Bizarre, nos. 1-2; new series, nos. 1-46 (Paris, 1953-1968)

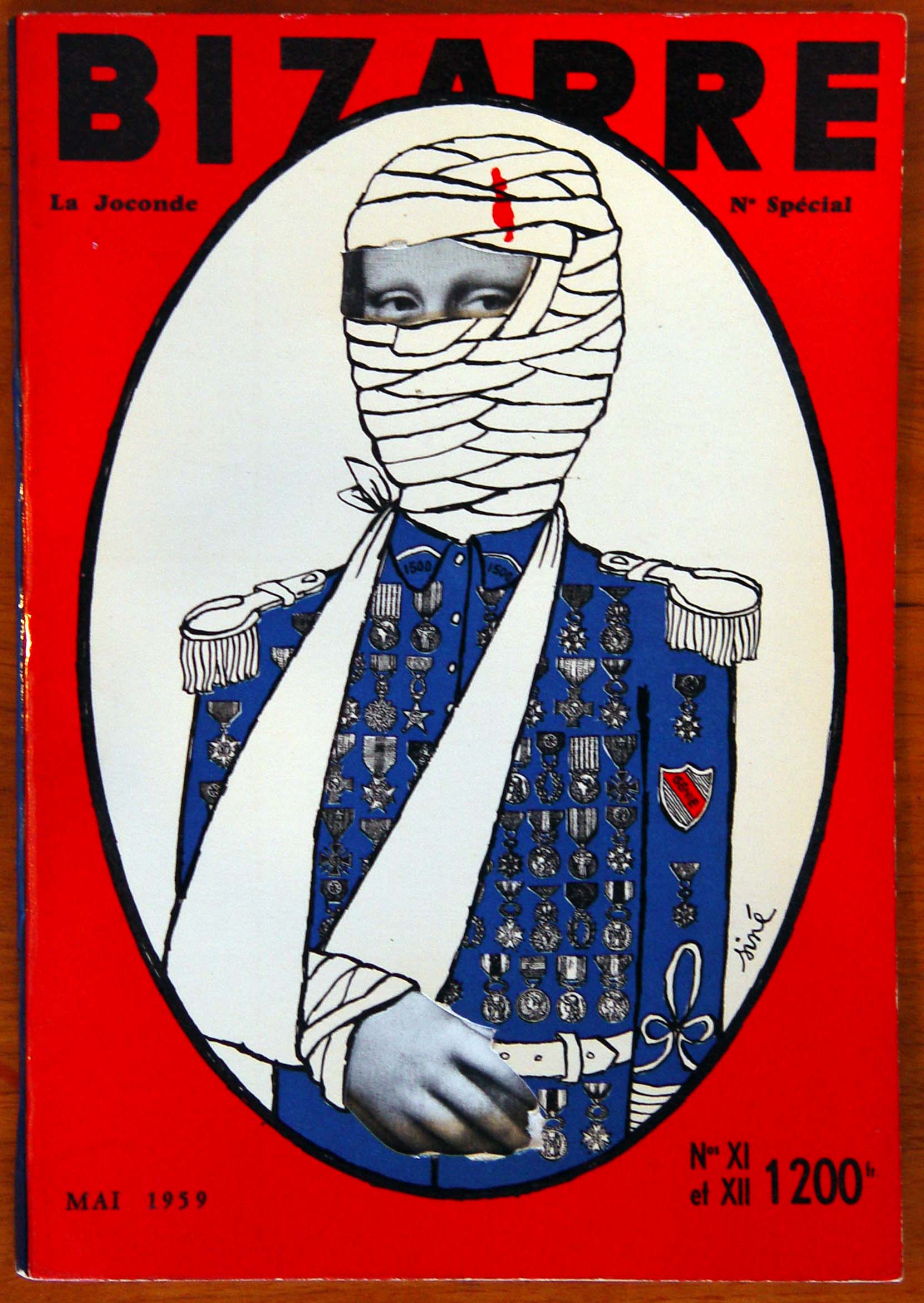

Siné’s Cover for Bizarre, no. 11/12 (May 1959), a special issue devoted entirely to “Jocondoclastie,” or the playful misappropriation (and willful defacement) of the Mona Lisa

