The week before Beinecke staff began to work from home, the library acquired three parchment fragments of Sefer Torah scrolls, traditional manuscript copies of the Old Testament, or Torah, written in Hebrew on parchment scrolls. The Torah is the central Jewish text, and along with the Talmud (the oral law and rabbinical teachings), the Torah forms the basis for belief and ritual practice. Torah scrolls are sacred objects and are kept by Jewish communities and housed in synagogues in special cabinets called arks. They are used in prayer services and read from regularly throughout the year on the Sabbath and holidays, progressing through the five books of Moses during the course of each year. For centuries torahs have been produced in nearly the same manner according to strict rituals and scribal traditions. A Torah must meet certain standards to be considered “kosher” or usable for ritual prayer. A Torah is hand-written by a sofer, a ritual scribe, who is trained in specific styles of Hebrew calligraphy that include text size, style, and layout. A Torah is made up of specially prepared parchment sheets, from the skins of a kosher animal. The sofer writes the Torah by hand using specially prepared ink and a turkey feather quill. The finished written sheets are then sewn together with dried tendons (also from a kosher animal) to make a long scroll and each end is sewn to a wooden roller. Since they are used multiple times a week, torahs take a lot of wear and tear, both from handling and environmental factors, and have to be repaired from time to time. Sofers are often able to repair a Torah by rewriting the text but sometimes a full parchment sheet must be replaced.

The three fragments in this new acquisition likely represent two different Torah scrolls, and may have resulted from repairs. They also may have come from Torah scrolls that were purposefully dismantled and destroyed during periods of antisemitic violence and persecution. Since Torah scrolls are rarely signed or dated, it can be difficult to determine the provenance of full scrolls, let alone fragments. We consulted with Rabbi Levi Selwyn from Sofer on Site, a group of trained scribes based in Florida who provide scribal services to synagogues and Jewish communities worldwide. Rabbi Selwyn examined photographs of the fragments and identified the calligraphic style as “a kabbalistic writing, sort of a mix between Sefardi and Ashkenazi.” He explained that “The sharp tall ‘V’ shaped legs of many of the letters say it was probably written in Germany.” Over the centuries, different traditions evolved in ritual practice for the Jewish communities of Ashkenaz (Eastern Europe) and Sefarad (the area around the Mediterranean Sea, including Portugal, Spain, the Middle East and Northern Africa). This included the scribal traditions of writing and ornamenting Torah scrolls which enables a trained scribe to identify the approximate provenance of a Torah fragment.

