The James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters was founded in 1941 by Carl Van Vechten as a memorial to Dr. James Weldon Johnson; the collection celebrates the accomplishments of African American writers and artists, beginning with those of the Harlem Renaissance. Grace Nail Johnson contributed her husband’s papers, leading the way for gifts from many of Doctor Johnsons’ friends and colleagues. A details description of the collections can be found here: The James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters.

The following essay by Bruce Kellner, Carl Van Vechten’s friend and the executor of the Van Vechten Trust, celebrates the Beinecke Library exhibition Living Portraits: Carl Van Vechten’s Color Photographs of African Americans, 1939-1964 and includes images featured in the exhibition. A PDF version of the essay is available here: Carl Van Vechten’s African America.

CARL VAN VECHTEN’S AFRICAN AMERICA

Forgive me for reading some of what I want to say about Carl Van Vechten. Talking off the cuff, it’s too easy to start rambling down Memory Lane and deter us, not only from questions and answers but from the libations on the other side of the library. Forgive me, too, for repeating some information from the brochure for this exhibition. I have been proselytizing for Carl Van Vechten’s work for over fifty years, and sometimes I run out of fresh fodder.

Last year, when Patricia Willis had his color slides digitalized for exhibition, just before she retired, she asked me to speak at the opening. Then renovations in the Beinecke delayed that for a year – and me too, so I was delighted when Nancy Kuhl reissued the invitation. I did my first research in the Yale Libraries over fifty years ago, and I’ve never had less than a good time.

Carl Van Vechten’s multiple careers – music critic, drama critic, literary critic, editor of arts journals, ballet afficionado, best-selling novelist, celebrity photographer, authority on cats, early white authority on African American culture, plus his reputation as a naughty boy about town, and a Darktown Strutter in Harlem during the Twenties, doomed him to be identified as a dilettante, and in some camps distrusted because of that. In many instances, however, he was only a friendly entrepreneur promoting the work of others, and he restored some delight to a worn-out epithet: long ago a dilettante was not a dabbler in the arts, a dilettante was a lover of the arts.

Just about a hundred years ago, Van Vechten was already writing enthusiastically, first as assistant music critic for the New York Times and then in various periodicals, about the music of Igor Stravinsky and Erik Satie, and the early operas of Richard Strauss, when few others seemed to be listening. A generation later he was first to champion George Gershwin’s music, and in between he was the first person to advocate integrated musical scores by serious composers for the movies. Also, Van Vechten was America’s first dance critic, writing before anybody else did about Isadora Duncan and Anna Pavlova and Vaslav Nijinsky. Van Vechten was early to proselytize for the experimental writings of Gertrude Stein, and he was among the first to resuscitate Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, at a time when you could still buy a second-hand copy of that failed masterpiece in a used bookshop for fifty cents. Van Vechten engineered into print the first books of poems by Langston Hughes and Wallace Stevens. His book about cats, The Tiger in the House, was neither the first nor the last word on the subject, but it has proven the longest-lasting, never having gone out of print in eighty-nine years.

More pertinent to our gathering this afternoon, Van Vechten championed African American culture in all its facets, but to grasp a sense of his commitment requires a little background. As a student at the University of Chicago, he’d been regularly exposed to Negro spirituals and gospel music through church services he attended with his fraternity’s African American cook. And he fell in love with black ragtime and jazz and entertainers in black saloons and stage shows, and as a reporter on the Chicago American and then the New York Times, he wrote about them whenever he got the chance. Then, in 1917 as an established music critic, with three books of essays to his credit, he insisted – in print and more than once – that jazz and ragtime were the only authentic American music.

His seven best-selling novels do not seem so decadent now, but they’re still diverting, largely about what he called “the splendid, drunken twenties.” The books are stagey and arch and funny, and they’re all about sex, but they’re not sexy. One of them is all about racism, but it’s not racist, although that word now carries implications that went unrecognized because of white ignorance at the time. Also, that novel is not stagey or arch or funny, and today it suffers from Van Vechten’s earnestness than it does from its depiction of Harlem’s seamy side.

