Yonekazu Satoda was confined at an assembly center in Fresno awaiting transfer to the Jerome Relocation Center, a swampy and barren internment camp in Arkansas, when he noted a missed milestone in his diary.

“Today was supposed to be my graduation at Cal,” he begins an entry dated May 15, 1942. It was the second entry of a diary that covers his nearly three-year internment.

Satoda, a California-born American citizen, goes on to briefly describe his day. It was “very hot.” He ate two meals, one at noon and another at night. He took a walk and had “a long bull session” with friends.

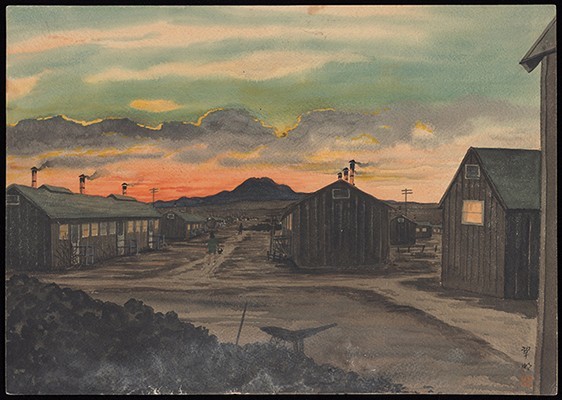

“Out of the Desert”

His diary is among about 100 items featured in “Out of the Desert: Resilience and Memory in Japanese American Internment,” a new exhibit at Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library that highlights the university’s extensive collections related to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Drawing on materials housed at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library and Sterling Library’s Manuscripts and Archives, the exhibit shows how everyday creative production and learning — writing, painting, reading, music, etc. — helped the internees cope with the camps’ stressful and harsh conditions and develop alternative narratives to their confinement. It features letters, artwork, and literature, as well as photographs of camp scenes by Ansel Adams. An online component offers viewers access to Satoda’s entire diary as well as historical background and dozens of items not featured in the exhibit space.

Posted prominently in public, posters like this one instructed “all person’s of Japanese ancestry” to report for “evacuation” by April 3, 1942. Many internees lost their property as they rushed to store and sell their belongings to pack only what they could carry.

Posted prominently in public, posters like this one instructed “all person’s of Japanese ancestry” to report for “evacuation” by April 3, 1942. Many internees lost their property as they rushed to store and sell their belongings to pack only what they could carry.

Courtney Sato, a third-year doctoral student in American studies and the exhibit’s curator, says Satoda’s line about missing his graduation underscores the injustice that he and approximately 100,000 other Japanese Americans endured.

“It’s a powerful entry that elicits such a visceral reaction, to be denied something as important as a college graduation,” she says. “It shows the reality that he was grappling with in a way that I hope will resonate with students here at Yale.”

Satoda’s diary is displayed beside the cardboard tube in which the University of California-Berkeley, mailed him his diploma. Adding insult to injury, the university sent the diploma to Satoda’s Berkeley address, and he was charged four cents in postage to have the diploma redirected to the assembly center.

When the Beinecke acquired Satoda’s papers on the private market in 2013, it was unknown whether he was still alive. Initial attempts to contact his family were unsuccessful. In the course of preparing the exhibit, Sato managed to reach Satoda, who is 94 years old and resides in San Francisco. If his health allows, he will travel to New Haven to attend the exhibit’s opening reception on the afternoon of Thursday, Nov. 5

Behind the barbed wire

President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942 authorizing the secretary of war to designate certain regions as military zones where “any or all persons may be excluded.” The order provided the legal basis for the forced removal of people of Japanese ancestry living on the Pacific Coast first to temporary assembly centers and then to one of 10 internment camps in the country’s interior.

The exhibit opens with a broadside that was used to inform “All Persons of Japanese Ancestry” that they would be “evacuated” from their homes in one week. It instructed “evacuees” to bring linens, plates and cutlery, spare clothes, and toiletries. It informed them that the government would provide services for storing, leasing, or selling their cars, real estate, livestock, household goods, etc.