Founded by Eric Losfeld–who went on to publish Jean-Claude’s notorious Barbarella comics in the early 1960s–Bizarre lasted for just two issues before falling off the map in 1953. The magazine was soon revived, however, by Jean-Jacques Pauvert and Michel Laclos, who kept its torrent of iconoclastic wit, cultural criticism, and artistic daredevilry running uproariously from 1955 right up to the eve of the Paris uprisings in the spring of 1968. No stranger to controversy, Pauvert made a name for himself in the immediate postwar years publishing (at times clandestine) editions of Sade. His new bookshop on the Rue Bonaparte was quickly put under police surveillance when it opened in 1956, just a year after he restarted Bizarre, and the besieged bookseller/ publisher found himself at the center of the “Affaire Sade,” as the French government stepped in to ban the publication and sale of such works. Clashes with authority and public controversy also hounded other contributors to the journal, including its ‘s star illustrator, Siné. An anarchist with sharply anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist, and (as many would later find) anti-semitic views, Siné felt pressured to quit his position as political cartoonist for L’Express due to his virulent opposition to the Algerian War, which provoked public outcry from many readers, and for a time in the early sixties he worked on Révolution africaine, a journal financed by the Algerian resistance organization FLN. When the uprisings came in 1968, Siné again joined with Pauvert to found the magazine L’Enragé, an important document of the rebellious spirit of the late sixties and early seventies recently acquired by Beinecke as part of the Philippe Zoummeroff Collection of May 1968 Paris Counterculture.

