Exhibition Highlights an American Family’s Unique Link to German History

A new exhibition at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library explores an American family’s ancestral ties to the House of Hohenzollern – the German imperial dynasty that ruled from the dawn of the modern age to the end of the First World War.

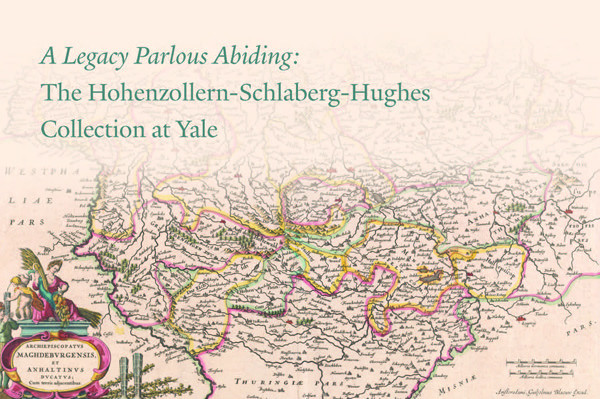

The exhibition, A Legacy Parlous Abiding: The Hohenzollern-Schlaberg-Hughes Collection at Yale, features artwork, maps, books, and correspondence tracing the fluctuating legacy of the House of Hohenzollern during the time of Frederick the Great, through the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and beyond.

The collection was gifted to Yale University in 2011 by Thomas Lowe Hughes, who carefully assembled it from a trove of memorabilia he found hidden away in his grandfather’s attic in Minnesota in 1938.

“Imagine being a 12-year-old boy and discovering that you were the descendant of a centuries-long line of princes, kings and emperors. That was Thomas Hughes’s experience,” says Kevin Repp, the Beinecke’s curator of Modern European Books and Manuscripts. “Through his generosity and care, we are able to share this remarkable collection charting the tempestuous legacy of a major European dynasty.”

The items on display were in large part assembled in America, after Hughes’s ancestor Charles Frederick Schlaberg II, fleeing the turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars, left Germany first for Scotland and then for Canada in the mid-19th century. Four years before his death, Schlaberg settled in Minneapolis, bringing his collection of memorabilia along with him.

Discovered a few decades later by Schlaburg’s grandson Dr. Thomas Lowe, the collection grew as the distant American relations exchanged cards and gifts with the rulers of the newly united German Empire from the 1880s on.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Dr. Lowe hid the collection in his attic out of concern that his German heritage would harm his career in local politics. His grandson, Thomas Hughes, would rediscover it in the attic more than two decades later.

Over more than 70 years, Hughes, a distinguished diplomat who served as an Assistant Secretary of State during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, carefully developed the collection before donating it to Yale. The collection is housed at the Beinecke Library, the Yale University Art Gallery, and the Yale Center for British Art. Materials from each institution are on display.

The exhibition features a variety of maps – a particular strength of the collection. Two maps on display were drawn by Gerhard Mercator, the preeminent mapmaker of his day and the inventor of the “Mercator Projection” technique for translating three-dimensions into two.

Other items on display include a letter from Frederick the Great to one of his commanders during the Seven Years’ War. Intricate and elaborate family trees on exhibit trace the Hohenzollern line across a landscape of duchies, counties, episcopal states, and kingdoms.

Two portraits displayed at the library’s entrance are among the collection’s most valuable items: Franz von Lenbach’s oil portrait of the Hohenzollern Emperor Frederick IV, and Thomas Philipps’s oil portrait Charles Frederick Schlaberg II. The paintings are on loan from the Yale University Art Gallery and the Yale Center for British Art, respectively.

Though the First World War is sparsely represented in the collection, the exhibition includes correspondence from the 1920s between Dr. Lowe and Wilhelm II when the deposed Kaiser was living in exile in Holland. A typewritten letter from 1929 expresses the Kaiser’s special thanks for Dr. Lowe’s gift of a two-volume biography of Abraham Lincoln.

The exhibition also includes correspondence documenting Hughes’s attempts to track down his Hohenzollern relations as Nazi terror spread across Europe. While most had kept their distance from Hitler and Nazi ideology, the exhibition includes correspondence from August Wilhelm von Hohenzollern, who eagerly supported the Third Reich. He would die in prison after the war.

The collection contains hundreds of letters, postcards, and photos documenting the family’s experiences with reconstruction and the gradual transition to a democratic society after the Second World War. On view are letters to Hughes from Hohenzollern relatives who spent the war years in exile and others who survived the catastrophic bombing of Dresden.