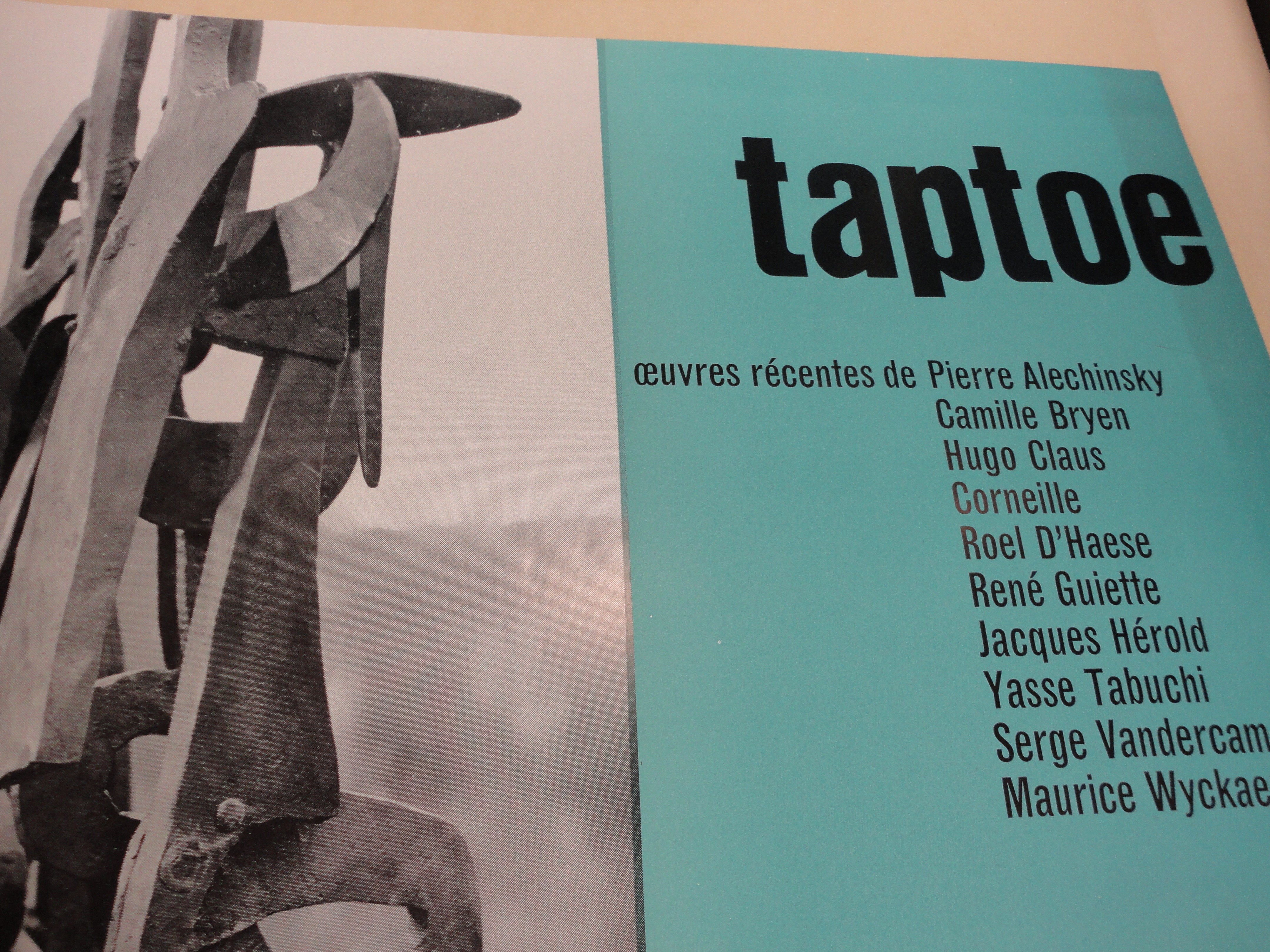

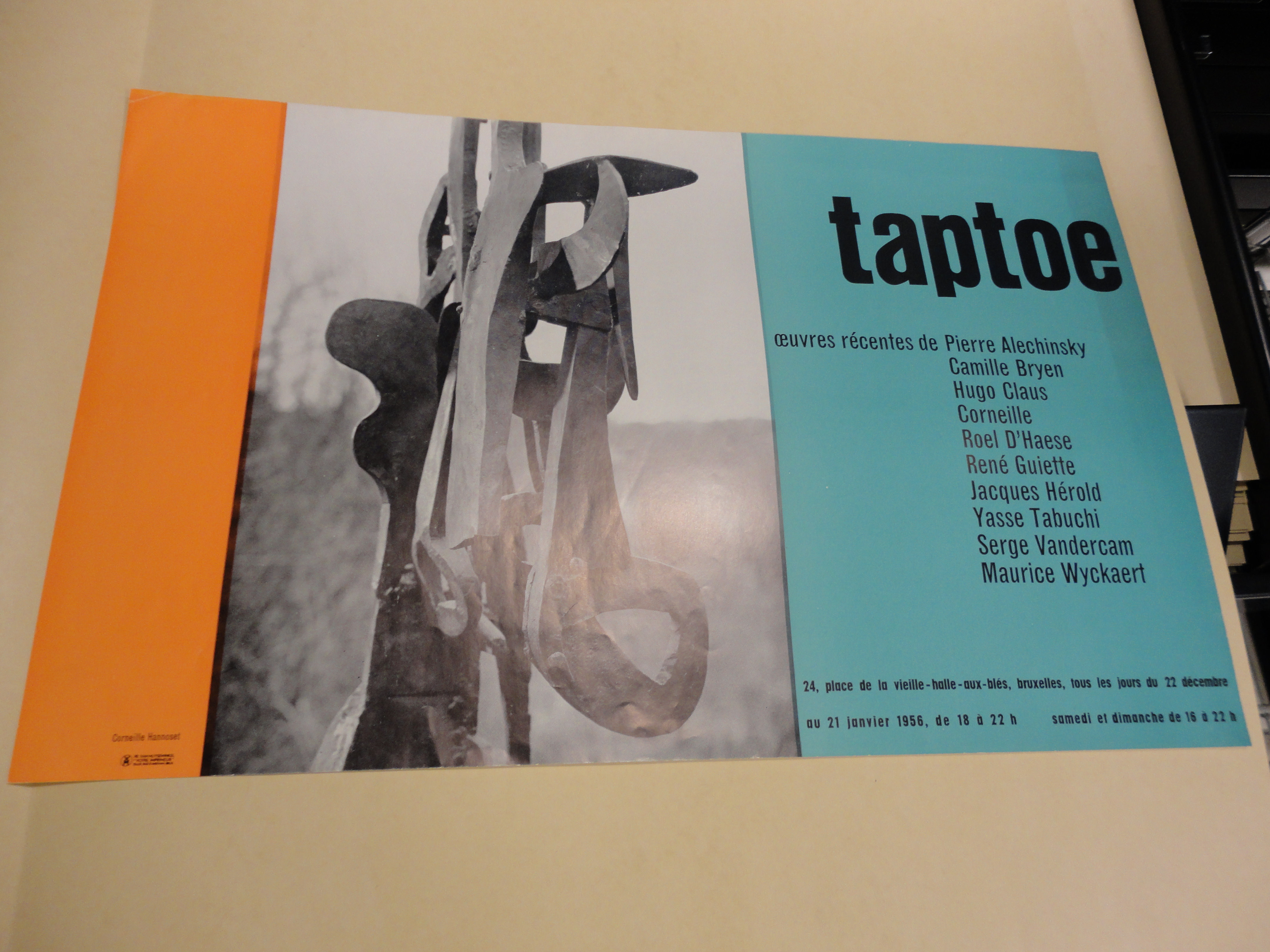

Flier for very first show at Taptoe, December 22, 1955

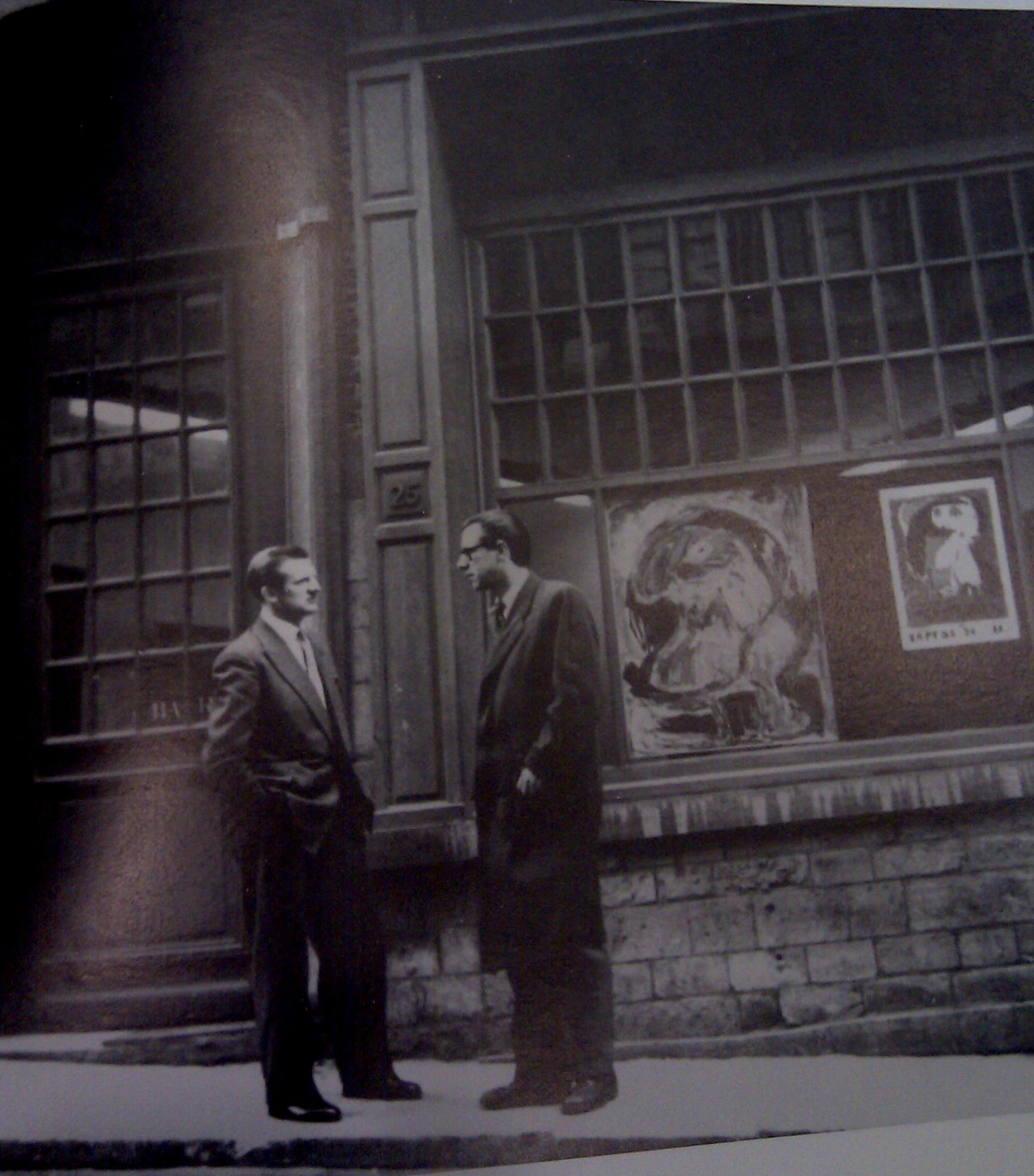

Beinecke has recently acquired a near complete collection of posters, catalogues, and ephemera related to the short-lived but influential Taptoe Gallery in 1950s Brussels. A “center for the arts,” Taptoe opened its doors in 1955 under the direction of Gentil and Clara Haesaert. In addition to an exhibit space, Taptoe had meeting rooms, a bar/cafe, and beds, a setting ripe for the sort of heady pow-wows one could expect from wandering avant-garde artists. They featured poetry readings, jazz concerts (Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins), and conferences (one titled “Architecture is a Crime that Pays”), and anthropology lectures. As it was, Taptoe was one-of-a-kind in sleepy Brussels–a cultural “desert”–despite its proximity to such progressive centers of artistic activity, Paris and Amsterdam. As Corneille Hanozet remembers, “It is hard to believe that in Brussels in the 50s it was extremely rare to find a simple place to get to know one another and express ourselves.” (Taptoe)