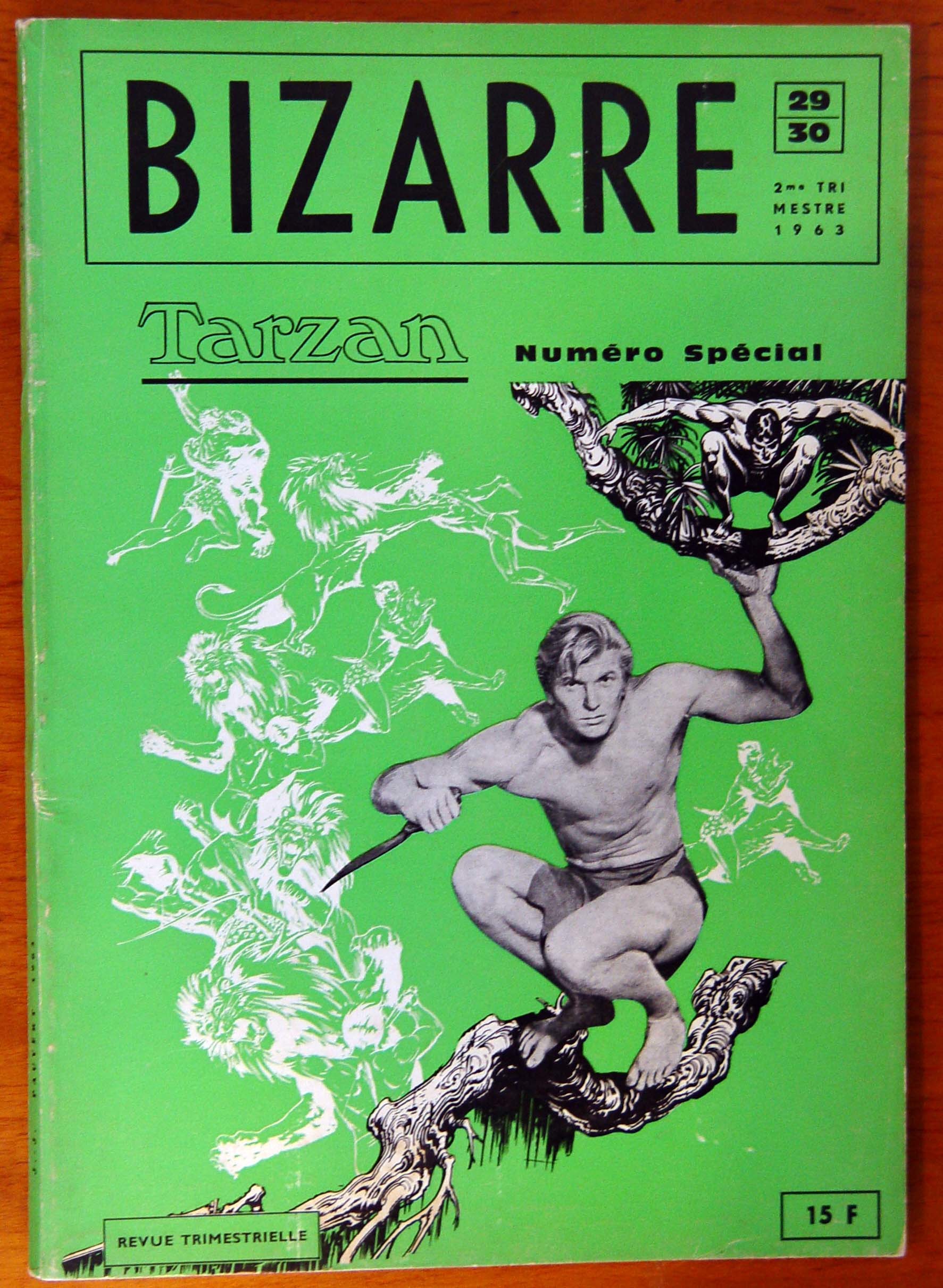

Special Tarzan Issue, Bizarre, no. 11/12 (1962)

