Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, from January 1776, and The American Crisis, from December 1776, are among seasonal selections on view in a temporary exhibit at the Beinecke Library this winter from December 13, 2019, to January 20, 2020, along with the pen used by Abraham Lincoln to sign the Emancipation Proclamation at the Executive Mansion, Washington, D.C., on January 1, 1863, and an announcement for a talk by Frederick Douglass on the Emancipation Proclamation at the Cooper Institute: New York, New York, 1863.

The Beinecke Library exhibition hall is free and open to the public daily; note: the library is closed for winter recess from Tuesday, December 24, 2019, through January 1, 2020. More information on daily hours can be found at the Hours and Accessibility page.

Winter 1776

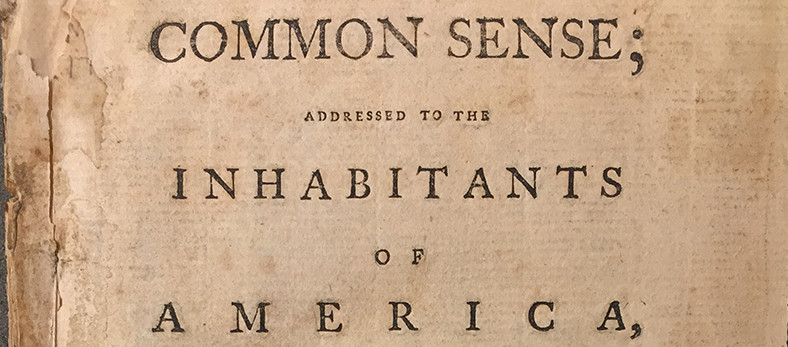

Paine first published Common Sense anonymously on January 10, 1776. A powerful argument for independence from Great Britain, the pamphlet was an immediate sensation, sold and read widely and, proportionate to the population of the colonies at the time, is the best-selling and most widely circulated title in American history. The full text of Common Sense can be found on the Project Gutenberg website.

Two copies of the pamphlet from the Beinecke Library are on view in this winter’s temporary exhibit. The title page of the first edition, printed by Robert Bell in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is on view along with an opening to pages in the second edition. The pages on view show some of the third section of the pamphlet, “Thoughts on the Present State of American Affairs.”

Joanne Freeman, Class of 1954 Professor of American History at Yale University, a leading historian of the politics and political culture of the Revolutionary era and early national periods of American history, reads a selection of the text from the original copies in a video on the Beinecke Library’s YouTube channel:

But where says some is the King of America? I’ll tell you Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Britain. Yet that we may not appear to be defective even in earthly honors, let a day be solemnly set apart for proclaiming the charter; let it be brought forth placed on the divine law, the word of God; let a crown be placed thereon, by which the world may know, that so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king.

Professor Freeman discusses Common Sense in depth in her course “The American Revolution” available online through Open Yale Courses. As she notes, “many scholars consider it to be the most brilliant political pamphlet of the Revolution.”

Paine began The American Crisis later in 1776, publishing the first of thirteen parts in the Pennsylvania Journal newspaper on December 19, 1776. It was very soon reprinted as a pamphlet by Styner and Cist in Philadelphia. The full text of The American Crisis can be found on the Project Gutenberg website.

George Washington read the inspiring work to the American soldiers on December 23, 1776. Professor Freedman reads the stirring opening lines of The American Crisis in a video on the library’s YouTube channel:

THESE are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.

