By Emily Hyatt

On the final page of a small, unassuming book in the Beinecke’s “Italian Festivals” collection, there is something very curious. The book, titled La montagna circea (“Mountain of Circe”) and produced by the Italian academician Melchiore Zoppio, documents a celebration that took place in June 1600 in the city of Bologna. The text lavishly describes these festivities, recounting the performances of madrigals and arias, jousts and sieges, carried out by costumed characters dressed as figures from classical antiquity and contemporary Europe alike. All of this was standard fare in early modern festival books.

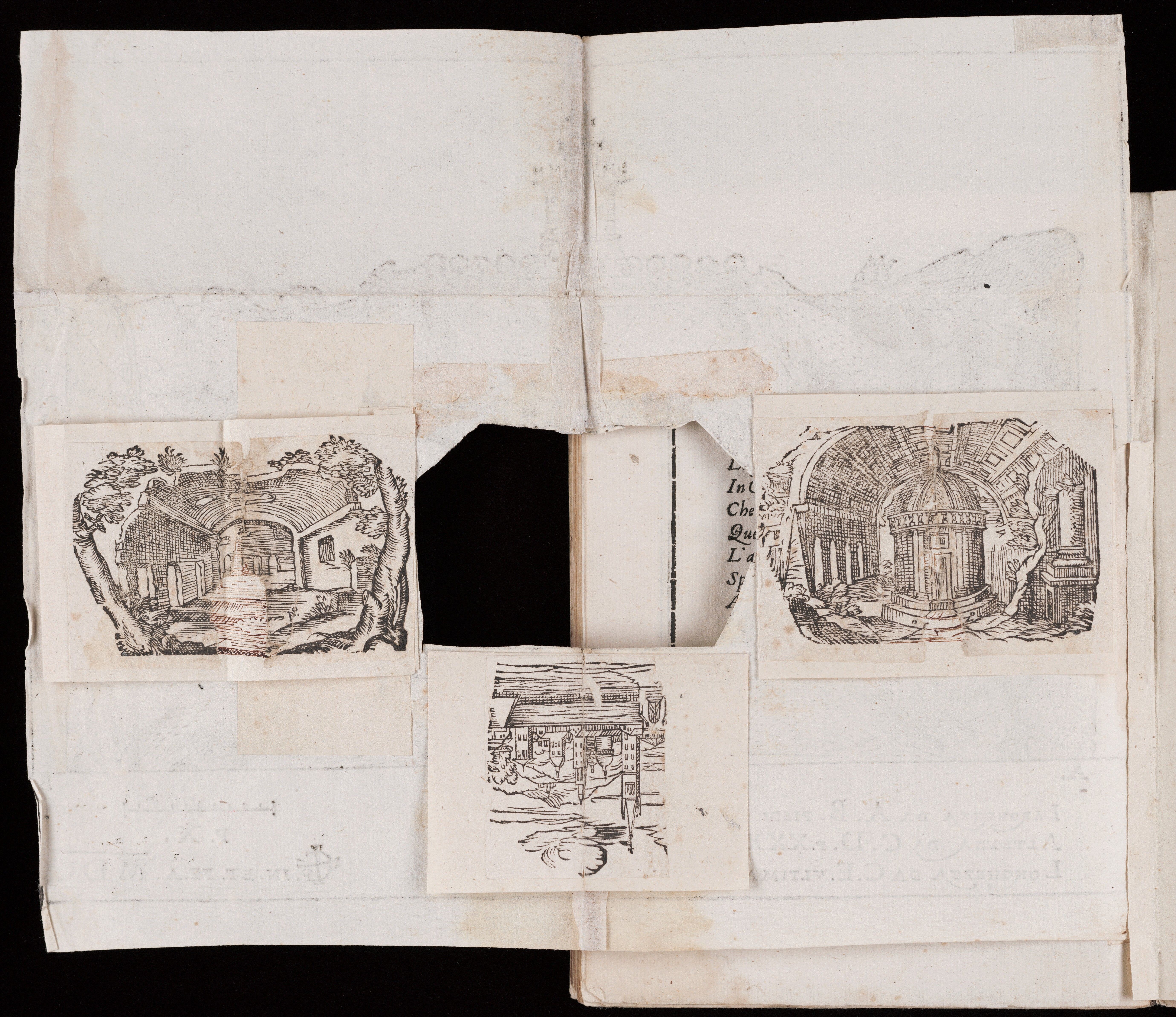

Far more unusual is the woodcut at the very end of the volume that, when unfolded, sprawls beyond the book’s edges. It seems to depict a massive rock formation, topped with a single domed tower. Wild herbs spring from cracks in this rocky mass, and a bright waterfall streams down its left side. Dense cross-hatching and irregular, curved marks lend a sense of both depth and craggy texture to the structure’s stones. As the name of the book suggests, this print depicts the mountainous home of Circe, the sorceress from ancient Greek mythology.

However, a closer look challenges the impression that the print simply represents a classical setting. Small staircases and dark, rounded doorways lie half-obscured in the mountain’s hatched shadows, suggesting the movement of people through and around its rock faces. Meanwhile, the flat plane in the foreground of the image appears less like a geological formation and more like a stage. A more immediate clue lies at the mountain’s center, where the middle of the print has been cut away completely. Turning the printed page over, the reader discovers three paper flaps affixed to the image’s reverse side, each illustrated with a different scene. When carefully unfolded by the user, these flaps can be placed over the center cut-out of the print, and in so doing, the “Mountain of Circe” is filled with different scenes: a grotto, a temple, and a faraway city with domes and bell towers.

This strange print, both moveable mountain and mechanical stage, takes on a new meaning when one engages with the text of La montagna circea itself. The text, written by Melchiore Zoppio, documents a festival that honored Margherita Aldobrandini, the Duchess of Parma, and her recent marriage to Ranuccio Farnese. The highlight of this festival was a play, which retold a story of two lovers, Picus and Canens, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In the version of the story created for La montagna circea, Circe takes Picus prisoner in the citadel atop her mountain. A diverse cast of characters come to Picus’s defense and seek to reunite him with his lover Canens, besieging the mountain of Circe and pleading for his release. In response to these actions, Zoppio writes that the Hyatt 2 machine’s “operator” (il mantenitore) initiated a physical transformation of the mountain: it spewed flames, emitted extraordinary noises, and broke apart, each time revealing a new scene in the mountain’s center.

The fold-out print at the back of the book allows the reader to recreate these scene changes, but with one crucial absence: the woodcut includes no human figures. Instead, it is the reader of the book who brings the mountain to life through touch and manipulation. The user’s movements not only recreate the transformations to the mountain of Circe during the festivities in 1600 but also reaffirm its exceptional stage design and mechanical achievement. In this way, the print encourages the user to cast themselves not as Picus, Canens, or Circe, but rather to imagine their hand as that of the operator upon whose technical expertise the festival’s central drama depended.

A student research post from the Fall 2024 graduate seminar The Mind of the Book (HSAR 620). More information and link to other research posts.