German Literature

The German Literature Collection contains rare books and first editions from the seventeenth through the nineteenth century. The William A. Speck Collection is one of the finest Goethe libraries outside Germany, while the Faber du Faur collection of German baroque literature has long served as a bibliographical source in its field. Lessing, Schiller, Heine, and Rilke have been collected in depth. Manuscripts include the papers of Hermann Broch, correspondence of the Kurt Wolff Verlag, Thomas Mann manuscripts and letters, and materials relating to Goethe.

Introduction

Like many library collections at Yale, the origins of the Collection of German Literature reach back into the history of the University. In the late decades of the nineteenth century, German book collecting was encouraged by Yale officers and faculty who had received their graduate education in Germany. Alfred Lawrence Ripley, 1878, for example, who taught German at Yale after studying in Berlin and Bonn, took particular interest in the Library during his thirty-four years as a Fellow of the Yale Corporation. University Librarian John Christopher Schwab, 1886, grandson of the German author Gustav Schwab, encouraged several programs to increase Yale’s German holdings.

Given this atmosphere, it is not surprising that Yale sought out William A. Speck, 1914 Hon., a German American pharmacist from Haverstraw, New York, who by 1913 had amassed the largest private Goethe library outside Germany. The collection was acquired for Yale, and Speck served as its curator for the rest of his life, adding books and manuscripts with funds provided largely by the University. By the time he died in 1928, the Speck Collection had tripled in size to embrace some twenty thousand books and as many prints, manuscripts, broadsides, and miscellaneous materials. For the next three decades, the Speck Collection was overseen by Carl F. Schreiber, 1914 Grad., whose double role as curator and Yale professor forged an especially close alliance between the Library and German literary studies at Yale.

By establishing the Library’s interest in German literature, the Speck Collection served as a beacon that attracted other materials. The Kohut Heine Collection came in 1930. Eight years later Thomas Mann founded a collection of his books and manuscripts at Yale, and in the 1940s and 1950s other authors and collectors exiled from Germany enriched the Library’s collections. In 1944, Yale acquired the Faber du Faur library of seventeenth-century literature, Faber serving as curator for the next twenty-two years and he in turn facilitated the acquisition of the papers of the publisher Kurt Wolff. Hermann Broch, who died in New Haven in 1951, bequeathed his papers to the German Literature Collection, and in 1957 a collection of Rilke’s printed works was added.

The year 1996–97 stands out as something of a recent annus mirabilis for the German Collection: just as the twentieth century was drawing to a close, the acquisition of two book collections launched a new program of collecting the literary works of those decades. The library assembled by Hans-Jürgen Frick, purchased on Beinecke funds, gave the German Literature Collection immediate bibliographic strength in the years 1900 to 1940 with special emphasis on Expressionist authors, while the Leslie Willson, 1954 Grad., gift of his Dimension library and archive set a collection development pattern for postwar literature.

Particular areas of strength in the German Literature Collection are described below:

Early Literature

The German Collection contains a small number of books published before 1600, including such rarities as the first folio edition of Hans Sachs (five volumes, 1558–79) and a copy of the original edition of Emperor Maximilian I’s Theuerdank (1517). German manuscripts, books, and pamphlets of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are found in abundance in the general collection at the Beinecke Library.

Seventeenth Century

The seventeenth-century holdings of the German Literature Collection, some twenty-nine hundred titles, have at their core the library gathered by Curt von Faber du Faur, a descendant of the publishing family Cotta and one of the founders of the Munich auction house Karl & Faber (now Hartung & Hartung). He began to form his library while he was a book dealer, and his collecting gained impetus during the preparation of the auction catalogue for the Victor Manheimer Collection in 1927, a project on which he collaborated with the poet Karl Wolfskehl. Faber came to the United States in 1939, going first to Harvard. Five years later Yale negotiated the acquisition of his book collection, offering Faber a curatorial position and a faculty appointment, both of which he held until his death in 1966. During his years at Yale, Curt von Faber du Faur augmented the collection in areas where his original holdings were relatively sparse–Catholic writing, Pietism, Jesuit drama, and Rosicrucianism. Many of these later additions were made through purchases from the library of the German scholar Richard Alewyn and through exchange with Professor Harold Jantz, whose collection is now at Duke University.

