence of this as the top of some of the pages has a body part written next to the title of the recipe, as if these are recipes that are specifically for the improvement of these body parts, for those struggling with it. For example, he has written “Kidney — Miso” at the top of a miso soup recipe.

After a long string of recipes in his notebook, the next entry we get is a meditation on sickness and health, life and death. Fouratt could have just been documenting his own thoughts, or these could be the notes from another lecture that he attended. Among these notes, he has written some ideas on how sickness works:

“sickness — vibrational problem…assume you are O.K. convey to them that they can go off to take care”.

If this is a lecture, I wonder how much of this he absorbs into his own real view of sickness: if sickness is simply a vibrational problem, I wonder how he is viewing the AIDS epidemic and his friends who have suffered from AIDS. This seems ostensibly plausible for him to adopt as he has many notes written in the notebook about existentialism and he clearly has an interest in the cosmic soul and its orientation.

Beyond sickness just being a vibrational problem, he begins to note different types of healing, such as distance healing from people who are alive and palm healing, which he describes as “using[?] palm over sick organ to burn off ki”. In addition to these healing methods, he is, once again, considering the role of food and cooking. Here, he meditates on the proper use of fire and cooking.

We are beginning to explicitly see how the notes in this notebook are all connected to one another: existentialism, recipes, the soul, AIDS, etc. Jim Fouratt must believe — or at least is very intrigued by the thought — that sickness goes deeper than a malfunction of the body, but the state of the soul and consumption also contribute. Thus, remedies from these outlets must be utilized to heal.

Shortly after those notes, it appears that Jim Fouratt may have spoken with or attended a talk by a Dr. Enlow, where he answered questions about the AIDS epidemic. From this event, Fouratt has notated two main points:

(1) We do have ample evidence that S.T.D are epidemic among gay men in large urban centres.

(2) Freedom of choice: chemically distorted self-loathing

Bathhouses are not the highest model of gay sexuality.

This is one of the most direct references to AIDS in the notebook. Here is where it is written that AIDS is unequivocally high amongst gay men and that its contraction may be a result of attendance at these bathhouses. Now, Jim must begin to reconcile the fact that the actions of the community are directly hurting itself, while dealing with the role that the greater society and culture plays in causing it, such as making gay men feel as though they can only exist freely and safely in the shadows of nightclubs and these bathhouses.

Soon after Jim faces the reality of how AIDS is spreading so quickly among gay men, he faces the reality of substance abuse among gay men and its relationship to AIDS. He considers the “sexual connotation of shooting up” in which he writes that nine percent of speed users of all active gay males have used riddles/niddles{?}. He then considers how this has contributed to recreational drug propaganda between anal intercoure and riddle/niddle use. An interesting line that he writes right below this is the fact that “compassion for strangers is lacking in IV drug use community”.

Right after this, we have an entry by Fouratt that appears to be the draft of a speech or a presentation to an organizational body:

Into this spirit of sister and brotherhood

I would like to speak on a few hard issues

the epidemic continues more and more people are becoming ill with other AIDS RELATED complex and full blown AIDS

the Administration

the governments election year rush to endorse and promote a recent virus discovery as the cause and there for [sic] the prerequisite for the development of a vacine [sic] - was dangerous had (?) a very critical effect on the AIDS problem:

the at risk community

feels the risk is over and are returning to business as usual -

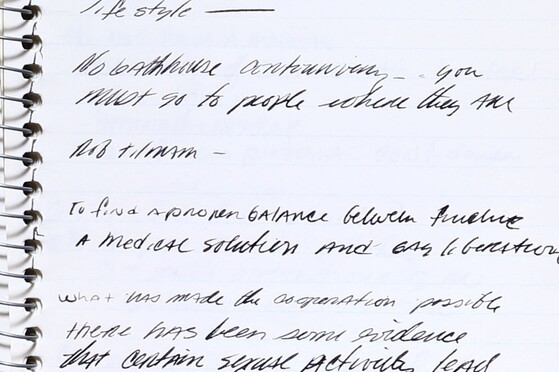

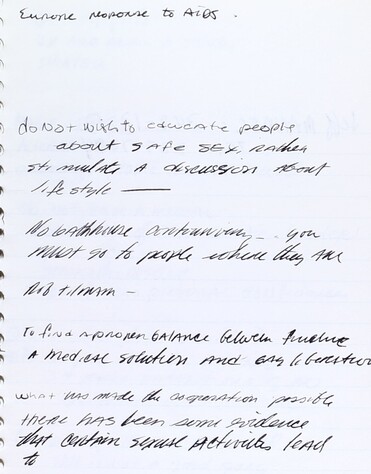

In Fouratt’s expedition to learn as much as he can about the AIDS epidemic, he looks across the Atlantic to Europe to get some insight as to how they, as a continent, were generally handling the spread of the disease throughout the population. In his search, he writes that Europe “does not wish to educate people about safe sex, rather simulate a discussion about lifestyle”.

So, he is thinking that, rather than trying to educate their queer population, they have been prioritizing discrimination and chalking up the spread of the disease to a lifestyle choice, as if it is an inevitability to being gay. This shows his regard for the way that other places handled the AIDS epidemic to try and learn from — even adopt, if efficacious — some of their practices to help the NYC queer population. While this shows his attempt to help, it highlights the failure of other places in company with the United States to do more to throughly help their vulnerable populations.

Fouratt also finds that there is no bathhouse controversy, as he writes that

you must go to people where they are

This could be taken in a couple of different ways. First of all, there is the literal sense that they are going to the bathhouses, where the people (gay men) may be contracting and spreading the disease. On the other hand, the side I am more inclined to believe that Fouratt meant, it may mean that one must meet people where they are, mentally and emotionally. So, without the shame of the boathouse culture — without the controversy surrounding it — one is able to truly meet these people where they are to try and educate and protect them.

