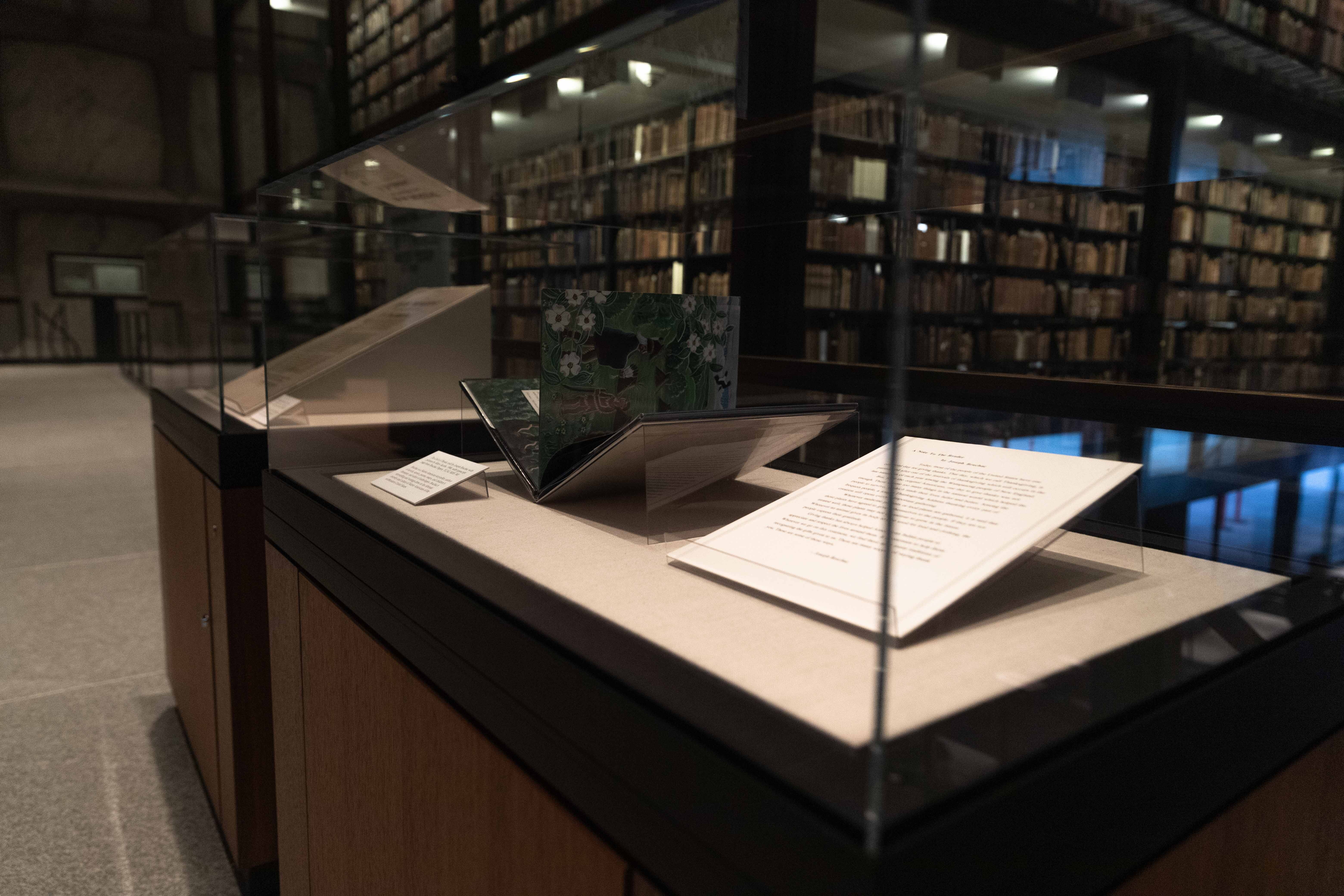

Words from George Washington, in 1789, and Joseph Bruchac, in 1996, offer two quite different views of Thanksgiving, as seen in a pop-up display on view now through December 3, 2019. Please note: the exhibition hall is closed on Thursday, November 28, and Friday, November 29.