To suggest the scope of the Faber du Faur Collection, a few items might be mentioned here. There is an unusual group of song texts in the Italian style, by poets who were precursors of Martin Opitz’s reform of German poetics. The works of Opitz himself are well represented, as are those of the Nuremberg writers–Johann Klaj, Sigmund von Birken, and Georg Philipp Harsdörffer. The century’s most famous novelist, Johann Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, is represented by almost all the editions of his works published during his lifetime, including Trutz Simplex (1670), the source of Bertolt Brecht’s play Mutter Courage, and the only known perfect copy of the first edition of Das wunderbarliche Vogel-Nest (1672). There is a first edition of Johann Michael Moscherosch’s satirical Philander von Sittewald (1640), one of seven known copies. Faber gave special attention to collecting the works of the Viennese preacher Abraham á Sancta Clara; of the poet Johann Rist, author of still-familiar Protestant hymns; and of Christian Weise, who wrote novels and school plays. Johannes Praetorius, the eccentric recorder of Rübezahl and other folk tales, was the collector’s particular hobby. One of three known copies of Friedrich von Logau’s epigrams, Erstes Hundert Teutscher Reimen-Sprüche (1638), is present in the collection, as well as the scarce Kühlpsalter of Quirin Kuhlmann, with all four parts in one tiny volume (1684–86). Kuhlmann was a poet and religious fanatic who was burned at the stake in Moscow in 1689 as an enemy of religion and the state; one of his earlier projects had been a trip to Constantinople to convert the Sultan. Another rarity is a copy of the first printing of Paul Gerhardt’s Geistliche Andachten (1667), obtained from the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, which holds the other known complete copy of this compendium of hymn texts with music. Most of the volumes in Faber’s original collection are remarkably well preserved–the result of a watchful bookdealer substituting better copies as they came into his hands. The seventeenth-century portion of the German Literature Collection has been described in the two volumes of Curt von Faber du Faur’s German Baroque Literature (New Haven, 1958 and 1969), which, however, does not include the acquisitions of the last decades. Almost all of the twenty-five hundred titles listed in this bibliography are commercially available on microfilm from Primary Source Microfilm, a Gale imprint (formerly Research Publications, Inc., which issued a guide to the films in 1971, a volume that reproduced the Yale University Library catalogue records for the books). The collection is being augmented as aggressively as the market allows.

Eighteenth Century

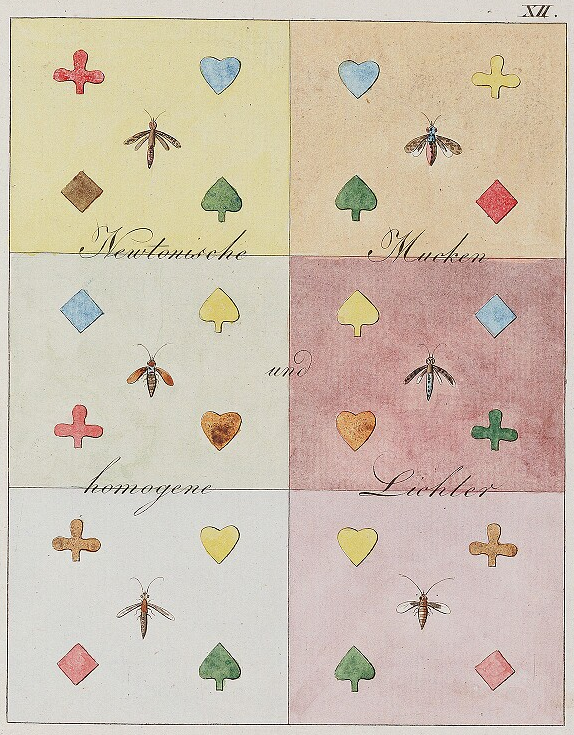

While Faber du Faur’s main collecting interest was the Baroque period, he nevertheless brought to Yale an outstanding group of eighteenth-century books, many of them illustrated editions. This core has been supplemented over the years by purchase and with transfers from Sterling Library. Large gatherings of works by the Hainbund poets–a group of nature enthusiasts centered briefly in Göttingen–stand beside contemporaneous rare items from the Sturm und Drang.

