John James Audubon: Birds of America

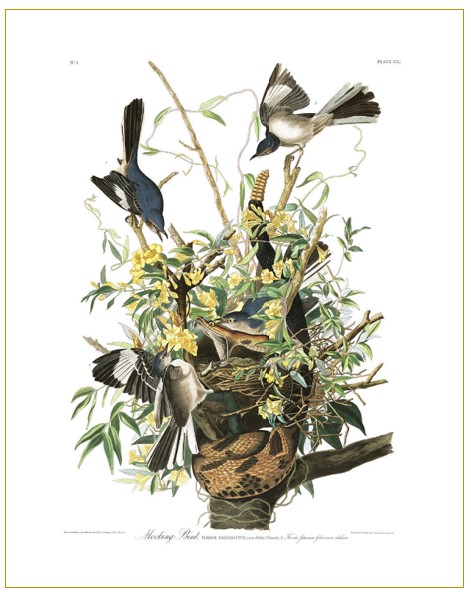

Plate 21, Mocking Bird

Published in London beginning in 1827, John James Audubon’s The Birds of America is extraordinary in several ways. The enormous 4 volume “Double Elephant Folio” carefully and accurately documents 435 species of American birds in life-size prints, making it an important work of natural history and scientific observation. Based on Audubon’s dynamic original paintings, each image was printed from an etched copper plate, and each print was then hand-colored with watercolor paints. The resulting plates are recognized for their uncommonly beautiful representations of the natural world and as exceptionally fine examples of 19th century etching and printing technologies. Accompanied by a five-volume textual account of Audubon’s observations and adventures, Ornithological Biography, or, An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America, the work’s scope and scale make it truly unique.

Yale’s two complete sets

It took more than 13 years to complete the 435 color plates that compose The Birds of America. Over that period, Audubon would cross the Atlantic several times and mounted expeditions in American woodlands to observe more species and make more watercolors. Fewer than 200 full-sets were produced. Of the roughly 120 complete copies now known to exist, Yale owns two.

Individual subscribers were responsible for assembling the color plates and binding them into volumes. Some subscribers died and others cancelled their subscriptions, meaning there were incomplete sets created.

The Beinecke Library additionally houses a treasure trove of Audubon’s correspondence, journals, and other writings.

About John James Audubon (1785-1851)

Audubon was born in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) in 1785, the son of a French naval officer and his Creole mistress. After his mother died while he was an infant, Audubon was brought to France and raised by his father’s wife. He developed interests in drawing and birds at young age. When he was 18, Audubon was sent to his family’s estate near Philadelphia to avoid conscription into Napoleon’s army.

He married Lucy, a neighbor in Pennsylvania, and settled in Kentucky, establishing a dry-goods store in Louisville that eventually failed. He spent years moving from Kentucky to Ohio to Louisiana pursuing various ventures before going bankrupt in 1819. With few prospects, he began his quest to paint America’s birds. He spent the next several years roaming the woodlands along the Mississippi River observing and drawing the birdlife. He would dispatch the birds and string them up into lifelike poses using elaborate armatures of wire and wood. Before modern photography, this was the surest method for making accurate drawings of wildlife.

By 1825, Audubon had gathered enough material to begin publishing The Birds of America. The project’s scale and complexity frightened away the few engravers in the United States equipped to make color-plate books. Audubon crossed the Atlantic with the 160 or so watercolors he had completed. William H. Lizars, a printer based in Edinburgh, agreed to take on the project. The first plate showed the wild turkey, which Audubon depicted strutting regally.

Labor issues forced Lizars to quit the project after he completed 15 plates. Audubon hired Robert Havell, a distinguished London-based printer, to finish the job.

The project was financed through pay-as-you-go subscriptions. Every few months, subscribers would receive a package of five prints: one large bird, a medium-sized bird, and three smaller birds. It was an expensive enterprise. A complete set of The Birds of America cost subscribers about $1,000. Many of Audubon’s subscribers were European aristocrats (American subscribers included U.S. Senator Daniel Webster). He spent much of his time in Europe courting potential subscribers in the salons of London and Paris, dressed in bearskin cloak, playing the role of the eccentric American woodsman.

Artistry and natural science

The 435 plates depict a total of 1,055 birds. Each plate tells a story in vibrant colors and rich details. Some of the stories are dramatic.

For example, plate 21 (shown above) depicts four mockingbirds battling a rattlesnake in a treetop. The snake bares its fangs. The birds look poised to defend their nest at any cost.

Such dynamic scenes provoked Audubon’s critics, accusing him of scientific inaccuracies. Many questioned whether rattlesnakes climb trees (they do). Or they argued that Audubon was attributing human behavior and emotions to animals. Audubon countered that he drew the birds as he had observed them in the wild.

The plates’ backgrounds, most of which were drawn by other artists working with Audubon, were an uncommon feature at the time. Most illustrators of natural history depicted specimens against a field of white.

The Birds of America features several bird species that have gone extinct or are considered close to extinction, including the ivory-billed woodpecker, Carolina Parakeet, Bachman’s warbler, Eskimo curlew, and passenger pigeon.

Revisiting Audubon’s legacy

Celebrated as a self-taught artist and naturalist of unrivaled accomplishment, Audubon’s name has long been associated with environmental conservation and citizen science. Until recently, many historians and biographers glossed or ignored facts about Audubon’s life that complicate well-known narratives: through the course of his life, Audubon enslaved as many as nine people of African descent and was dismissive of the work of Abolitionists in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Audubon has frequently been described as a fabulist and a teller of tall tales; such language has obscured or excused his sometimes-questionable scientific practices (including at least one example of outright dishonesty).

The Birds of America

The Lost Birds of Audubon