Now, before the Twenties, Harlem might as well have been in quarantine for most white Americans, with an unmarked social barrier at 125th Street, white to the south, black to the north. But Van Vechten was already familiar with its after-hours cabaret life and its jazz musicians and performers, a holdover interest from his Chicago days. By the middle of the Twenties, just at the time Harlem had declared the itself the “Mecca of the New Negro,” Van Vechten had come to know something of its intellectual life as well – its aspiring poets and novelists, including some influential members of the N.A.A.C.P. White patronage at the time was rare, so Van Vechten was warmly welcomed into their company because he had been writing a series of revelatory essays published in wide-circulation white periodicals, about Negro spirituals, blues, work songs, singers, dancers, and other entertainers, musical comedies and revues, and the desperate need for a serious Negro theater company, because black playwrights could not get produced on Broadway – these were all unknown subjects to most white readers – and in turn Van Vechten had become a friendly aquaintance of a number of African-Americans, even an intimate acquaintance of some.

And then he transformed everything he knew into a compassionate novel about life in Harlem in all of its aspects. He called it Nigger Heaven. Some of his friends – black and white alike – urged him not to, although the title had long been a common slang expression for the balcony in white theaters where African Americans were forced to sit. He never regretted his use of the phrase as his title; he insisted on its use in subsequent editions, even a quarter of a century later when a reprint house wanted to issue it under another title. He refused.

Van Vechten’s novel has been often condemned as vulgar and exploitative and an endorsement of primitivism, sometimes just because of the title, even though Van Vechten claimed that he intended his use to be ironic, since the offensive word was employed freely and even affectionately among African Americans themselves. Many readers may not have got far enough into the novel to read Van Vechten’s explanatory footnote, declaring that the word was fiercely resented in the mouth of a white person, which most white people simply did not know. Or to have read far enough to hear a young prostitute exclaim in delight with the phrase to describe Harlem’s glamour not its squalor during the Twenties, or to hear the novel’s protagonist, a young black writer, cry out in despair:

“Nigger Heaven! That’s what Harlem is. We sit in our places in the gallery of this New York theatre and watch the white world sitting down below in the good seats in the orchestra. Occasionally they turn their faces up towards us, … . . to laugh or sneer, but they never beckon.”

About two-thirds of the novel are devoted to serious discussions of Harlem’s color line, its sociology, its inequalities in housing and income, its social and economic segregation, the struggle of its young, educated middle class to succeed, and also to an anemic love affair, as vapid as it is sexless, between a sweet librarian and the aspiring writer I just quoted. (In Van Vechten’s other novels, his nice characters are never very interesting and usually dim or boring; his naughty characters are always interesting, glamorous and seductive, and they get all the good lines. But his other novels are white comedies of manners, and Nigger Heaven is a largely humorless, polemical tract.) The third third of the book does take place in seedy speakeasies and steamy bedrooms, with accounts of the numbers racket, pimps, whores, parties, and cabarets, the effervescent street life, all of which were certainly part of the scene in Harlem at the time. Some black Americans, especially of the older generation , would have preferred not to divulge any sensational stuff to white Americans, believing instead that racial injustice could only be overcome by showing Harlem’s best side, not its worst. Their high hopes for a literary renaissance did not include that third third in Van Vechten’s novel. The press was mixed: mostly positive from white reviewers, and from their incredulous white readers who had no idea what had been going on in Harlem; mostly negative (and hostile) from black reviewers, and from their black readers who knew Harlem all too well, and didn’t need some ofay writer to tell them about it.

Van Vechten lost only poet Countee Cullen among the black friends he’d made before the novel was published. Langston Hughes, for example, was his most intimate friend among African Americans for forty years, actress Ethel Waters nearly as long. There were also close friendships – as their letters attest, most of them now here in the Beinecke – with poet James Weldon Johnson, actor Paul Robeson, dancer Bill Bojangles Robinson, gadfly of the N.A.A.C.P. Walter White, novelists Nella Larsen and Rudolph Fisher, and Zora Neale Hurston who claimed, ”If Carl Van Vechten were a people instead of a person, I would then say, ‘These are my people.’” She called him a “Negrotarian.”