The cryptic philosopher Johann Georg Hamann, known to his contemporaries as the “Magus of the North,” is represented by an extraordinary set of early editions annotated by the author. Christoph Martin Wieland, whose multifaceted career spanned the second half of the eighteenth century; the playwright and novelist Friedrich Maximilian Klinger, who gave the Sturm und Drang its name; and the Swiss theologian Johann Caspar Lavater have been collected in depth. In addition to Lavater’s printed works, there are several substantial manuscripts and an intriguing collection of fragmentary manuscripts and physiognomic drawings, ostensibly castoffs from Lavater’s workshop, where he was in the habit of producing handmade books for his friends. Many of the Lavater relics in the collection came to Yale in the 1920s from family descendants, Waldemar C. Hirschfeld (Yale certificate in architecture, 1903) and his brother Robert Lavater Hirschfeld, both then of Meriden, Connecticut. The Hirschfelds also donated an oil portrait of Lavater by a little-known painter named Ilg, a portrait of the eighteenth-century satirist Gottlieb Wilhelm Rabener by Anton Graff, and a drawing of Mrs. Lavater’s hands by Heinrich Fussli.

Lessing

An extensive collection of printed works by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing came from three sources. Lessing titles held in the Speck Collection and those brought to Yale by Faber du Faur were supplemented in 1947 by 444 books and pamphlets by and about Lessing. The collection had been formed by Sigmund Schott, spoken of as “my late father” in a letter from George F. Schott, dated from Philadelphia in 1948. Around 40 percent of the Schott Collection, sold to Yale through the New York dealer Theo Feldman, was added to the German Literature Collection; the rest–duplicates and secondary literature–went to Sterling Memorial Library. The Beinecke Lessing collection now includes rare early works such as the comedy Die alte Jungfer (1749) and the first collected edition of his works, published in six volumes by C. F. Voss (Schrifften, Berlin, 1753–55).

Goethe

William A. Speck’s interest in Goethe dated back anecdotally to his boyhood reading of the play Götz von Berlichingen. Despite his fascination with Goethe, Speck trained as a pharmacist and worked in the family business in Haverstraw, New York. Every spare moment and penny, however, was devoted to Goethe. His collecting had two main thrusts: philology and biography. Because the critical edition of Goethe’s works, the 143-volume Weimarer Ausgabe, was then still incomplete, Speck felt compelled to amass every printing of every work by Goethe made during the author’s lifetime in order to document textual variants. On the other hand, Goethe the man and personality fascinated William Speck: he made several trips to Weimar, where he went up and down the streets and into taverns and boardinghouses in search of Goethe relics. He even brought back pressed flowers from Goethe’s garden and taught a course in Yale College about Goethe’s personality and physical appearance. The resulting collection has at its core an extensive gathering of Goethe’s works. Every collected edition issued up to 1832 (the year of Goethe’s death) is present, as is a full array of later, bibliographically significant sets. All of the Goethe first editions are held at Yale, along with almost all variants and later printings through the mid nineteenth century. There are extensive groups of translations of Goethe’s works, into both familiar and exotic languages. Illustrated editions have been collected, as well as fine press books.

Some of Goethe’s works have been collected in special detail. Faust, the principal example, is treated separately in this article. There is a great deal of material on The Sorrows of Young Werther, including English adaptations and parodies of the novel in prose, poetry, music, and prints. Many pre-Goethe versions of the beast epic Reynard the Fox are present. The German Literature Collection includes, as well, a growing number of literary annuals and almanacs from Goethe’s time. These volumes were originally collected because they contain suites of illustrations, contributions by Goethe, and first printings of works by other canonical authors. They have gained interest in recent years because they offer a cross-section of the literary tastes of the time, and because they preserve the work of women writers. Many include sheet music, while some contain fashion plates and ballroom dance diagrams.

Goethe’s life is thoroughly documented in biographies, editions of conversations and correspondence, maps, and prints; contemporary reaction to Goethe and his works may also be studied in detail. Materials relating to Goethe’s associates–his relatives, his friends, his amours, the personalities of the Weimar court–have been collected in depth.

The Speck Collection manuscripts include a few poems and quotations in Goethe’s hand, three original drawings by him, and a number of letters, some of them written by secretaries. The two most recent additions to this part of the collection are letters directed to one of Goethe’s scientific friends, Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner in 1812 and 1830; in the later one, Goethe asks for the chemical explanation of why a silver spoon soaked in a brew of red cabbage takes on a gold sheen. The Speck manuscript collection is strongest, though, in materials reflecting the British reception of Goethe. There are, for instance, autograph poems that Goethe wrote for the Carlyles and letters from Thomas Carlyle to Goethe’s friend and secretary, Johann Peter Eckermann, after Goethe’s death. Coleridge’s manuscript translation of the poem “Mignons Lied” is present, as are manuscripts by two little-known Faust translators: George Henry Borrow’s version of the “Walpurgisnacht” scene from Faust I and Jonathan Birch’s translation of Faust I and part of Faust II, published respectively in 1839 and 1843.