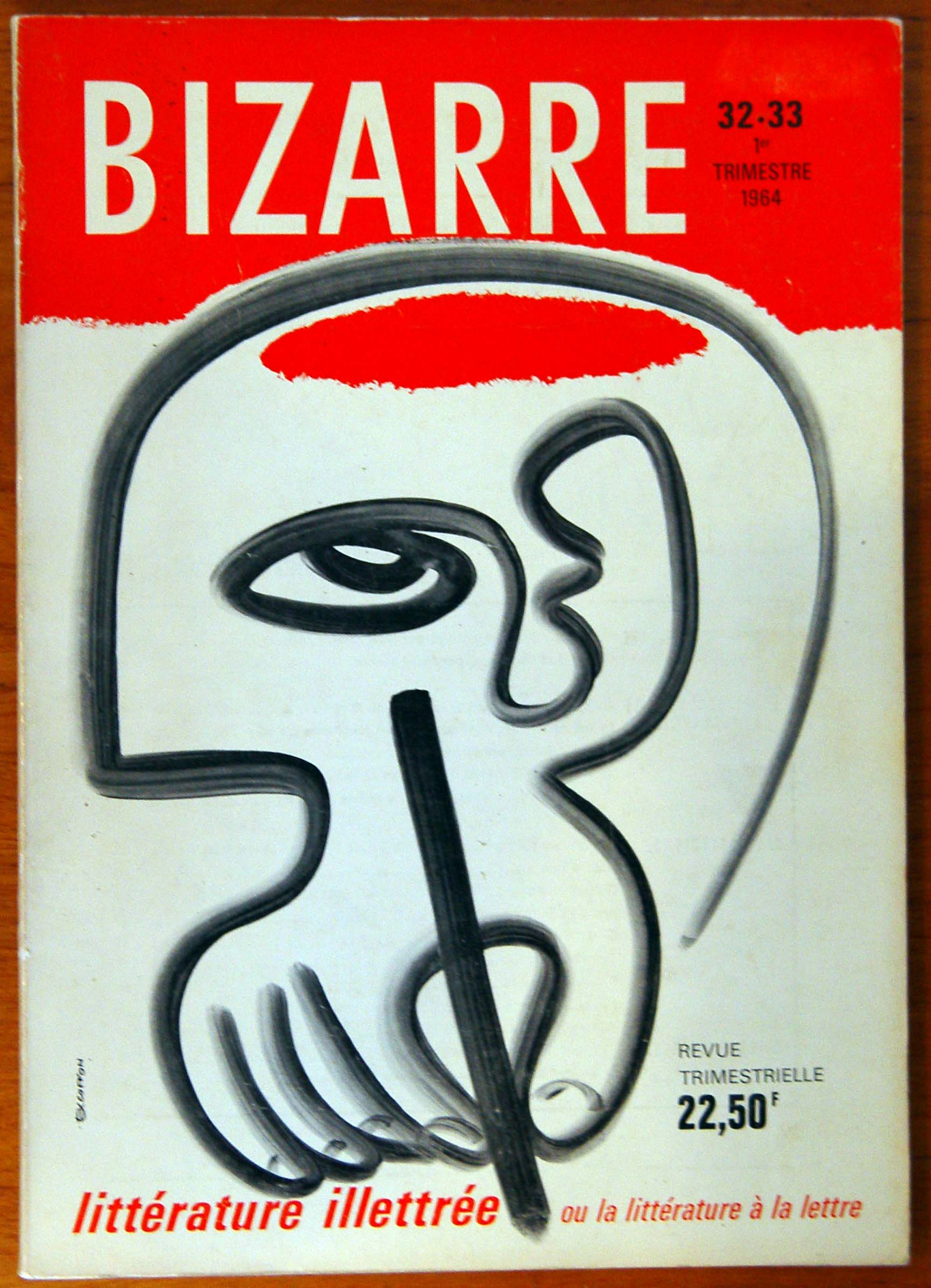

Special Issue on Lettrism, Bizarre no. 32/33 (1964)