Van Vechten was surely responsible for serious white interest in new African-American literature during the Twenties because of his proselytizing, although readers constitute a minority opinion because even best-sellers don’t rack up a lot of points for anything except among other readers. Moreover, it is not during the Negro Renaissance, as it was then called, but largely in retrospect that black writers have secured their footholds on Parnassus. Some of Langston Hughes’s poems during the Twenties, for instance, were fiercely resented by genteel African Americans who called themselves “colored people,” not Negroes; they preferred Countee Cullen’s poems, imitative of John Keats; the novels of Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larsen had little success until long after their deaths in obscurity. Novels by Rudolph Fisher and Claude McKay and Wallace Thurman were forgotten almost as quickly as they were published. Not one book by a black writer ever made it to a best-seller list during the Twenties and Thirties, and few made it to a second printing. Van Vechten’s novel did. Fourteen printings in the first year.

But the Harlem Renaissance of the Jazz Age was fueled not by literature, although it has been romanticized to have done so. The Jazz Age was fueled by liquor, and the emerging voices of black artists and writers and especially entertainers merely coincided with a sudden urge to start drinking very heavily not long after Prohibition went into effect in 1919, and speakeasies flourished all over New York, black and white alike, although the white ones closed about one a. m. and many of the black ones were open until dawn. I hasten to add that black customers could not patronize white clubs although white costumers overran after-hours black clubs and even Jim-Crowed out African Americans. Oh, it was a strange time, and only vaguely at this remove can we approximate the level of concentrated drinking or – more tellingly for our purposes this afternoon – the racial climate in this country then. Carl Van Vechten and his wife, the Russian actress Fania Marinoff, certainly scandalized the neighbors by regularly including African American friends for dinner or parties in their West 55th Street apartment, and sometimes, if the party was big enough, it got written up routinely in the gossip columns of Harlem’s newspapers. Walter White called the Van Vechtens’ apartment “the mid-town office of the N.A.A.C. P.”

But Van Vechten gets credit or censure for popularizing black cabaret and speakeasy life as word got around about that racy third of Nigger Heaven. He served as an escort, not only on paper but in person, for slumming white thrill-seekers in search of Harlem’s pleasures. The year before his novel was published, Time Magazine sneered with racist innuendo that “sullen-mouthed, silky-haired author Van Vechten has been playing with Negroes lately, writing prefaces for their poems, having them around the house, going to Harlem.” The year after, nearly everybody else seemed to be going to Harlem too.

Van Vechten himself was drunk much of the time and right around the clock. (Of course he wasn’t alone; drinking became a patriotic duty during the Twenties.) In the daybooks that he kept then, one reads “Up at 8.30 with a hangover.” “Up at 7.30 with a hangover.” “Up at 9.00 with a hangover.” And sometimes entries like that came three or four days in a row. “If I don’t stop drinking, probably I’m going to blow up,” he wrote in 1928, right in the middle of what was being called a “Negro Renaissance,” during which Van Vechten misbehaved outrageously, careening from one Harlem night spot to another, dancing with drag queens in speakeasies, going on after-hours pub crawls, or hanging out at rent parties and in buffet flats. By that time, white Manhattan needed no urging to flock to black Manhattan.

Well, all that brought a lot of business into Harlem; it also perpetuated a lot of racial stereotypes on the basis of a small percentage of the African American community. So the benefits and limitations of Van Vechten’s influence remain open questions, and the ambivalence among scholars – black and white alike – is understandable.

Then, just before the stock market crashed in 1929 and sent people swan-diving through their Wall Street windows, or just sliding downhill toward the Depression, Van Vechten inherited a lot of money when his brother died, and when the Twenties died the following year, he withdrew from public life, he sobered up, he swore off parties, he gave up his Harlem forays since Harlem began to collapse in a hurry anyway, he forsook writing, which he’d always found a chore, and after two more books he turned to photography. This hobby produced about twenty thousand photographs, to include a remarkable catalog of celebrated twentieth century figures. With his African-American subjects, the hobby grew into a commitment.