Many of the materials in the Speck Collection are listed in Carl F. Schreiber’s catalogue, Goethe’s Works with the Exception of Faust (New Haven, 1940). In pre-Depression days, this catalogue was ambitiously planned as a four-volume work, modeled on the three-volume catalogue of Anton Kippenberg’s Goethe collection, issued by the Insel Verlag in 1928. The second Speck volume was, of course, to have described Faust materials, the third volume would have listed biographical material on Goethe, while the fourth volume was to have brought addenda and a much-needed index. The illustrations and facsimiles for all four volumes were printed in Germany in the 1930s, but plans were never brought to fruition. The Faust volume has in all likelihood been eclipsed by Hans Henning’s massive Faust bibliography (1966–76), and the Speck catalogue, its title boldly announcing its own deficit, stands as a monument to different times.

Faust

Goethe’s Faust and Faust literature have been sought out by the Library since 1922 when William Speck purchased from the Zwickau collector George Wilhelm Heinrich Ehrhardt some six thousand items of Faustiana, including newspapers, magazines, playbills, and programs related to the theater history of Faust, as well as materials pertaining to the historical Faust and a large group of commentaries, parodies, translations, continuations, and critical studies of Goethe’s Faust, materials that supplemented, without extensive duplication, the twenty-five hundred Faust items Speck had already collected. From a different source, Speck acquired a fragment from act 5 of Faust II (“Offene Gegend”) in Goethe’s hand. The collection also includes several Höllenzwang manuscripts (conjuring texts such as the historical Faust might have used) and a group of nineteenth-century handwritten Faust puppet plays. Illustrated editions of Faust from both the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries are well represented.

Music

The Speck Collection contains many printed and manuscript scores, most of them from the nineteenth century, based on texts by Goethe or inspired by his works. Among the manuscripts are an early sketch from Wagner’s Faust Overture and a one-page fragment from Beethoven’s Egmont Overture. Liszt, Mendelssohn, Ludwig Spohr, and Goethe’s composer friend Karl Friedrich Zelter, among others, are represented by manuscripts. First editions of songs by Schubert and a copy of the “Leipziger Liederbuch” (a collection of songs published by B. C. Breitkopf in 1770 and said to contain the first appearance in print of a poem by Goethe) are highpoints of a large collection of printed songs, scores, operas, and libretti related to Goethe. Twentieth-century music has not yet been collected.

Theodor Hell

This group of about one hundred letters from the papers of Karl Gottfried Theodor Winkler provides a portrait of intellectual life in the age of Goethe. Under the pseudonym Theodor Hell, Winkler edited important periodicals, such as the Dresden Abendzeitung, and was a prominent theater director, playwright, publisher, and translator. Most of the letters in the collection were written to Winkler, but there is also correspondence exchanged by Wieland, Lavater, and Eliza von der Recke, famous in her time for her part in the exposure of Cagliostro. These letters came to Yale in 1938 as the gift of Mrs. Alfred E. Hamill, a niece of Winkler’s granddaughter.

Prints, Pamphlets, Ephemera and Artwork

The Speck Collection includes several vertical files of material that varies widely in value and rarity. Pamphlets, mostly material about Goethe, are classed and catalogued as printed books. In addition there are files of illustrations, chiefly to works by Goethe; portraits of Goethe and his contemporaries; and views of places associated with Goethe. These files were built strictly as subject collections, and material of the most ephemeral character stands side by side with such items as Piranesi’s views of Rome. Goethe’s travels are documented by a small map collection. Playbills and programs relating to productions of Goethe’s plays date from approximately 1850 to 1930. Files of Goethe postcards and of Goethe in advertising date primarily from the early decades of the twentieth century. Much of this material was gathered by a private collector in Berlin, Karl Berg, and was purchased from his widow in 1928.

The Speck Collection also contains a number of significant art works, such as the Oswald May portraits of Goethe and Wieland that hang in the Beinecke reading room, a bronze bust of Goethe by Christian Daniel Rauch, an engraving of the young Goethe by Johann Heinrich Lips, and an anonymous silhouette of the poet from 1786. A collection of about one hundred and fifty coins, medals, and medallions with likenesses of Goethe includes all but one struck during the poet’s lifetime.