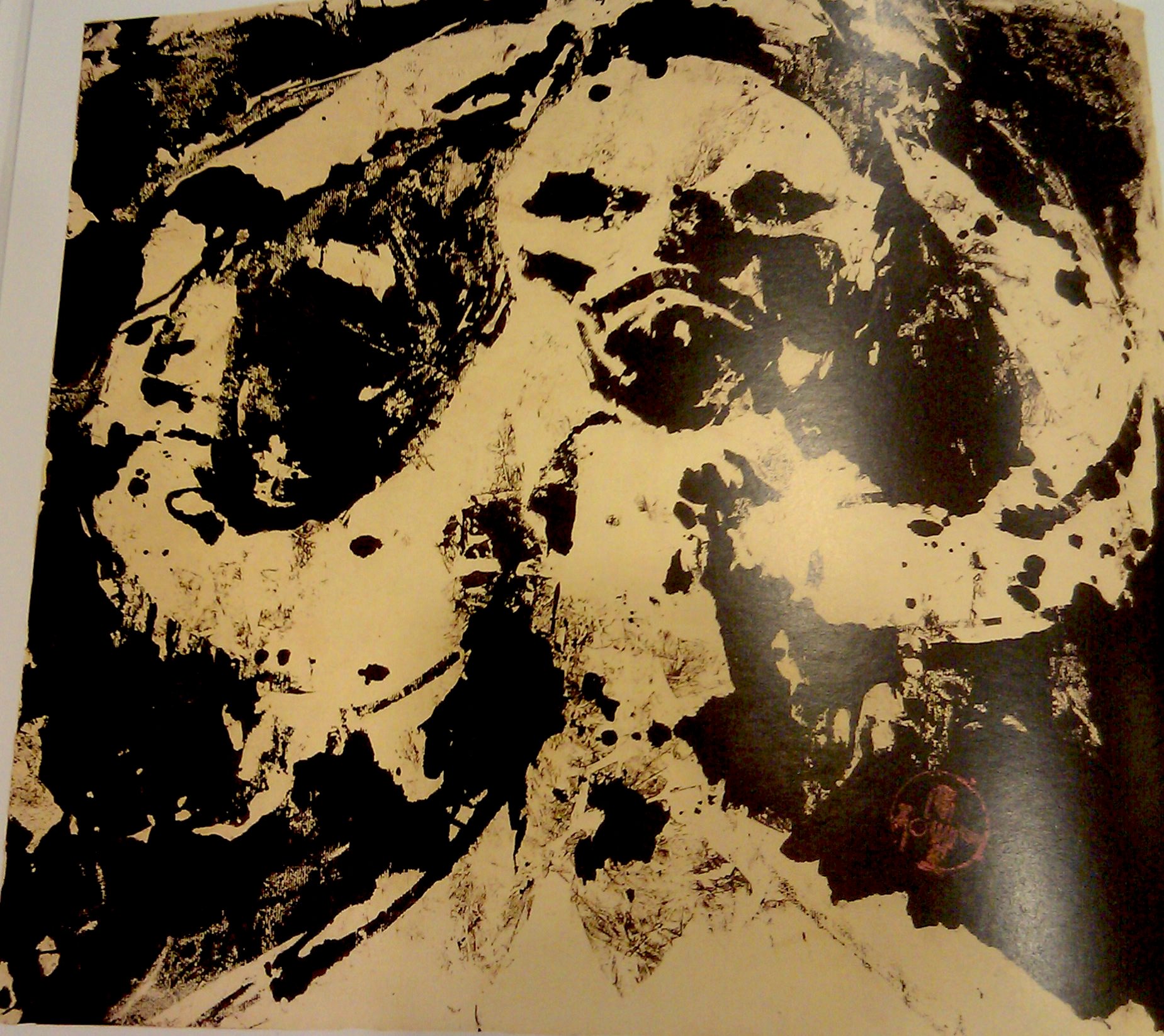

Close-up, another exhibition opening invitation

Taptoe took its name from Piet de Groof’s (a.k.a. Walter Korun) short-lived and irreverent poetry revue/comic book from just a few years prior. He had decided on the name because of its bilingual resonance in French and Dutch–an apt quality for a Belgian enterprise–though curiously, “taptoe” is not a French word. (Further confirmation that one must take de Groof’s retellings in Le général situationniste with a grain of salt.) In Dutch it means “tattoo,” not the kind you’re thinking of, but a military curfew–the drumbeat or bugle sounding for soldiers to repair to their garrison for bed. More generally, it can mean the last call, the final gong, that’s enough. De Groof was a celebrated Belgian aviator before turning to poetry, which explains his familiarity with the term. In 1955 as his Taptoe periodical began to lose steam he signed over the moniker to Gentil and Clara Wyckaert, then editors of De Kunst-Meridiaan, for their new gallery. Thereafter he joined the ranks as contributing member.