For next thirty-two years, until his death in 1964, Van Vechten made photographs to add to this remarkable archive, and he got his subjects early as well as late: Singer Lena Horne at the age of eighteen or so, fresh from the chorus line at the Cotton Club, and he finally got the most powerful figure in the N.A.A.C.P., W. E. B. DuBois, at the age of seventy-eight, by which time Van Vechten had decided to try to photograph every established or promising African American he could cajole to sit for him.

Over the years, some refused – for example, actor Sidney Poitier, political activist Louise Thompson Patterson, novelist Ralph Ellison, composer Duke Ellington. Maybe they were distrustful of a white man who still had a bad reputation as an ofay playboy in Harlem’s speakeasies during the Twenties, but most African Americans readily agreed to be photographed, certainly those Van Vechten knew socially, and they in turn could lead him to other potential subjects. One of his old buddies in Harlem’s homosexual community, jazz pianist Porter Grainger, brought him Bessie Smith, and Bessie Smith in a roundabout way gave him entree to Billie Holiday, and in between those two colossal figures he photographed Ella Fitzgerald. Pearl Bailey got him Diahann Carroll and Alvin Ailey when they were still in their teens and appearing with her on Broadway. Langton Hughes brought Van Vechten a number of writers: James Baldwin, Amiri Baraka, Claude McKay, John A. Williams, Ann Petry, Gwendolyn Brooks, Margaret Walker; also dancers Katherine Dunham and Arthur Mitchell, both of whom went on to found distinguished dance companies; Harry Belafonte got him Sammy Davis, Jr. Bojangles got him Cab Calloway. Richard Wright brought him Chester Himes. Walter White brought him Marian Anderson. William Warfield brought him Leontyne Price. Somebody brought him prizefighter Joe Louis, educator Mary McLeod Bethune, Nobel Peace Prize diplomat Ralph Bunche, and gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. It was a network, and the resulting photographic catalog is impressive, but that’s enough name-dropping. The Beinecke’s exhibition is sufficiently persuasive without any help from me.

In the beginning, with black and white photography, he liked to experiment with over- and under-developing, pulling, and burning, and double-printing, but he rarely retouched his work or cropped it. Every blemish, frown, and wrinkle stood in clear view, and every frame made a composition. Unlike most photographers, he made finished prints of most of his exposures. If we recall Yousef Karsh’s photograph of Ernest Hemingway, or Richard Avedon’s photograph of Andy Warhol, or Annie Liebowitz’s photograph of Meryl Streep, we usually know of a single image in each case. Contrarily, there are a lot of Van Vechten photographs of the same subject. Fifty or more of Eugene O’Neill, three times that many of Gertrude Stein, about a thousand each of dancers Alicia Markova and Hugh Laing. Zora Neale Hurston – the subject most often requested for reproduction – is represented by a dozen poses from three sittings, has been endlessly reproduced in books and periodicals and on posters and postcards and websites, including one on a United States postage stamp, now that she has become a cottage industry.

The variety, for all its interest, leads to a good deal of unevenness. Van Vechten claimed he threw out “anything that isn’t perfection”; even so, there are better and worse portraits of nearly every subject in his catalog. As for that, there are better and worse prints of the same photograph, because he could be his own worst enemy in the darkroom, failing to wash his prints sufficiently free of their chemicals, because he was so eager to share them with his friends.He never photographed anybody he didn’t want to photograph, he never took commissions, and he never sold a photograph. He didn’t need the money, and he preferred the freedom. The subjects got the photographs that he liked, not necessarily the ones they liked. “I don’t even ask them,” he said, “and if I were paid I would have to submit to some subject’s demands.”

But Van Vechten never seems to have thought of his work in commercial terms anyway. At the time he died, photography as an art form had a comparatively modest following anyway and few collectors; not many of his photographs had been reproduced, and they’d rarely been exhibited, although he’d included among his subjects a remarkable roster of celebrities, everybody from Georgia O’Keeffe to Marlon Brando to Dave Brubeck, but I’m not going to drop any more names or we will be here all night.

