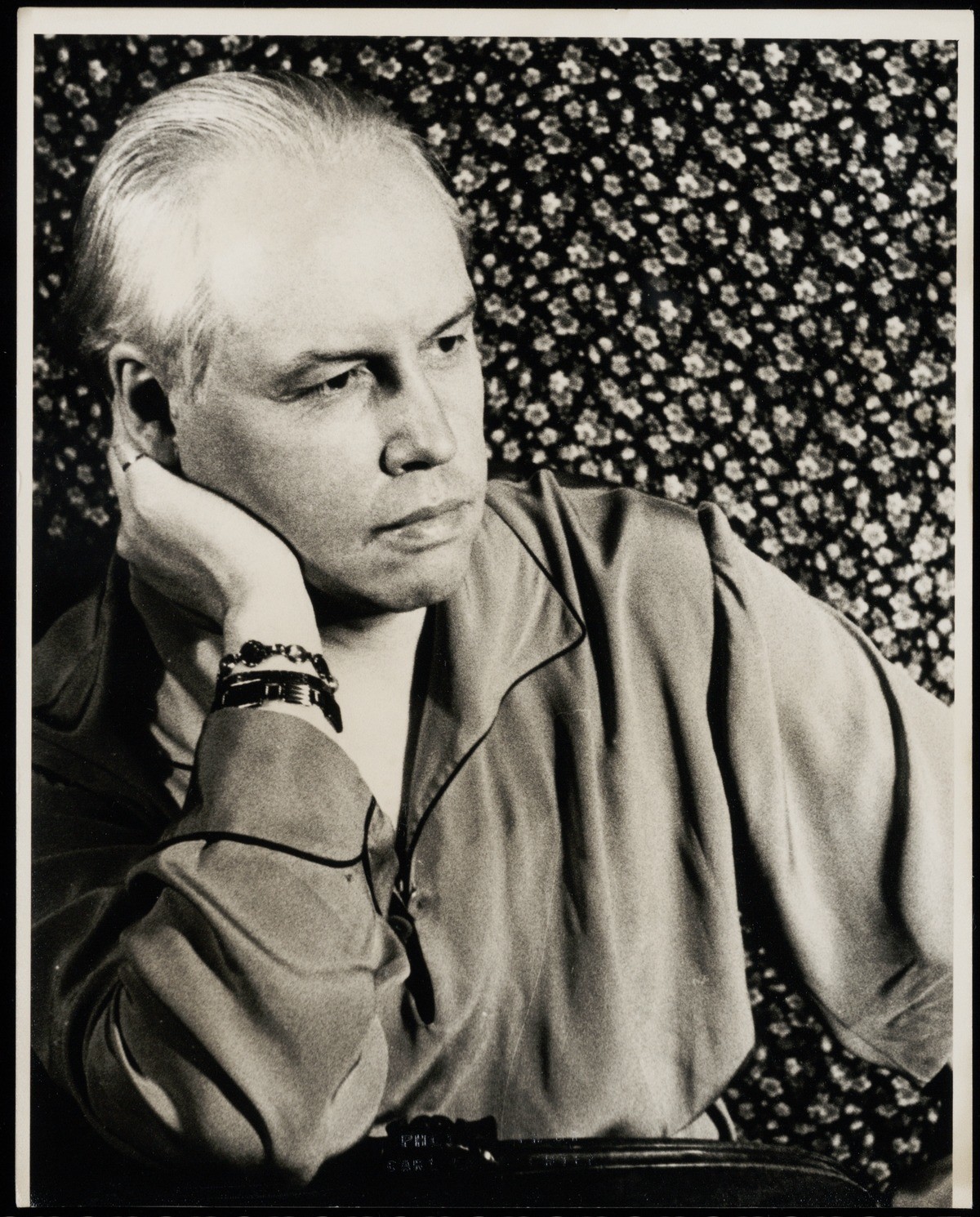

Emily Bernard will give a talk on Carl Van Vechten as part of the Mondays at Beinecke series at 4pm on January 23.

Literary historian and cultural commentator Emily Bernard has powerfully called the title of Carl Van Vechten’s novel Nigger Heaven a “wound.” And yet Bernard has also written compellingly about this novel, its reception, and her own experience teaching it and other appearances of the word “nigger.” In an essay titled “Teaching the N-Word,” Bernard narrates both her own and her students’ difficulty with the word: both to say it and to avoid saying it vest the word with power; both to say it and to avoid saying it mark the speaker’s relationship to the word and its history. In her study of Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance, Bernard writes, “To experience the wound of nigger is to be human, and a living repository of American history” (186).

Our aim in planning Gather Out of Star-Dust was to showcase Beinecke’s holdings from the Harlem Renaissance, in all their breadth, diversity, and complexity. Knowing that this is a period about which many thousands of pages have been written—indeed, a period about which scholars cannot agree on a name, let alone countless other aspects—we wanted to make the exhibition about, first and foremost, the original materials that inspired such a response. Of course, curation is an editorial project, and our decisions about what to include and what to omit would in themselves convey a stance.

We chose to include references to the publication and reception of Van Vechten’s novel because, from the standpoint of an attempt to faithfully convey the history of this period, it seemed impossible to gloss over the book. When the novel was published in 1926, it sold over 100,000 copies in just a few months, while also adding fuel to contemporary debates over the portrayal of African American life. W. E. B. Du Bois, anticipating Bernard’s use of “wound,” called the novel “a blow in the face.” James Weldon Johnson, on the other hand, defended it, urging readers to see beyond its title. The editors of Fire!!, including Wallace Thurman and Langston Hughes, also championed the novel.

We recognize the good reasons that exist to avoid repeating or endorsing the mistakes of the past, whether those of Van Vechten or Langston Hughes, who regretted his title “Fine Clothes to the Jew” within years of that volume’s publication. (The title, a line from one of the poems in the volume, refers to the common practice of pawning one’s Sunday best clothes in order to make ends meet through the week.) Showing these materials risks pain, misunderstanding, and recirculation of the dynamics of power and violence their uses originally represented. Bernard writes of having avoided teaching Van Vechten’s novel: “I could not get past specific images: a student at the checkout desk at a bookstore or a library, the title begging to be called out by anyone, with any kind of motive. Then there was the classroom to consider, and what the repetition of the word nigger would recall for each student, whatever his or her race” (186).

A passerby seeing a student reading the novel—which remains in print—in Bass Library or elsewhere might have little context for its appearance. Placing the novel inside Beinecke Library’s marble walls, under glass, offers the opportunity to give it appropriate context; at the same time, we want to avoid the novel and its language as wholly a relic of a past now happily gone forever.

Our purpose is to show the novel, and all of the material in the exhibition, not only to illustrate the past, but also to illuminate the present in the service of the future. Many of the questions driving the reception of the novel remain very much with us—not only who can use a single inflammatory word, but also, who is authorized to present black life in art? Who is the audience for that art? And what motivates both artist and audience? Asking these questions may mean that we probe painful places, but we hope that the discussion brings greater understanding.

-Melissa Barton, Curator of Drama and Prose

Yale Collection of American Literature and The James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters

Works Cited

Emily Bernard. Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance: A Portrait in Black and White. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

—-. “Teaching the N-Word.” The American Scholar Autumn 2005. https://theamericanscholar.org/teaching-the-n-word/