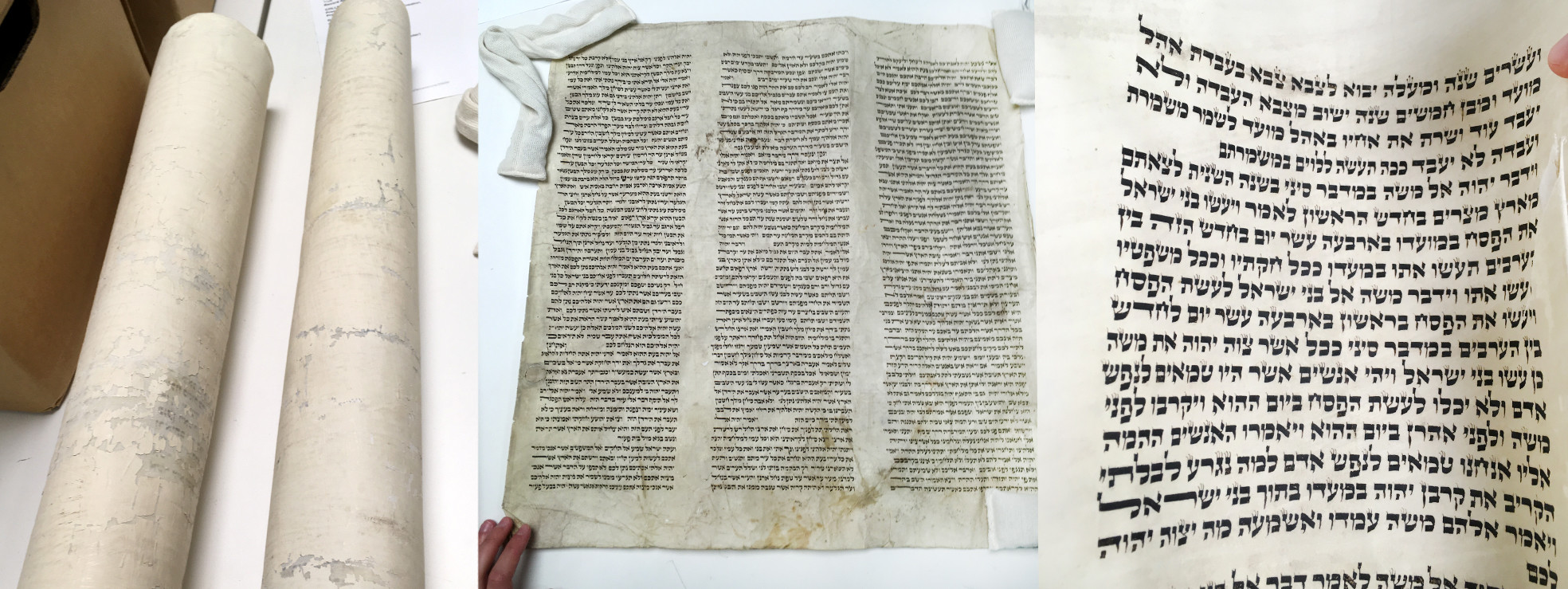

The older of the three Sefer Torah fragments, likely from the 18th century, is on thinner parchment and shows wear, discoloration, and damage along the bottom edge.

The shorter of the three fragments, 58 x 67 cm, is a thinner, more supple parchment, characteristic of the 18th century. The manuscript fragment consists of three columns of justified text of 52 lines. The text begins in the middle of Deuteronomy, chapter 1 verse 8 and continues through the end of Deuteronomy, chapter 4 verse 3. The right column includes a patch repair in the middle of chapter 1 verses 28 and 29. Some letters are faded and or chipped and the parchment is stained and shows wear and creasing on the top and bottom edges which may be a hint as to why it is now longer part of a full scroll.

