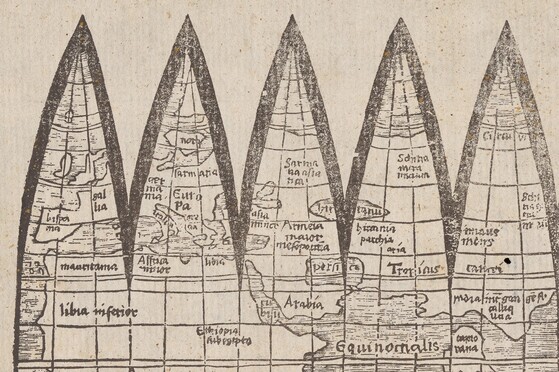

Above: Detail, GEN MSS 1486. Globe gore forgery after Martin Waldseemüller.

With early maps, forgery continues to consistently pose a problem because they carry such symbolic weight, thus pushing their prices increasingly higher. Luckily, science has played an outsized role in detecting these forgeries, and the Yale Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (YIPCH) has conducted several experiments that not only determine when, but also how maps were made. For example, we use a test that determines from which animal skins the parchment in our portolan charts were made. Most were made of calfskin or sheepskin, as expected, but the one by Judah Ben Zara in Galilee was made on goatskin, likely reflecting the paucity of calfskin in Palestine.

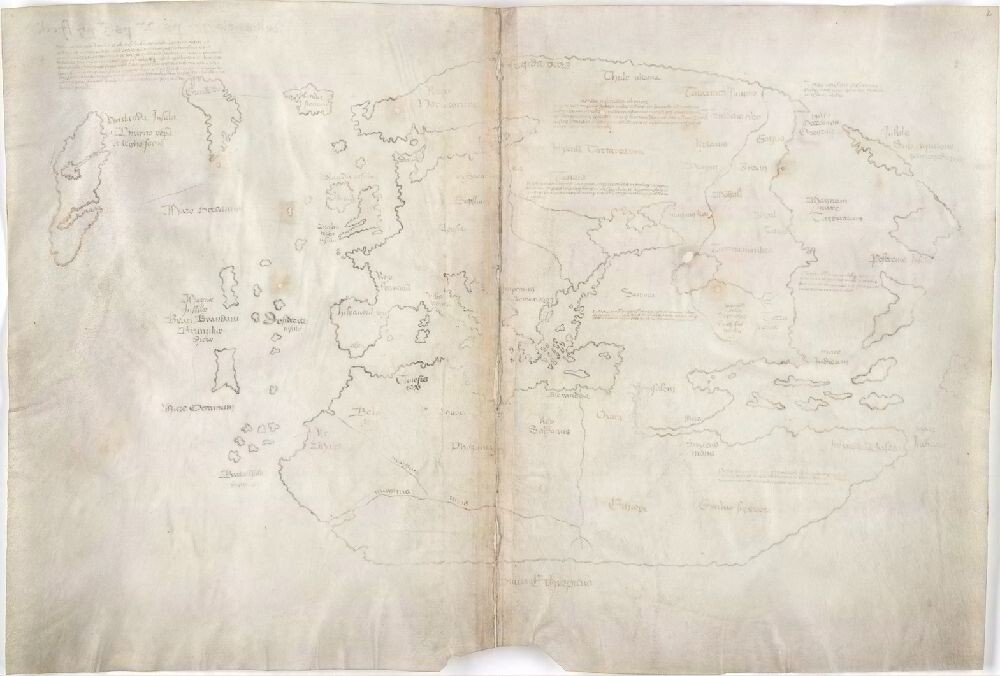

Above: The Vinland Map. Beinecke MS 350A.

The most famous map forgery is certainly the Vinland Map, which Paul Mellon gave to Yale in 1965. The map purports to show Viking settlements on Newfoundland and, if genuine, would be the first and only cartographic representation of the Viking discovery of the New World. Interestingly, archeologists had proven that, sometime in the eleventh century, Vikings had a community at L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada, so there is no doubt that Vikings were the first Europeans to establish settlements in the Americas. Yale’s announcement of the map stirred immediate controversy because it seemed to slight the role of Christopher Columbus and, by extension, to dismiss the Italian-American place in America’s Europeanization.

Early analysis by Walter McCrone in 1972 proved that the ink used to draw the map was a modern type that contained a manufactured form of titanium dioxide. Carbon dating placed the parchment in the fifteenth century, and later testing has shown that the leaves were taken from another book, also in the Beinecke Library, the Speculum historiale of Vincent of Beauvais (Beinecke MS 350). Recent testing by YIPCH has shown that the ink containing titanium dioxide is not just in the samples taken by Walter McCrone, but everywhere there is ink on the manuscript. We have no doubt the forger copied his or her map onto medieval parchment, but using modern inks. Interestingly, John Paul Floyd has independently discovered that the forger’s model for the map was an eighteenth-century hand-drawn facsimile published in 1783 of Andrea Bianco’s 1436 world map rather than Andrea Bianco’s map itself, as early historians had previously thought. This means the map cannot be dated before 1783 (the facsimile’s date of publication).

