By Kendra Brewer

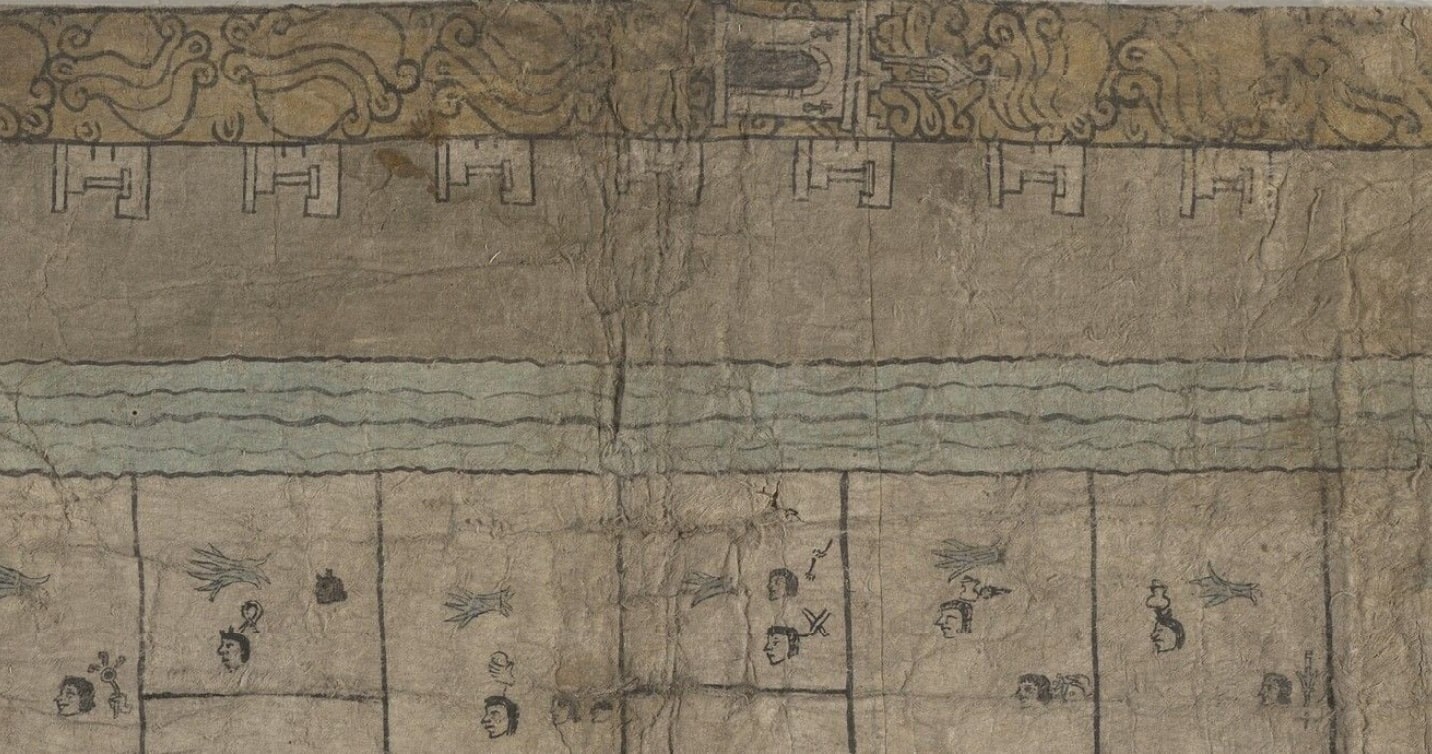

When we say a picture is worth a thousand words, we seldom mean that literally. But, for the Nahua, like many people living in Mesoamerica, text and images are closely connected. This connection is evident in the Codex Reese, a map of an area in or around Tenochtitlan (now called Mexico City) created in the latter half of the sixteenth century. This document, also known as the Beinecke Map, measures 72.5 by 177.5 centimeters and is made of several joined sheets of maguey-fiber paper. It represents a total of 121 plots of farmland, each evenly sized and clearly separated by a thick black border. Most of these land plots are marked with information about their owners, histories of land inheritance, and the crops grown on them.

Tlacuiloque, a Nahuatl term for people who are both artists and scribes (singular: tlacuilo), marked this information using symbols rather than letters. Most of these symbols, commonly called glyphs, had several, related meanings, partially because this writing system has no set reading order. People could (and still can) read entire histories and complex myths through just a handful of these glyphs. Documents like the Codex Reese should be read with this adaptability in mind so that they can be understood more fully. The dynamic nature of reading these codices is complemented by the Nahua understanding of mark-making itself. While English speakers use two terms to differentiate writing from painting and vice versa, in Nahuatl these practices are treated as one, shared category. The Nahuatl word cuiloa translates most closely as “to write-paint-record.” Because there is no distinction between painting and text in the Nahuatl language, the distinction between so-called proper writing (what linguists define as a representation of spoken language) and images was not as clear for Nahuatl speakers, if it existed at all.

Taken at face value, the imagery/writing of the Codex Reese depicts an orderly, unified community. A church with a single bell tower appears alongside a line of seven white houses in the top margin of the map near the right corner. These houses may refer to the kinship lines of the community rather than indicating that all 143 people depicted on the map lived together. A line of tetl (rocks/stones) is shown beneath the church while a canal or river of flowing atl (water) appears opposite. Taken together, these glyphs can call to mind the phrase in atl, in tepetl (literally “the water(s), the mountain(s)”), a metaphor for both a place and the people of that place. The community represented on the map is watched over by a series of Tenochca (a term for someone from Tenochtitlan) and Spanish rulers pictured in the map’s left margin. This line of rulers, all of whom reigned during the early colonial period, is only the most explicit reference to sixteenth-century colonialism in a map that depicts a fundamentally colonial world. The rulers’ calm, collected appearances reflect the overall orderly nature of the scene and the extent of their control.

The reality of life in sixteenth-century Mexico was far less orderly. Invasive species from Europe and the destruction of water management systems as a deliberate act of warfare were creating drastic ecological changes and wreaking havoc on people’s daily lives. Waves of epidemics were claiming lives of Indigenous individuals by the tens of thousands. Colonizing forces—both the Spanish government and the Catholic Church alike—were perpetuating physical and cultural genocide on an unprecedented scale, destroying lives and livelihoods with equal measure. Why, then, does the Codex Reese present this community as orderly amidst such upheaval? The answers are embedded in the thousands of words within this picture if only we take the time to read them.

A student research post from the Fall 2024 graduate seminar The Mind of the Book (HSAR 620). More information and link to other research posts.