Schiller

While Schiller has not been collected as thoroughly as Goethe, all of his first editions are present, including rare early works such as Anthologie auf das Jahr 1782, Venuswagen (1781), Wirtembergisches Repertorium der Literatur (1782–83), and Schiller’s dissertation, Versuch über den Zusammenhang der thierischen Natur des Menschen mit seiner geistigen (1780). A curiosity of the Schiller collection is the pamphlet Die Avanturen des neuen Telemachs, oder Leben und Exsertionen Koerners, fourteen colored sketches by Schiller that poke fun at his friend Gottfried Körner. The manuscript dates from 1786.

Women Writers

A special effort has been made over the last decades to add books by women writers of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, an area that had been neglected in the past. The German Literature Collection now has growing numbers of works by authors such as Sophie von La Roche, novelist, friend of Wieland, and mother of one of Goethe’s first loves; Benedikte Naubert, a prolific author of historical novels; the novelist and journalist Therese Huber; Johanna Schopenhauer, mother of the philosopher, novelist, and a figure at the Weimar court; Karoline Pichler, novelist and literary hostess in Vienna; Sophie Mereau, poet, translator, and novelist, whose second husband was Clemens Brentano; Sophie Bernhardi von Knorring, sister of Ludwig Tieck and the author of poems, prose, and criticism; and the poet Luise Brachmann, who drowned herself in the River Saale over an unhappy love affair.

Nineteenth Century

The German Collection is strong, although not complete, in first editions of the Romantic period. There are, for instance, copies of Friedrich Hölderlin’s Hyperion (1797–99), Clemens Brentano’s Godwi (1801–02), Novalis’s Heinrich von Ofterdingen (1802), Wilhelm Waiblinger’s Phaeton (1823), of the Kinder- und Hausmärchen (1812–15) of the brothers Grimm, and of the pseudonymously published Nachtwachen von Bonaventura (1805), now attributed to August Klingemann. The Library continues to add early nineteenth-century titles, such as Heinrich von Kleist’s Käthchen von Heilbronn (1810), Joseph von Eichendorff’s Ahnung und Gegenwart (1815), and Georg Büchner’s Danton’s Tod (1835). Literary editions from the second half of the nineteenth century, a growing collection at the Beinecke, are also present in Sterling Memorial Library, the result of the systematic purchase of German books begun at Yale during those decades.

Heine and Junges Deutschland

The basis of Yale’s Heine Collection, as well as a large portion of its holdings in Judaica, came from George Alexander Kohut. In 1915 Kohut gave to Yale his father’s extensive library of Judaica, the Alexander Kohut Memorial Collection, and in 1933 he donated his own Heine collection, which he had recently augmented by purchasing the Heine library of the Munich dramatist Arthur Ernst Rutra. The collection includes nearly all the printed works of Heine and representative manuscripts. It is especially rich in French editions and includes a historically significant gathering of works by the oppositional German writers of the 1830s and 1840s, with whom Heine is associated: Ludwig Börne, Theodor Mundt, Ludolf Wienbarg, Karl Gutzkow, and others.

Rilke

In 1957, Dr. Edgar S. Oppenheimer presented to the German Literature Collection a group of 186 volumes by and about the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Almost all of the first editions of Rilke’s works are present, including rare early publications (Leben und Lieder, 1894; Larenopfer, 1896; and the three issues of Wegwarten, 1895–96) as well as later limited editions. The collection is in mint condition and many of the volumes are specially bound. Oppenheimer (1885–1959) is better known as a collector of children’s books, an interest he developed after his immigration to the United States in 1941.

Kurt and Helen Wolff

Purchased in 1947, the Kurt Wolff papers consist of approximately 4,100 letters and some manuscripts from the files of the Kurt Wolff Verlag from the years 1910–30. During those decades Wolff was one of the leading publishers of contemporary literature in Germany, and his correspondents included Expressionists (Gottfried Benn, Georg Heym, Ernst Toller, Georg Trakl), Dadaists (Hugo Ball, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara), and artists (Paul Gauguin, Georg Grosz, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Käthe Kollwitz, Alfred Kubin, Frans Masereel) as well as such prominent literary figures as Gerhard Hauptmann, Hermann Hesse, Franz Kafka, Karl Kraus, Else Lasker-Schüler, Heinrich and Thomas Mann, Rilke, and Frank Wedekind. The longest files of correspondence are with Franz Werfel and with Walter Hasenclever, a friend from Wolff’s student days in Leipzig. In all, 178 correspondents are represented in the collection. Many of the letters at Yale were published by Bernhard Zeller and Ellen Otten in Briefwechsel eines Verlegers 1911–1963 (Frankfurt am Main, 1966).