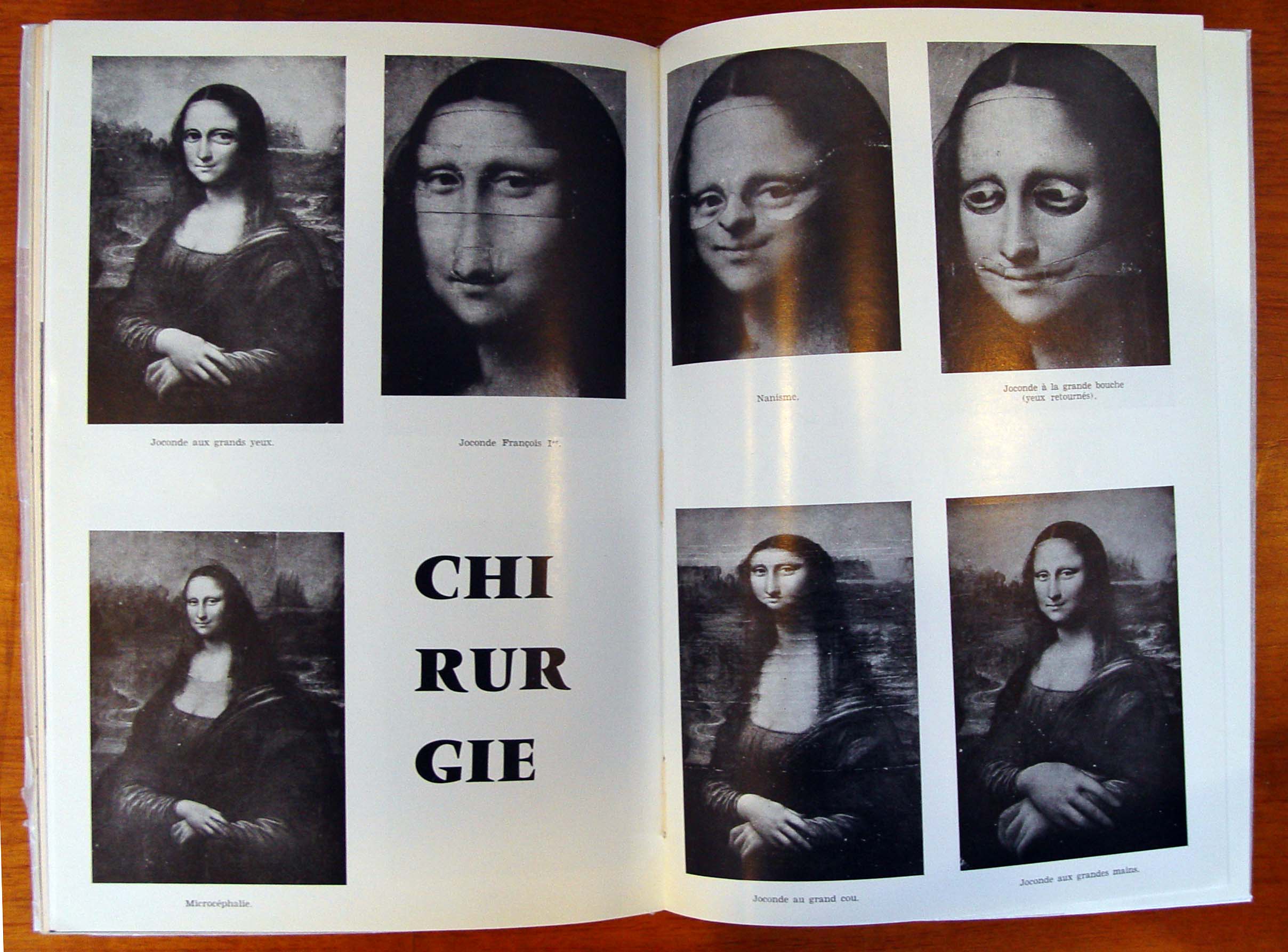

Channeling undercurrents of political unrest and cultural discontent, as well as a simple delight in mockery, Bizarre became an important artistic expression of the culture of protest that peaked (at least initially) in the revolts of May ‘68. Bizarre excelled in the scavenging techniques of détournement and bouleversement wielded by avant-garde poets, artistists, and cultural critics in the Paris of Situationism and Lettrism (one issue of the magazine is entirely devoted to a critical engagement with the latter). Siné’s cut-out design for the cover of Bizarre no. 11/12 (shown at top) cloaks the Mona Lisa (La Joconde) in the garb of a heavily decorated (and heavily wounded) military officer, but inside the covers one finds a medley of playful misappropriation, commercial exploitation, disfigurement, and material destruction. There are paint-by-number Mona Lisas, Mona Lisa gag postcards, crossword puzzles, postage stamps, posters, Mona Lisa comic strips and measurements of her physique, “typographical” portraits of the Mona Lisa, and countless other permutations, all gathered around Jean Margat’s tongue-in-cheek theoretical treatise, “Introduction à la Jocondoclastie” (Introduction to Mona-Lisa Iconoclasm). The last dozen or so pages are devoted to “exercises” in this new art–“découpages,” “clivages,” “déformations,” “trucages photographiques,” “chirugie,” and “destructions matérielles.”

(Cosmetic?) Surgery on the Mona Lisa, Bizarre, no. 11/12 (May 1959)

Miss Mona Lisa 1957,” shown with labels for Mona Lisa brand cheese and cigars and a pin featuring the Eiffel Tower, Bizarre, no 11/12 (May 1959)

<img title=”bizarre-006-edit3” data-cke-saved-src=”/sites/default/files/archive_files/2009/05/bizarre-006-edit3.jpg?w=300” src=”/sites/default/files/archive_files/2009/05/bizarre-006-edit3.jpg?w=300” alt=” ” les=”” limitaions=”” de=”” mad=”” a=”” l’egard=”” la=”” segregation=”” sont=”” celles=”” du=”” liberalisme=”” american=”” dans=”” son=”” ensemble=”” …=”” cette=”” hypocrisie=”” bonne=”” foi=”” qui=”” pousse=”” plus=”” honnetes=”” considerer=”” que=”” mystique=”” anti-negre=”” ne=”” constitue=”” meme=”” pas=”” matiere=”” scandale,=”” l’accepter=”” passivement=”” sans=”” se=”” sentir=”” troubles=”” par=”” leur=”” propre=”” silence,=”” est=”” un=”” des=”” elements=”” inquietants=”” l’ideologie=”” americaine.”=”” bizarre=”” no=”” 6=”” (november=”” 1956)”=”” width=”300” height=”225” >mad=”” about=”” mad:=”” “les=”” mad à=”” l’égard=”” ségrégation=”” libéralisme=”” honnêtes à=”” anti-nègre=”” même=”” matière à=”” scandale, à=”” troublés=”” éléments=”” inquiétants=”” l’idéologie=”” américaine.”=”” 1956)

Cinema and pop culture were also popular themes. Tarzan, Boris Karloff, Bela Lagosi, Brigitte Bardot share layouts with “monsters” from circus sideshows, film noire, comic strips, and lots of American beauties pointing guns at the viewer. A jarring flux and flow strongly reminiscent of the illustrations of Internationale Situationniste that were being published in the same years. The editors of Bizarre had a penchant for revealing the dark side of American popular culture, as in this stinging critique of MAD magazine, chastized for its lily-white heros and its complete silence on the topic of racism and the civil rights movement in the United States. The rising wave of détourned political comics, which spread quickly throughout Europe in the early sixties and became a staple visual component of protest literature in the wake of 1968, certainly ripples through the 48 issues of Bizarre from first to last.