Van Vechten’s early interest in African American arts and letters gave him his most enduring subject. It may be that the availability of color film in 1939 motivated his turning away from the glamorous chiaroscuro of the Thirties to a more straight-forward documentary approach of the Forties and Fifties and a concentration on African American subjects. The change did not alter the essential and unmistakable elements in a Van Vechten photograph, however. A Van Vechten photograph – good or bad – looks like a “Van Vechten.”

In the beginning, he was heavily influenced by Art Deco, an intense contrast between light and dark, often theatrical, where the actual lighting can be as fierce as fire or dark enough to lose half his subject’s face in shadows. Later on, the photographs became more straight-forward, and, as he called them, “documents,” but they’re often very busy ones, with a profusion of pattern and color, sometimes deliberately jarring, as unexpected as they are riotous, almost invariably a reflection of the subject, not only in the Kodachromes but in black and white, because the suggestion of color through textures and contrasts in patterns, he believed, had an influence over the composition. He favored profiles, pensive stares, even insolence, and he did not encourage “posing.” No mugging, please, no camping for the camera. Smiles are rare, in part because he often commanded you to “stop smiling.” The results followed very quickly: many copies of the black and white photographs, large portraits and endless postcards, all stamped with his embosser, all intended as gifts to the subjects and to his friends and for his collections in several university libraries and museums. But few of the subjects saw their Kodachrome versions, certainly not in the wonderful, digital prints in this exhibition.

Van Vechten himself never saw them in this format. He rarely had slides reproduced as photographs. He preferred them blown up to poster-size on a movie screen. And he used to give slide shows for his friends, as few as two or as many as he could crowd in, ten or twelve people maybe. Folding chairs would be set up in the big foyers of two successive Central Park West apartments, and we’d get a planned program. Sometimes we got a little bit of this person and a little bit of that one, but mostly there was some theme to the evening’s gathering: dancers, actors, literary figures, maybe a single ballet – like Anthony Tudor’s Lilac Garden which he’d photographed al fresco on a friend’s farm in Connecticut. I remember an evening devoted to his slides of the Stage Door Canteen, where he was a busboy captain for nearly three years and never once missed his shift, to serve flocks of on-site soldiers and sailors who’d come there to have a good time while Broadway stars entertained them. Once we saw the 1939 World’s Fair – Van Vechten’s first color subject because that was the year that Kodachrome slides first became available to amateur photographers. And more than once we saw a selection of his slides of African-American subjects, because preserving a record of black arts and letters – not just his own photographs but the photographs by others, and books and manuscripts and programs and periodicals and newspaper clippings, and soliciting the manuscripts and correspondence of various black writers, became Van Vechten’s passion. They offered a sturdy foundation for the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Negro Arts and Letters, now here in the Beinecke at Yale, which Carl Van Vechten founded in 1941 and continued to support until his death – and after, because all income from fees and royalties collected for permission to reproduce his photographs or reprint his writings goes to the Johnson Collection.

(James Weldon Johnson – a figure sometimes overlooked because of his early death – deserves a footnote here. He was a poet, novelist, historian, politician, peerless envoy between the races, field secretary to the N.A.A.C.P, and arguably as powerful a figure in black culture as any other in the last century. Oh, yes, and he wrote the African American National Anthem, “Lift Up Your Voice and Sing.” He and Van Vechten had been each other’s literary executor, confidante, and best friend. Johnson himself did not live long enough to join the ranks of subjects among Van Vechten’s color slides.)

Those slide shows, by the way, could go for on a long time – or not. If the audience didn’t ooh and aah enough to please the maestro, he’d call it quits, not petulant but indifferent. Short show that night.

