By Madeleine Trépanier

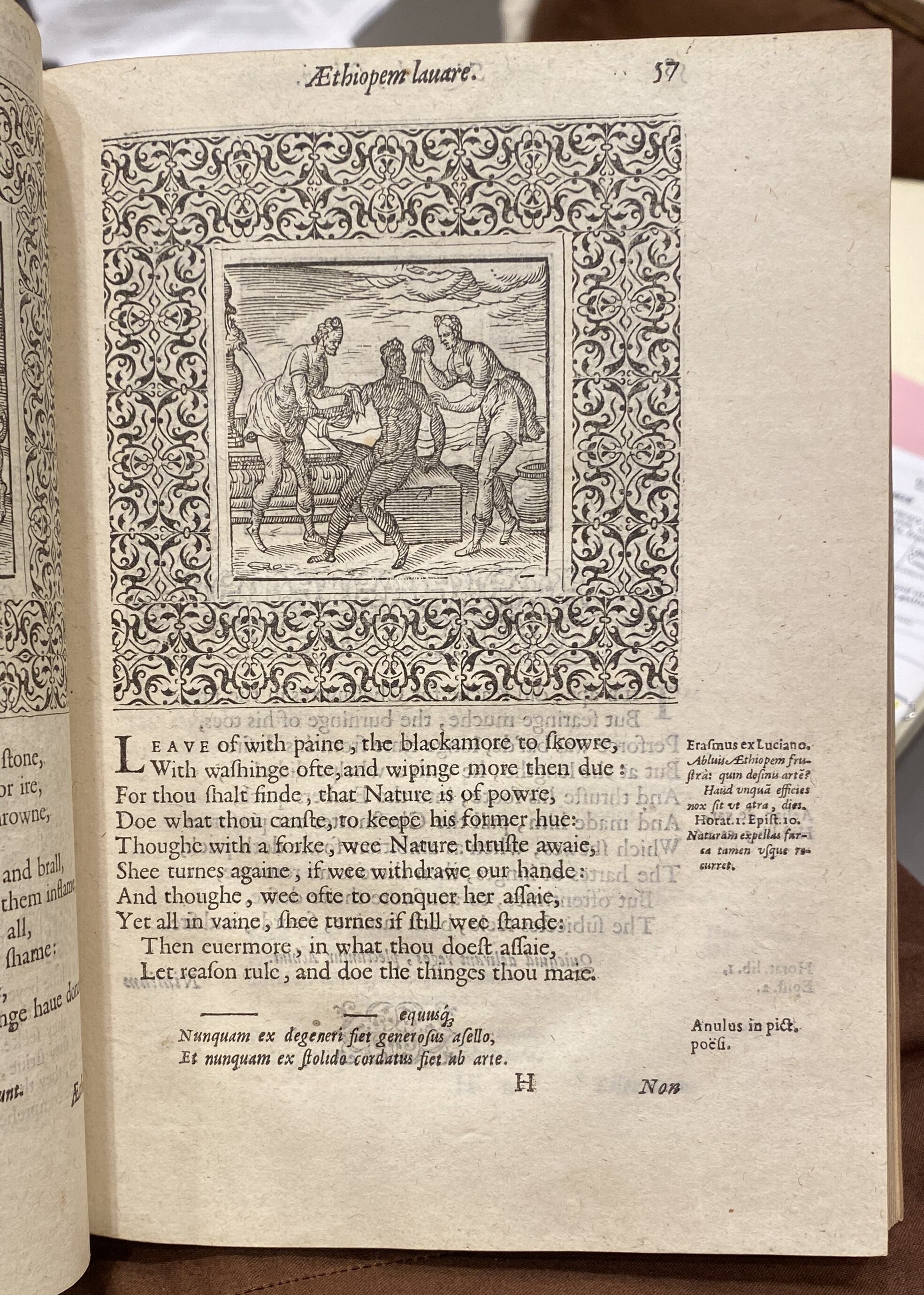

At the heart Geoffrey Whitney’s A choice of emblems lies a troubling woodcut. Two White figures outnumber a central Black figure, brandishing rags. A short poem below tells us they seek to ‘scowre’ him, evoking the pain their scrubbing inflicts on his body. To change the ‘hue’ of his skin is impossible, but the attempt is still torturous. The central figure’s agonized gaze is averted from the viewer’s, while his nudity—in contrast to his two dressed captors— deliberately lays his body open to scrutiny. Racial difference is depicted starkly, in black ink pressed into white paper. We are looking at an image of racism made for the medium of print, rendered schematic and reproducible.

When Whitney selected this emblem for his book in 1586, however, he hoped it would appeal to his readers rather than horrify them. Observe the elegant symmetry of the White figures, their limbs posed with choreographed grace. Behind them trickles a fountain, providing the water with which they seek to cleanse their victim. Yet fountains are most often to be found in pleasure gardens and or the pages of literary romances. An ornamental border frames the image as an aesthetic object, just like any other woodcut in the book. The image is presented as a place to rest the gaze, a place to reflect.

Emblems were designed to prompt exactly this kind of leisurely contemplation. Pioneered by the Italian humanist Andrea Alciato, the emblem genre offered a unique blend of witty verbiage and symbolic image. Three puzzle pieces—the motto above, the picture at the center, and the short verse below—slotted together to deliver a moral lesson. This genre grew out of the popularity of short classical poems, but Alciato’s chosen word for his creation, emblemata, references the decorative inlay used by artisans, like an inset mosaic or metalwork. The emblem’s form is designed to feel both scholarly and playful: something with the moral authority of antiquity and the visual allure of a newly minted art object.

Emblematists were not always authors or artists in our modern sense. In other words, they did not always aim to produce original creative work. Instead, they often drew on existing emblem books, adapting their contents to suit their own ends. Whitney was no exception. His emblem Aethiopem lavare (“To wash the Ethiopian”) is a recognisable copy of one of Alciato’s own emblems, titled Impossibile (“The impossible”). The central image comes directly from a series of woodcuts re-cut for a 1577 edition of Alciato. The motto, too, would have been familiar to an early modern reader. This phrase “to wash the Ethiopian” had both Biblical and classical antecedents; it was used as a commonplace to describe the act of trying—and failing—to produce spiritual reform in another person. The proverbial “Ethiopian” can neither shed his dark ‘hue’ nor his heathen status. An elaborate system of humanist citations around the edge of the page signals the adage’s classical pedigree. The poem below, however, is Whitney’s own handiwork. “Leave off,” he tells his reader in a confident imperative, trying to change what you cannot change. “Let reason rule, and doe the thinges thou maie.” Blackness is shrunk down to mere illustration of an abstract moral.

Whitney was not the first English emblematist, but he did print the first hugely popular collection of emblems for an English-speaking readership. It was Whitney who made the emblem a part of everyday life for people in England, from schoolboys to Shakespeare. He did so through extensive contact with the Netherlandish artisans of his day, and in the mid-1580s travelled to Leiden, the hub of Dutch emblem printing. It was in the Netherlands that A choice of emblems was published: a strategic import with a large target audience.

A student research post from the Fall 2024 graduate seminar The Mind of the Book (HSAR 620). More information and link to other research posts.