See the manuscript online: Robert Reed, The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict, or the Inmate of a Gloomy Prison

Years ago, a rare-books dealer browsing at an estate sale in Rochester came across an unusual manuscript, dated 1858. The family selling it said little about where it had been for the last 150 years. It appeared never to have left upstate New York.

Scholars now believe that the mystery manuscript is the first recovered memoir written in prison by an African-American, a discovery that Yale University says it made after authenticating the document and acquiring for its Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

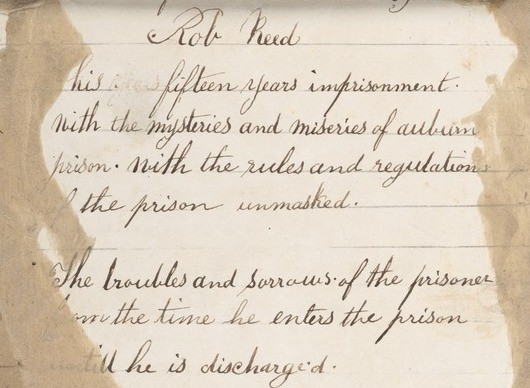

The 304-page memoir, titled “The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict, or the Inmate of a Gloomy Prison,” describes the experiences of the author, Austin Reed, from the 1830s to the 1850s in a prison in upstate New York.

Caleb Smith, a professor of English at Yale who has written extensively about imprisonment, said he believed the manuscript to be authentic. Reed’s account was corroborated through newspaper articles, court records and prison files, with help from Christine McKay, an archivist and researcher who also works for the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Manhattan.

“It’s still a very unusual thing for us to find any previously unknown document from this period by an African-American writer,” Mr. Smith said. “From a literary point of view, I think there’s no other voice in American literature like the voice of this penitentiary narrative, which has a very lyrical quality. And from a historical perspective, what makes this so fascinating at this moment is the deep connection between the history of slavery and the history of incarceration.”

Nancy Kuhl, a curator at the Beinecke library, said the manuscript “significantly enriches the canon of 19th-century African-American literature and deepens our understanding of all 19th-century America.”

Reed is believed to have been born a free man near Rochester. As a young man, according to Yale’s research, he was sent to the New York House of Refuge, a juvenile reform school in Manhattan, where he learned to read and write. By the 1830s, a string of thefts resulted in his incarceration in a state prison in Auburn, now known as the Auburn Correctional Facility, which was built in 1816.

The manuscript, written with the dramatic flair of a natural storyteller but in unpolished English, with grammatical and spelling errors, traces his life from childhood to his years at Auburn. It is written under the name Rob Reed, although it is unclear why he used that name, according to Yale.

In the early pages, Reed describes a childhood incident when, encouraged by his sister, he disguised himself as a girl and attempted to kill a man to avenge an earlier whipping.

“I cocked the pistol and with an uplifted hand of revenge I let fire and missd my shot,” he wrote. “It was a dark night. I could hardly see my hands before my face. The old man hollowd murder, murder, but before any aid could get to him I drew the knife a cross his shoulders wich left a deep wound for months afterward.”

Later, Reed describes torturous punishments at Auburn that were typical at the time, including frequent whippings and a device known as the shower-bath, a kind of precursor to waterboarding that was occasionally fatal.

“Stripping off my shirt the tyrantical curse bounded my hands fast in front of me and orderd me to stand around,” Reed wrote. “Turning my back towards him he threw Sixty seven lashes on me according to the orders of Esq. Cook. I was then to stand over the dreain while one of the inmates wash my back in a pail of salt brine.”

Eileen McHugh, the executive director of the Cayuga Museum of History and Art, near Auburn, said that Reed would have been writing under arduous conditions. At the time, prison cells were unlit and had no windows. Men at Auburn were forced to work 10 hours a day in total silence. (In 1890, Auburn would become the site of the first execution by electric chair.)

“I don’t know that it would be forbidden,” Ms. McHugh said of a prisoner’s ability to write, “but nothing would have made it easy.”

Reed probably had extremely limited access to reading material — perhaps little more than the Bible — but the manuscript makes mention of “Robinson Crusoe,” the 1719 novel by Daniel Defoe, and a 1788 poem by William Cowper, “The Morning Dream.”

Prisoners were not allowed to speak and were required to move in lock step, so that they were never face to face with one another. They had no leisure time.

“This was, in the beginning, considered progressive, because they thought it was a way of rehabilitating these criminals,” Ms. McHugh said. “In reality, it was completely contrary to human nature.”

There is reason to believe that Reed hoped that the book would eventually find an audience. Its subtitle is “With the Mysteries and Miseries of the New York House of Reffuge and Auburn Prison Unmasked.”

He frequently addresses the reader directly and appears to have shared the manuscript with someone, though that person’s name is illegible in a note inside it.

Mr. Smith, the Yale professor, said he is preparing the manuscript for publication. “We know that this was never printed, but certainly Reed wanted it to be,” he said. “He’s not writing for intimates, he’s not writing for himself. He’s writing it for the public.”