Somebody said that “Carlo” – as everybody called him – looked in old age like a werewolf, and when you got a look at his truly alarming buck teeth, he looked like a young walrus. ”Really, those teeth,” Mabel Dodge Luhan said, “they seem to have a life of their own apart from the rest of him.” And then he stared – rudely. He barked a lot too, especially when he was enthusiastic. Woof! Woof! During the Twenties he liked to bite people. Oh, not enough to draw blood, just an affectionate nibble on an earlobe or a finger, or he’d drop to his knees and pretend to chow down on somebody’s ankle. He combed his thinning white hair forward into bangs. (In 2009, lots of young men and even middle-aged ones, if they’ve got the hair for it, wear bangs; Carlo started that back in 1951, over a decade before the Beatles turned up.) Let me tell you, on the street, people turned and gaped. They’d been turning to gape over something or other ever since 1909 when Carlo sported the first wrist- watch in New York. He’d brought it back with him from France after his season there as Paris correspondent for the New York Times. His undulating wobble was distinctive, and his rings and bracelets raised some eyebrows, because men did not wear jewelry, and then there were those teeth.

When I knew him, late in his life, he wore spiffy jackets tailored without lapels, his multi- colored shirts and his ties deliberately clashed, and his suspenders, embroidered with naked ladies or whole bouquets of flowers, held his beltless trousers up under his armpits because he’d grown ample. But a lot of the time he worked in just his pajamas and elaborate dressing gowns, greeting strangers and friends alike in such homey garb. At the age of seventy-seven he had to replace one of those conspicuous teeth. Momentarily he’d thought about having them both out and a new and improved version installed, but then he decided that nobody would recognize him, and he doted on being recognized. At an outdoor summer concert around that time, two teeny-boppers came up to ask for his authograph. “Do you know who I am?” he asked, staring balefully and then signing their programs with a flourish. “Well, you never can tell,” one of them confessed, “you sure look like you ought to be somebody.”

A friend once confessed that he found Carl Van Vechten “mysterious.” “I am the least mysterious man in the world,” he retorted. “My life is an open book and everybody knows how I feel on practically any subject.” Elsewhere he said, “I never argue. Arguing never gets anybody anywhere. I state my opinion and you can take it or leave it.” But he liked to quote Walt Whitman: “Do I contradict myself? Very well, I contradict myself.”

He looked not quite real, simultaneously aged and ageless, pink as a baby, but drooping like cut flowers on their way out, and at eighty-four he had no wrinkles. Still photographing at that age, he stood like Stonehenge above his camera on its easel, still with that penetrating stare, while he waited for the “exact second.” He believed in it entirely, although there were happy accidents too, and more than a few that were not. He was an amateur, but in the old-fashioned sense of the word: somebody who really loved what he was doing.

Today the walls of the Beinecke attest arguably to Carl Van Vechten’s greatest legacy, through his photographs that he insisted were “intended primarily as documents, but I see no reason why documents can’t be beautiful.”

Bruce Kellner

29 April 2009

Copyright©2009 Bruce Kellner; a PDF version of this essay is available here: Carl Van Vechten’s African America