After fleeing Europe in 1940, Wolff and his wife Helen established Pantheon Books in New York, which published the Bollingen Series and such popular works as the American edition of Doctor Zhivago and Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s Gift from the Sea. When Random House acquired Pantheon Books in 1961, the Wolffs were invited to join Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, where they had their own imprint. After Kurt Wolff’s death in 1963, Helen Wolff continued at HBJ, overseeing the Helen and Kurt Wolff Books until her death in 1994. In 1996 and 2003 Christian Wolff donated his mother’s papers, an archive that includes correspondence and other records from the early 1950s through the 1990s, reflecting Helen Wolff’s distinguished career as an international publisher based in New York.

Hermann Broch

The Beinecke Library’s Hermann Broch archive is the world’s principal repository of the manuscripts and correspondence of this exiled Austrian novelist and cultural critic. Broch’s road to New Haven, where he spent the last two years of his life, was itself the stuff of fiction. He was born in Vienna in 1886, the eldest son of a wealthy industrialist. His early training was in business and technology, and as a young man he successfully managed the family textile mills in Teesdorf, Lower Austria, rising to a position of considerable national prominence in the industry. Broch’s true interests, however, were in literature, art, and philosophy, and after the sale of the family firm in the late 1920s, he moved to Vienna and devoted himself wholly to writing. His Schlafwandler (Sleepwalkers) trilogy, a broad study of the decline of social and ethical values, appeared between 1930 and 1932, and by the late 1930s he had begun work on his last great novel, Der Tod des Vergil (The Death of Virgil), published in 1945. He died in 1951 and is buried in Killingworth, Connecticut.

Broch bequeathed his papers to Yale, and this core collection has since been richly augmented by purchase and by gifts of manuscripts, letters, and memorabilia from his family and friends. Virtually all of his books and essays are represented in manuscript form, most of them in multiple drafts, and the collection includes unpublished fragments as well as juvenilia, chiefly of a philosophical and mathematical nature. Broch was a letter-writer par excellence, and the archive contains a massive file of correspondence, both incoming and outgoing. Two recently added groups of central importance are his letters to fellow writer Franz Blei, and hundreds of letters to his second wife, Annemarie Meier-Graefe, from the 1930s to 1951. The archive contains a number of autobiographical documents, one of them only recently unsealed. Photographs of Broch have come from Broch’s family and from the photographers Trude Geiringer and Trude Fleischmann. Broch’s printed works (including a full range of translations) are supplemented by clippings and reviews that document the author’s reception to the present. Irma Rothstein’s bust of Broch and Peter Lipman-Wulf’s death mask of the novelist are also part of the archive.

Thomas Mann

At the core of Yale’s Thomas Mann holdings are nearly forty manuscripts given by Mann in 1938 for the purpose of establishing a collection. With the help and dedication of its advisor, Joseph W. Angell, the Mann Collection grew to include 102 manuscript items, about four linear feet of correspondence and special files, and a large collection of printed materials by and about Mann. Outstanding manuscripts include “Notizen zu Goethe und Tolstoi,” prepared for a lecture in 1921; the autograph manuscripts of the first two Joseph novels, Die Geschichten Jaakobs and Der junge Joseph; and 71 rejected leaves from the lost manuscript of Der Zauberberg. In addition to longer works, there are many essays, open letters, and speeches, especially from Mann’s time in the United States, for example, the autograph manuscript of the essay Dieser Friede, dated October 1938 from Princeton. The collection also includes the handwritten draft of Thomas Mann’s reply to Karl Justus Obenauer, who in December 1936 revoked Mann’s honorary doctorate from the University of Bonn, and a number of the Deutsche Hörer broadcasts in the form of typescripts corrected by the author. In 1957, Yale purchased the major portion of Helen Lowe-Porter’s Thomas Mann papers, including typescripts of her translations of essays and lectures by Mann and her English renditions of five of his novels, often accompanied by German typescripts, which were prepared under Mann’s supervision and have occasional manuscript corrections. Among the longer Mann correspondences held at Yale are the letters with Joseph Angell between 1935 and 1951, the letters to Hermann J. Weigand between 1927 and 1952 and to Helen Lowe-Porter, 1924–54. Erich Auerbach, Alfred Knopf, Llewelyn Powys, and Marguerite Yourcenar are represented by smaller groups of letters. The letters to Agnes Meyer, numbering over three hundred, offer indispensable information on Mann’s years in the United States. Mann met Meyer, wife of Eugene Meyer of the Washington Post