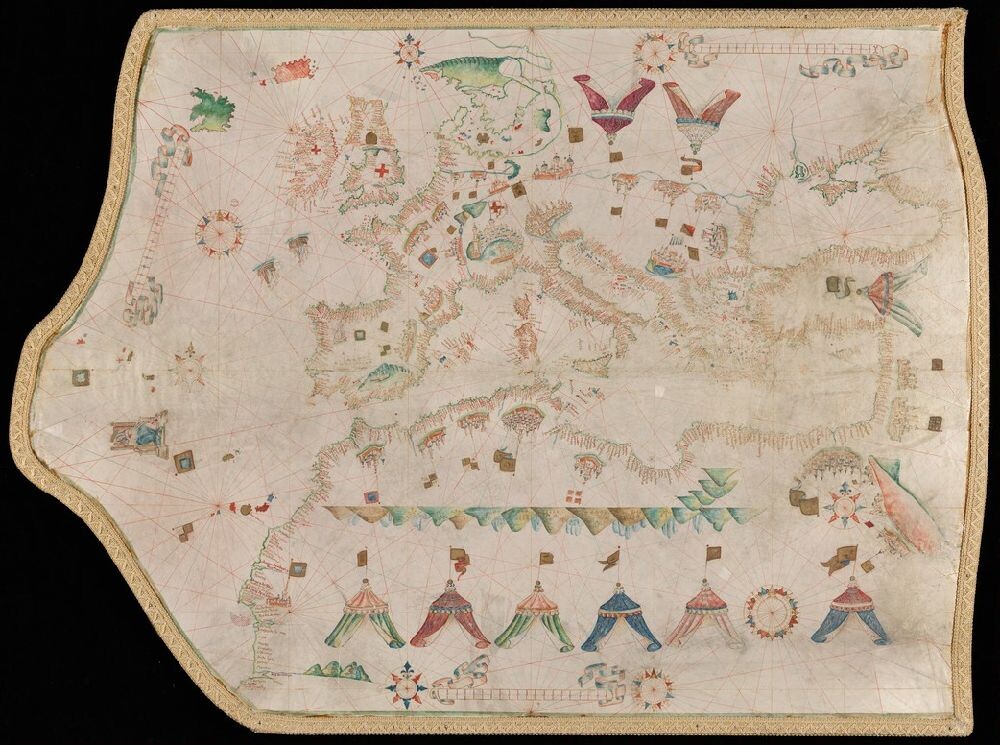

Above: Forged Maggiolo portolan chart. Art Storage 1019.

Some recent fakes shown in this case confirm that forgery is still practiced, likely as a way to make money from gullible investors. The Maggiolo portolan shown here is a fake modeled on the real Maggiolo portolan—also in Yale’s collections—which is displayed in facsimile beside it. Carbon dating revealed its parchment to have been produced in the 1950s. Another recent forgery exhibited is the Waldseemüller globe gores. These were printed on a single sheet in order to be cut out and shaped into a globe. The paper would have been glued onto a globe and covered in varnish for protection. The gores are valuable not only because of their extreme rarity (only six copies survive), but also because they are the first cartographic survival on which the American continents are labeled as “America.” Before it was discovered to be a forgery, in 2019 the Waldseemüller gores were estimated to bring in from $800,000 to $1,200,000 at auction. However, sharp-eyed cartographers noticed that the pictures in the auction catalogue showed that a small shadow left when making a repair to the paper was actually printed onto the paper, indicating that the gore had been made from a photograph of the original (at the Bell Library in Wisconsin). The item was removed from sale and acquired by the Beinecke Library for study purposes.

Forgeries are not just harmful because they con buyers; they also can distort the historical record. The Vinland Map, for example, has muddied the waters since its discovery, even though Yale itself announced that it was a forgery in 1973. Because controversy around the map’s authenticity continued to swirl, careful writers note that its authenticity is doubtful, but they still include the map in their study just in case it might be real. We hope that recent work done by YIPCH will put the question to rest and, toward that end, a symposium on October 10, 2022, at the Beinecke Library is intended to bring together historians, such as John Paul Floyd, and scientists to discuss the collaborative nature of their work and why continued testing, which provides new scientific data, is so important to historians of cartography.

Featured Objects:

Facsimile from C13a 783f, Saggio sulla nautica antica de’ Veneziani, con una illustrazione d’alcune carte idrografiche antiche della Biblioteca di S. Marco, che dimostrano l’isole Antille prima della scoperta di Cristoforo Colombo; di Vincenzio Formaleoni.

Beinecke MS 350A The Vinland Map

Beinecke MS 350 Tartar Relation

Art Storage 1019 Portolan chart forgery after the work of Vesconte Maggiolo

Art Storage 1980 156 Portolan chart by Vesconte Maggiolo

GEN MSS File 601+ Portolan chart of Western Europe and the Mediterranean Sea

GEN MSS 1486 Globe gores forgery after Martin Waldseemüller