Cell Song

Night Music Slanted

Light strike the cave

of sleep. I alone

tread the red circle

and twist the space

with speech.

Come now, etheridge, don’t

be a savior; take

your words and scrape

the sky, shake rain

on the desert, sprinkle

salt on the tail

of a girl,

can there anything

good come out of

prison

by Etheridge Knight

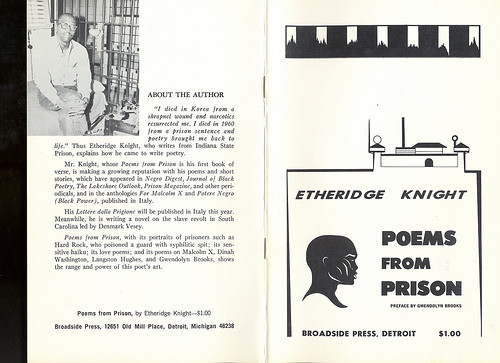

The prison literature genre dates back at least 524 AD, when Boethius wrote his Consolation of Philosophy while imprisoned and awaiting execution by Theodoric the Great. Incarceration in modern America has provided its share of inspiration for writers and poets, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Etheridge Knight, and Stewart Brisby, among many others. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” is one of the most famous examples of prison literature, and its argument for action as the only possibly efficacious form of rhetoric is of a piece with poems as disparate as Knight’s “Hard Rock Returns to Prison from the Hospital for the Criminal Insane,” wherein the narrator laments Hard Rock’s lobotomy because, “He had been our Destroyer, the doer of things / We dreamed of doing but could not bring ourselves to do,” and Harold E. Packwood’s “The Red-Neck Coke Machine,” which returns the poet’s quarter “Along with a note, / Saying, / “Sorry, you’ll have to use / The back of the machine.”

Packwood’s poem is one of his nine poems that appear with those of twenty other prisoners in the chapbook, Betcha Ain’t: Poems from Attica. This anthology, edited by Celes Tisdale, who visited the prison to teach poetry workshops beginning in 1972, was published in 1974, three years after the Attica Prison Riot that attracted international attention to treatment of prisoners in the United States, and the excesses of officially sanctioned violence. The collection also includes selections from Tisdale’s journals, and biographies of the contributors. Some of the biographies appear to be written by the individuals themselves, while others are by Tisdale. One of the latter, of Mshaka (Willie Monroe), reflects perhaps as well as anything in the collection the uncertainty of life in maximum security. It reads, “Diminutive, incisive young man who was released from prison or transferred after two sessions in the workshop.”

Other volumes of prison literature in the Beinecke Library include Willie J. Williams’ A Flower Blooming in Concrete (1976), Prisoner B. 8266’s (of an unidentified penitentiary) A Tale of a Walled Town and Other Verses (1921), Reachin’ Out by “Christians serving time in the Arizona State Prison,” and Ralph C. Hamm, III’s Dear Stranger/The Wayfarer. The collection also includes a small collection of manuscripts, photographs, and correspondence related to Hamm’s writings and describing his literary work and life inside Massachusetts Correctional Institution-Cedar Junction, in South Walpole, Massachusetts.

Collection description prepared by Jon Sudholt, Y’08.