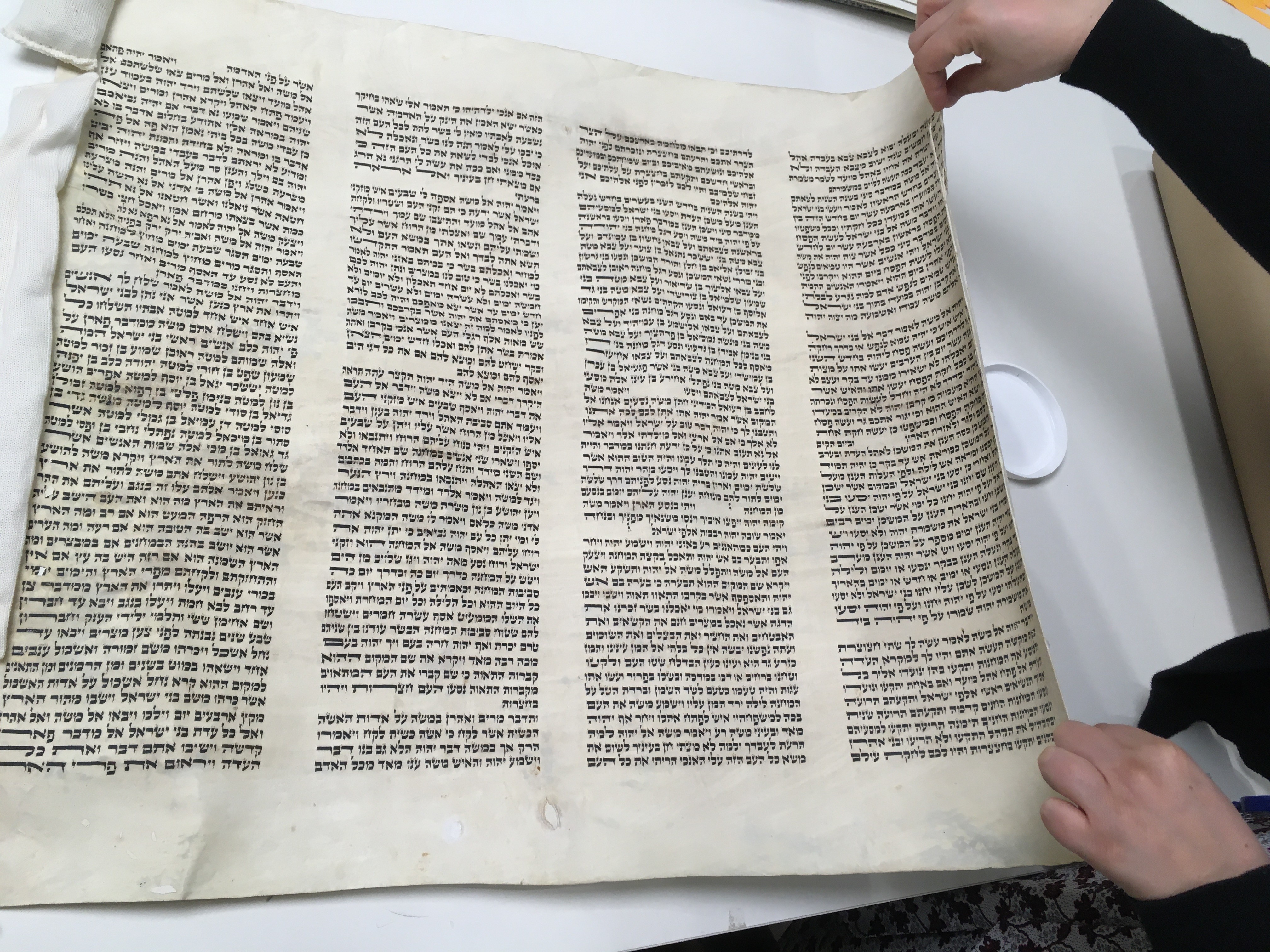

The two 19th century fragments are on a thicker parchment with a white flaking glazing on the verso which makes the parchment stiff and difficult to unroll. These pieces require careful handling and weights to view and will likely require some conservation work or special housing before they can be used in the reading room.

Two of the fragments, likely from the same scroll, have a white glazing on the verso that is crumbling and flaking. The glazing may have been added to make the parchment appear whiter, or to stiffen it, and was used beginning in the mid-19th century but the practice has since been discontinued. These fragments measure 58 cm high and the larger piece is 67 cm wide and includes four columns of text, 54 lines each. The smaller of the two fragments shows just one full column. This fragment had been cut in the middle of the two adjacent columns which may indicate that the fragment was likely cut from a discarded parchment sheet or from a stolen and dismantled scroll. The larger fragment begins in the middle of Numbers, chapter 8 verse 24 and continues through Numbers, chapter 14 verse 26. The text of the smaller fragment begins at the end of Deuteronomy, chapter 14 verse 27 and continues through the end of Deuteronomy, chapter 16 verse 13.