Winter 1863

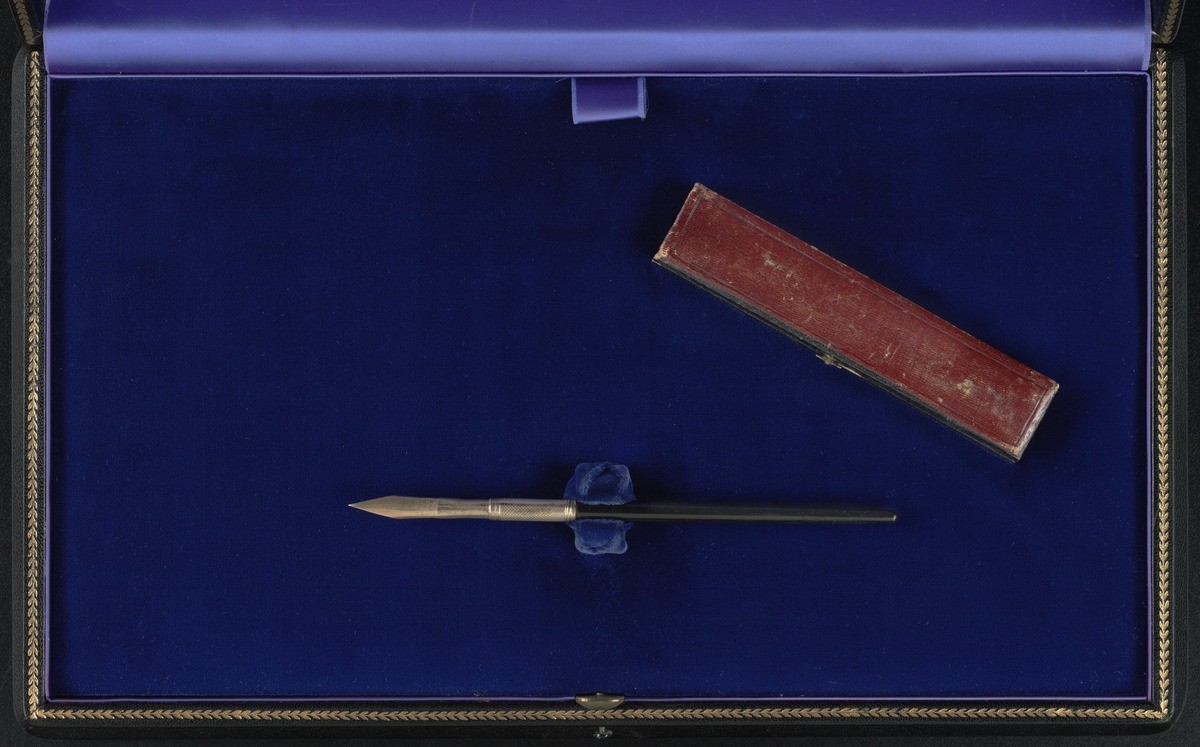

Two items from the winter of 1863 connected to the Emancipation Proclamation are also on view in the temporary exhibit, including a gold pen used by President Lincoln to sign the proclamation on the first day of the year.

A transcript of the proclamation can be found on the U.S. National Archives website. The National Archives says of the proclamation:

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, as the nation approached its third year of bloody civil war. The proclamation declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

Despite this expansive wording, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the United States, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy (the Southern secessionist states) that had already come under Northern control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union (United States) military victory.

An announcement of a talk by Douglass about the proclamation is displayed alongside the pen. It reads: “Frederick Douglass will talk on the President’s Emancipation Proclamation, and the arming of black men : Friday ev’ng, Feb. 6, 1863, at the Cooper Institute : admission 25 cents : platform tickets, 50 cents.”

The New York Times reported on the talk on February 7, 1863:

Mr. DOUGLASS was introduced by Rev. H.H. GARNETT, and spoke substantially as follows: He had come to talk to them of the greatest event of the century – of our whole history. That event was the fact that since the first day of January there had not been a slave in any State recognized as in rebellion against the Government, and that any slave had now the right to defend himself against the slaveholder as against a common robber. [Applause.] Assuming that the Proclamation of the President would be made good, it was impossible to conceive of a greater overturning by any nation, than would be occasioned. He hailed the Proclamation with joy, notwithstanding all that could be said against it. Our Star Spangled Banner now has a meaning. It affords shelter to all nations and all colors. He stood here not only as a colored man, a colored American, but as a colored citizen. The Attorney-General had announced that color is no disqualificaton of citizenship in the United States. [Applause.] We are all liberated – the black and the white – and the army is authorized to strike with all its might, even if it does hurt somebody. [Laughter and applause.] Mr. LINCOLN has dared to apply the old truth of human liberty to this time. He has dared to declare the truth of the Declaration of Independence. If adhered to, that truth will carry us through the struggle through which we are passing. [Applause.] As one who had been a slave, and bore upon his person the marks of Slavery, it was but natural that he should look at the Proclamation as a colored man. It was not only a mighty event for the bondmen and for the nation, but for the cause of truth throughout the world. Its advent would be ranked with Catholic emancipation, with the British Reform bill, with the repeal of the corn laws, the emancipation of 20,000,000 of Russian serfs, [applause,] and with every great event of history of a similar character. Though wrung out by the stern dictates of military necessity, it was in reality a moral necessity. We had been fighting the rebels with our soft white hands, and kept back our iron black hands. [Applause.]

David W. Blight, Sterling Professor of History at Yale and director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, writes in his 2018 biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom:

… the winter and spring of 1863 was a time for public glory, a time to reap all the possibilities of what Douglass called “the greatest event of the century”—the Emancipation Proclamation and the sacred history that flowed from it. The Final Proclamation included two significant changes from the Preliminary: it included no provisions for colonization, and it called for the recruitment of black men into the Union armed forces. The “destiny” of the American nation had changed forever, Douglass argued …

In January and much of February 1863 Douglass traveled more than two thousand miles from Boston to Chicago and many places in between, attending Jubilee meetings, cautiously anticipating the new war, the new history made possible by emancipation. His new standard speech was a tour de force of apocalypticism, moral philosophy, and a thunderous appeal for the enlistment of blacks in the army with equal status. The Proclamation, even with its limitations (freeing slaves only in the Confederate states or in occupied areas), brought about a world-historical moment, “a complete revolution in the position of the nation.” The republic was undergoing a second founding …