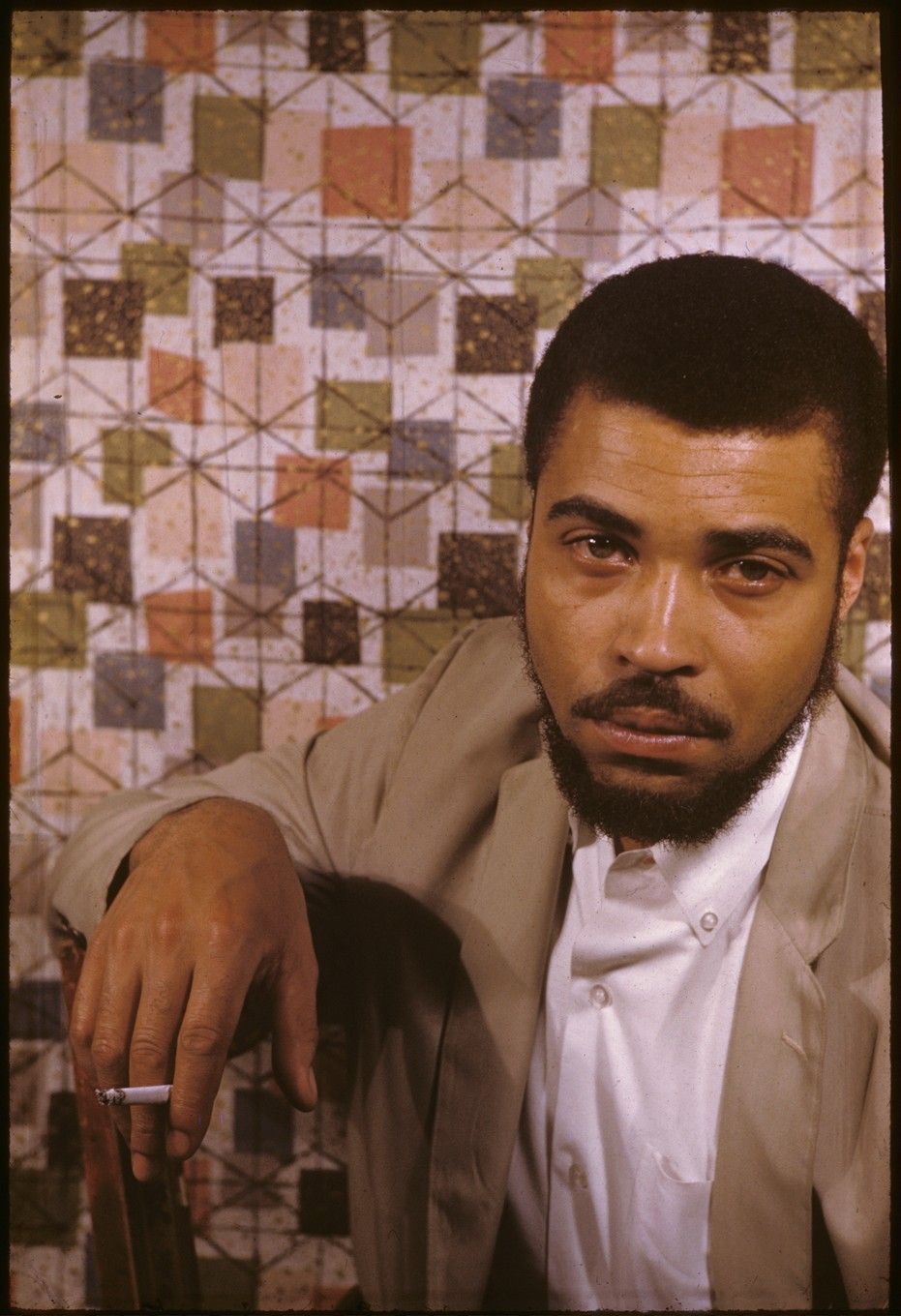

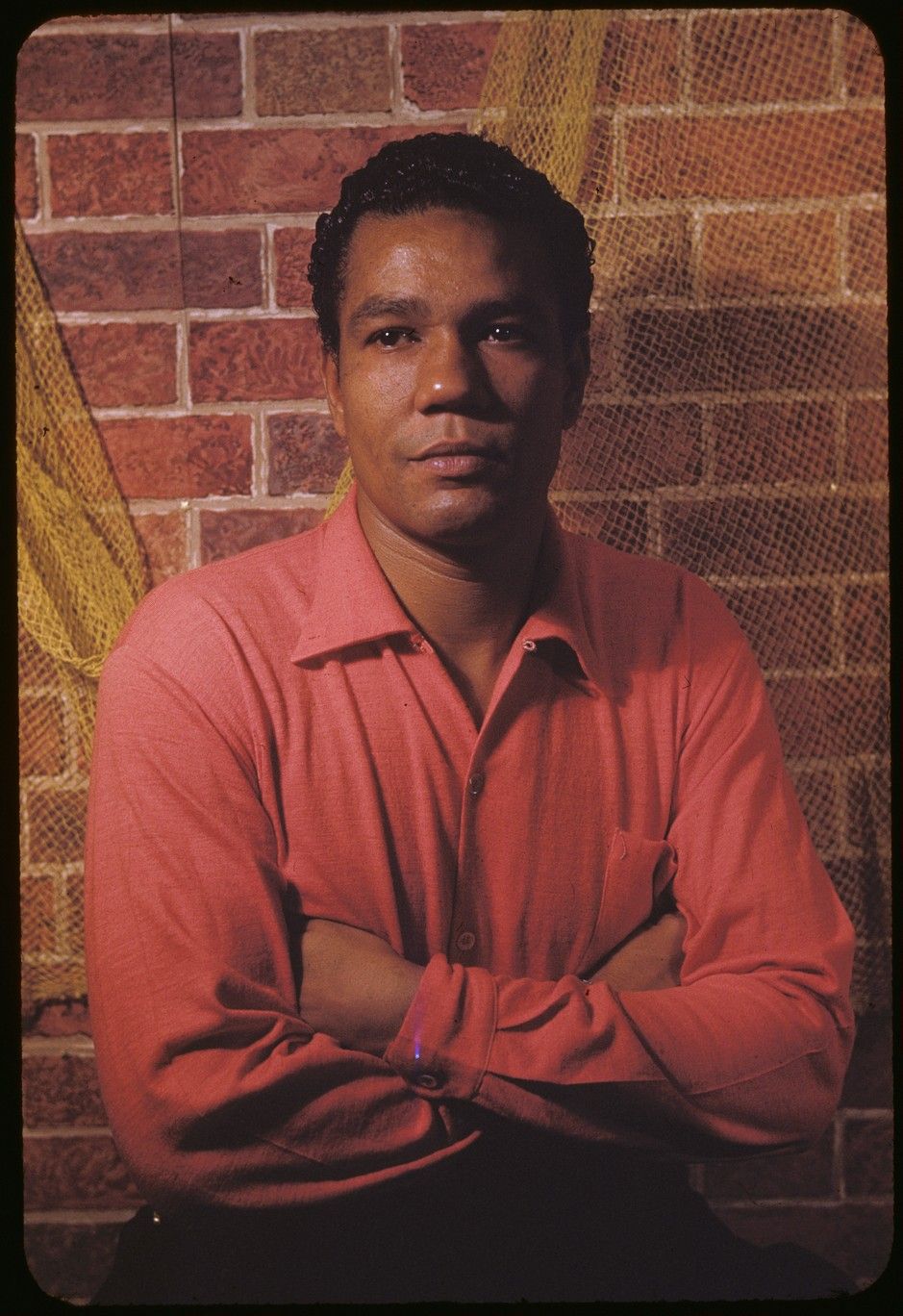

Photographs by Carl Van Vechten: Carl Van Vechten, 1951; Billie Holliday, 1946; Pearl Bailey, 1946; Reri Gist, 1958; Frederick O’Neal, 1958; W.E.B. DuBois, 1946; Gerri Major, 1951; Leontyne Price, 1954; Marilyn Horne, 1961; Eartha Kitt, 1954; James Earl Jones, 1961; Dizzy Gillespie, 1955; Diana Sands, 1961; Everett Lee, 1947 ; Roy Wilkins, 1958; Althea Gibson, 1958 ; Clayton Corbin, 1954; Robert McFerrin, 1955; Carl Van Vechten and Diahann Carroll, 1945.

Photographs by Carl Van Vechten are used with permission of the Van Vechten Trust; the permission of the Trust is required to publish Van Vechten photographs in any format. To contact the Trust email: Van Vechten Trust.

Bruce Kellner is Professor Emeritus of English at Millersville University and the author and editor of several books about literature and art. Among them are books about friend and mentor Carl Van Vechten, including Letters of Carl Van Vechten, The Splendid Drunken Twenties: Selections from the Daybooks, 1922-1930, and the seminal biography Carl Van Vechten and the Irreverent Decades. He is also the author of The Harlem Renaissance: A Historical Dictionary of the Era and books about Ralph Barton, Charles Demuth, Gertrude Stein, and Donald Windham, and a memoir Kiss Me Again: An Invitation to a Group of Noble Dames.