The earlier document is a Thanksgiving Proclamation by President Washington, issued on October 3, 1789, that marked the first national celebration of a Thanksgiving holiday on Thursday, November 26, that year. The full text of the proclamation can be read online at the U.S. National Archives, which notes that only a few copies of the broadsides are known to exist today, including the one in the Beinecke Library collections. The one at Yale University is in the Jonathan Edwards Collection, GEN MSS 151.

Bruchac offers an enduring view of thanksgiving that dates much farther back in the lands that are now the United States in his book, The Circle of Thanks, illustrated by Murv Jacobs, on view in the pop-up display. Bruchac is an author of novels, stories, poems, essays, and children’s literature and editor of poetry and fiction anthologies. Bruchac’s storytelling and writings draw on his Abenaki ancestry and culture of Native Americans of the northeastern United States. Bruchac has been active in the Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers & Storytellers, and with his wife, publisher and editor Carol Bruchac, founded the Greenfield Review Literary Center and The Greenfield Review Press.

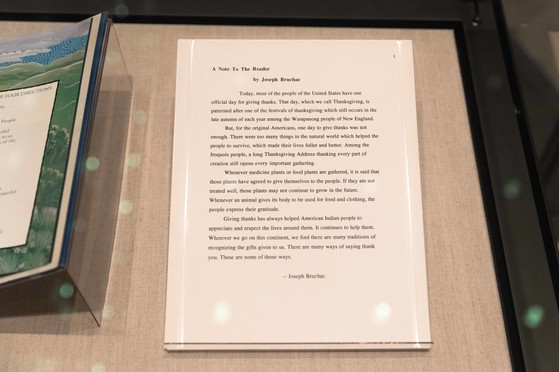

In a typescript of “A Note to The Reader,” on display and drawn from the Joseph Bruchac Papers in the Yale Collection of American Literature, he writes, in part:

Today, most of the people of the United States have one official day for giving thanks. The day, which we call Thanksgiving, is patterned after one of the festivals of thanksgiving which still occurs in the late autumn of each year among the Wampanoag people of New England.

But, for the original Americans, one day to give thanks was not enough. There were too many things in the natural world which helped the people to survive, which made their lives fuller and better. Among the Iroquois people, a long Thanksgiving Address thanking every part of creation still opens every important gathering.

All library visitors are strongly encouraged also to go to the Yale University Art Gallery, 1111 Chapel Street, to see the student-curated exhibition Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art on view through June 21, 2020. It is the first exhibition of Indigenous art to bring together objects from the Yale University Art Gallery, the Yale Peabody Museum, and the Beinecke Library.

Place, Nations, Generations, Beings “showcases basketry, beadwork, drawings, photography, pottery, textiles, and wood carving by prominent artists such as Maria Martinez (P’ohwhóge Owingeh [San Ildefonso Pueblo]), Marie Watt (Seneca), M.F.A. 1996, and Will Wilson (Diné [Navajo]), among others. Guided by the four themes in its title, the exhibition investigates the connections that Indigenous peoples have to their lands; the power of objects as expressions of sovereignty; the passing on of artistic practices and traditions; and the relationships that artists and nations have to animals, plants, and cosmological beings. The objects on view contribute to the larger narrative of American art and act as touchstones for further partnerships with Indigenous nations.”

Among its many holdings, the Beinecke Library collections include the papers of many contemporary Indigenous writers, including James Welch, Leslie Marmon Silko, N. Scott Momaday, Vine Deloria, and Bruchac. All are invited to search the library’s website and catalogs to learn more about these and all the collections and to learn more about how to engage with library resources.

Yale University acknowledges that Indigenous peoples and nations, including Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic, and the Quinnipiac and other Algonquian speaking peoples, have stewarded through generations the lands and waterways of what is now the state of Connecticut. We honor and respect the enduring and continuing relationship that exists between these peoples and nations and this land.