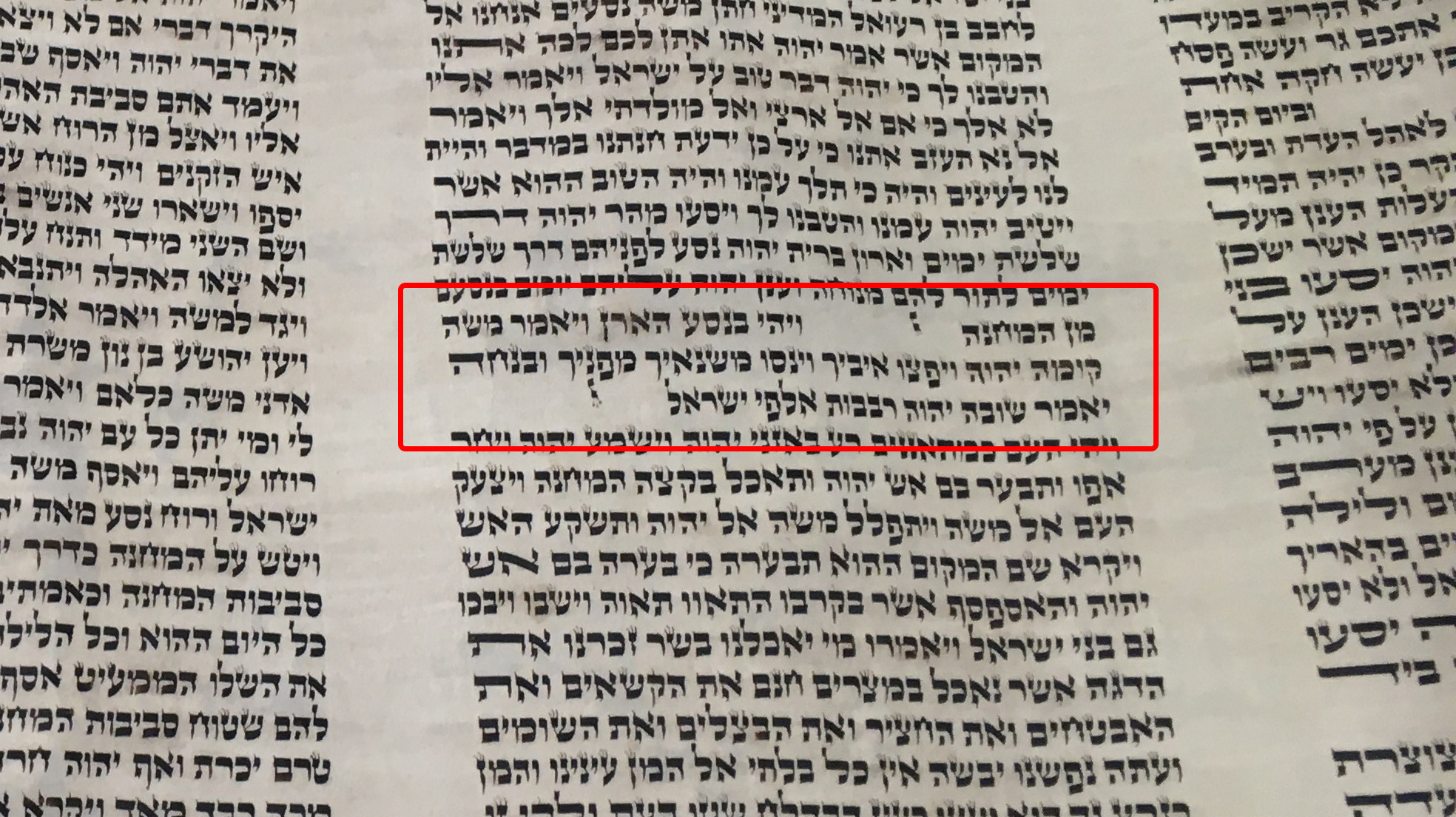

A detail view of the larger of the two 19th century fragments. This piece includes Numbers, Chapter 10, verses 35-36 (circled in red), indicated by “inverted nuns” which have traditionally been used as critical marks in Torah scrolls for millenia.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Annie Norman-Schiff, Yale University PhD candidate in Religious Studies, and to Rabbi Levi Selwyn of Sofer on Site for their assistance with research and subject expertise.