The first sections of the exhibition include materials concerning the administration and organization of the camps and examples of how the camps were depicted in the media. Journalists used euphemisms like “relocation center” and “evacuation” that disguised the nature of life in the internment camps, which were surrounded with fences, barbed wire, and watchtowers. A June 8, 1943 photo essay in the Los Angeles Times is headlined: “Life at Poston, One of the Largest Jap Relocation Centers.”

The internment policy drew protests from people who recognized the injustice of it. A pamphlet on display published by The American Baptist Home Mission Society argues “democracy demands fair play for America’s Japanese.”

Numerous religious and humanitarian groups opposed the internment. This pamphlet was published by the American Baptist Home Mission Society.

Satoda’s diary anchors a section on daily camp life. He writes continually of his boredom and frustration. The diary also chronicles his resilience. He overcomes the grinding monotony by playing bridge, baseball, and basketball. He attends dances and goes on dates. He takes classes and “chews the rag” with friends.

A section on education and libraries features materials from the Poston internment camp in Arizona that were donated to Yale by Nathan Van Patten, Stanford University librarian and honorary Yale War Collection adviser.

Van Patten collected hundreds of items for Yale during the war. Those materials include a sign for Poston’s library, a poster about a summer reading contest, a class scrapbook project on the causes of war, and a yearbook from the camp’s high school.

“Van Patten collected very broadly because he was trying to build the largest collection of Japanese American material on the East Coast,” Sato says. “He collected items that might not have seemed valuable at the time, like a poster from the camp library, but that sort of ephemera really speaks the daily lives of the internees.”

The exhibit includes sections on internee artwork and connections forged between the internees and activists on the outside who opposed the internment policy. There is a letter from internee Edith Shigeishi to Elizabeth Page Harris, a Quaker and a pacifist who led efforts to assist Japanese Americans during the war, praising the generosity of “outsiders” to provide presents for the internees during Christmas.

“I wish you could have seen the children’s faces when the Santa said that he had a present for every child,” she wrote. “They were so happy that they jumped up and down and screamed.”

The exhibit’s closing sections focus on the resettlement and repatriation of internees after the mass exclusion orders were revoked on Dec. 17, 1944 and the subsequent debate over redress, reparations, and the legacy of the internment camps.

Locating Mr. Satoda

George Miles, the William Robertson Coe Curator of the Yale Collection of Western Americana at the Beinecke, seized the opportunity in 2013 to acquire Satoda’s diary and other materials, including his photographs and home movies from the camp.

A handmade Christmas card from the Poston internment camp in Arizona.

“To acquire an unpublished firsthand account by a young internee is really special,” says Miles.

At the time of the acquisition, Miles attempted to locate Satoda’s family. An oral history of internment life by Satoda’s wife, Taka “Daisy” Satoda, had been published, and she had a Facebook page concerning that project. Miles contacted her through the Facebook page, but she did not respond.

Sato made another attempt to reach the Satodas while organizing the exhibit. A contact at the Smithsonian Institution confirmed that Satoda was alive and provided her an address. She wrote Satoda a letter explaining the situation, and he replied.

Sato says that Satoda told her that he had forgotten about the diary, but the line about his missed graduation jogged his memory.

“As soon as I quoted that line, he said, ‘Yes, that’s my diary,’” she says.

Satoda left the internment camp after the U.S. Army drafted him in 1945. After completing basic training at Fort Hood in Texas, he served at a military intelligence language school at Fort Snelling Minnesota. After the war, he spent nearly two years as an intelligence officer in Japan. He served in the U.S. Army Reserves from 1949 to 1969, retiring as a major.

The Satodas had three children. He made a living as an accountant in San Francisco.

It still is not clear how his papers landed in the rare book market.

Satoda contributed the cardboard tube that had held his diploma to the exhibit.

Sato says she is looking forward to meeting Satoda in person when he and his family come to Yale for the exhibit’s opening reception..

“Mr. Satoda has made this project all the more rewarding and worthwhile,” she says.

“Out of the Desert” is on view in the Memorabilia Room in Sterling Memorial Library through Feb. 26, 2016. The opening reception begins at 4 p.m. on Thursday, Nov. 5 in Sterling Library’s lecture hall. It will feature remarks by Professor Gary Okihiro, the founding director of the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race at Columbia University. A digital component of the exhibit will go live on Nov. 5 at outofthedesert.yale.edu.