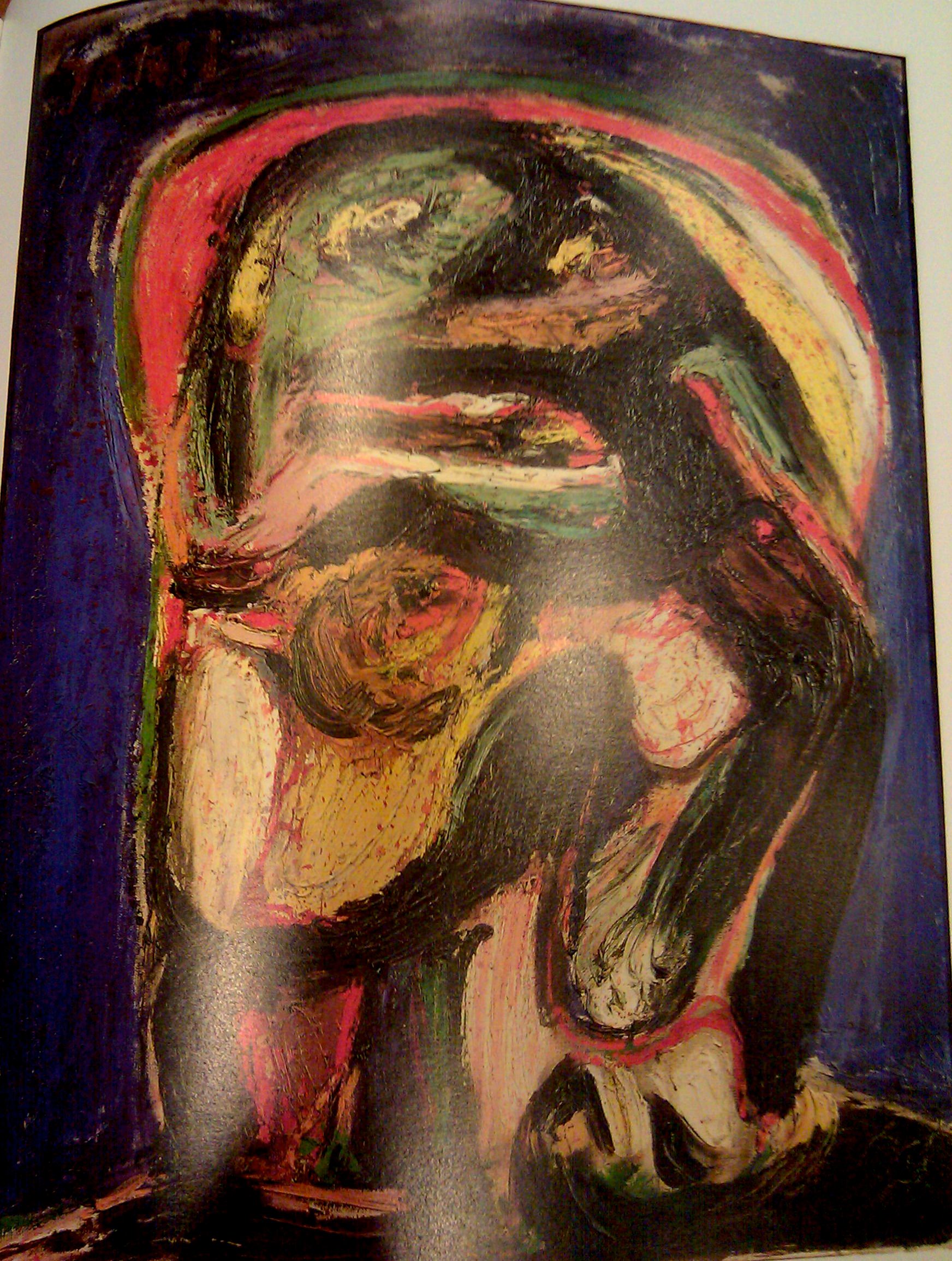

Taptoe set out to revitalize Belgium’s avant-garde. As a site for both national and international artistic dialogue Taptoe began to combat the sentiment that the Belgians were merely derivative of the Paris scene: Taptoe “reacted to and opposed the ‘official’ avant-garde imposed and protected by higher authorities.” (Le general situationniste) The gallery’s first two group exhibitions were runaway hits, surpassing all expectations. With paintings by Pierre Alechinsky, Hugo Claus, Serge Vandercam, Corneille, and sculpture by Reinhoud d’Haese, one critic avowed, “We must applaud Taptoe’s efforts of the last few months to pull from the shadows some of the most audacious works of art of today. These exhibits prove that art continues on its adventure despite initial hesitations.“ (Taptoe, Corneille Hanozet) Taptoe went on to feature Asger Jorn, Walasse Ting, and Paul Snoek in solo exhibitions. In February 1957, a now historic exhibit on Psychogeography played a role in catalyzing contact between Jorn and other future founding members of the Situationist International.

Post CoBrA and before SI, Taptoe came at an important moment, providing a venue for its most influential members during a crucial point in their evolution. So what, in keeping with the name, were they signaling the end of? Like other “counter-culture” movements of the post-war period, European artists needed to shed the heavy burden of the war, and with it, the ancien regime. According to de Groof, “We had to invent something for ourselves. All of a sudden everything was lighter. Our generation is … responding much more to our own aspirations. A new life is opening to us.” (Le general situationniste)