Below this is where, debatably, the most powerful statement in this notebook can be found:

To find a proper balance between finding a medical solution and gay liberation

With this statement, he is epitomizing the struggle of the AIDS epidemic, both as a gay man and as a person trying to help stop the spread of the disease. Many of the things discussed in this notebook — sex, bathhouses, drugs, etc. — have simply become a part of the gay culture at the time. Though many have been found to be destructive, they were all the community had in the face of widespread discrimination and false information and fear. So, they clung onto them: bathhouses felt like safe-houses and poppers felt like pain-numbing medicine. These destructive entities became the subversive glue that was holding the community together, symbols of gay liberation. Fouratt understood that and did not want them to be taken away. On the other hand, he knew that these are the things taking the lives of so many queer people in the community, and more and more would be taken if intervention wasn’t taken. Thus, he searched far and wide for a solution that balanced these two interests, across oceans, in lectures, in existentialism, in cooking. Everything he did in regards to the AIDS epidemic for this end.

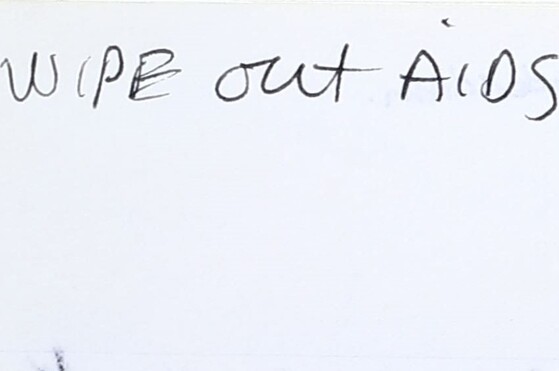

Toward the end of this notebook, we see a mostly blank page with one phrase at the top:

“WIPE OUT AIDS”

This became the name of an organization (now H.E.A.L.) he had a hand in founding after he co-founded the organization “Gay Liberation Front”. Organizational work toward the fight to end the AIDS epidemic and gay liberation became his legacy in activism and now hundreds of organizations for the rights, freedom, and advancement of queer people exist as a result of Jim Fouratt’s work.

His 1984 Notebook: Today

Jim Fouratt’s influence on the advancement of the gay liberation movement and the AIDS epidemic via his voice, his writing, and his advocation should not be discredited, and the entries of this notebook are prime examples of that. From the manner in which he thought about food to the manner in which he pondered the creation of the universe and our cosmic connections to one another, it becomes clear to see that he ate, lived, thought, and breathed these causes, and they still have not left his life all these years later. Without the pivotal force of Jim Fouratt and the percolating effects of his influence, who knows where these two causes would be today.

With that being said, it is of paramount importance that we — as a society — do not allow people and historical figures that have made positive impacts get off the hook or go without criticism for their problematic actions and the consequent damage that was done alongside the positives. As mentioned earlier, the LGBTQ+ community tends to be the group actively advancing the idea of respect and liberation for all people, regardless of any identity that they may possess. Though the LGBTQ+ community does, in fact, tend to guide the rest of society in the lane of respectful language and reference, it is noteworthy to note that even members of the LGBTQ+ do not always practice this. Jim Fouratt is, unfortunately, a quintessential example of this. Though a crusader for gay liberation and the AIDS epidemic, Jim Fouratt has actively thwarted the liberation cause for another demographic within the LGBTQ+ community: the trans community.

There have been mulitple occasions in which Jim Fouratt missteped in his discussion of the transgender community. He made many anti-trans comments in his time, such as saying that transition surgery is akin to “anti-gay reparative therapy” and calling transgender women misguided gay men who have underwent “surgical mutilations”. Jim Fouratt was not alone in his offensive and exclusionary language as a gay man. Many gay men of Jim Fouratt’s generation held a blind spot in their view of gay liberation coming in the form of anti-trans and misogynist rhetoric. So, though Jim Fouratt and other gay men who possess these derogatory views should be praised for their work in the advancement of gay men toward equality and liberation, it is essential to take off the rose-colored glasses and acknowledge the problematic side of their characters, which were implicit in their actions in the movement.

Thus, Jim Fouratt is a great example of this principle that must be kept in mind as we continue to reach back into history and analyze important and impactful figures with critical, contemporary perspectives. Just because a person has done a lot of good, it does not mean that they should be absolved for the bad that they have committed. And — within reason — the same principle must endure for the opposite: just because a figure has done a lot of bad, the good that has been performed should not be wholly ignored. And for this, Jim Fouratt is a prototypic.

Citations

“Ahead of Billboard Pride Fest, Activist Jim Fouratt Looks Back on Stonewall: ‘It Changed My Life’.” Billboard, 08 Aug. 2019, https://www.billboard.com/culture/pride/activist-jim-fouratt-stonewall-i….

“Jim Fouratt: A classic example of transphobia in older-generation gay men.” University of Michigan, 20 Jan. 2006, https://ai.eecs.umich.edu/people/conway/TS/Fouratt/Jim%20Fouratt.html.

“Nightlife Legend Jim Fouratt Talks What Really Happened at Stonewall and Birthing Danceteria.” Paper Magazine, 07 Apr. 2017, https://www.papermag.com/nightlife-legend-jim-fouratt-talks-what-really-….

![Fouratt, Jim [January 1994, Robert Giard Papers at The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library]](https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/cropped_image/public/screenshot_2022-07-08_at_4.20.20_pm.png?itok=ilUv4EVf)