Pairing the Declaration and Douglass’s oration reflects the Beinecke Library’s appreciation that the ideals expressed in the Declaration were and remain aspirational. It gives an urgent summons to liberty and equality that so many who came before us worked to realize and that is now our work to follow.

With our colleagues on campus and our neighbors in New Haven, the library acknowledges all those who came before in this place and on these lands, especially the Quinnipiac people, who resided upon and stewarded these lands for centuries before English colonists arrived in 1638. We also acknowledge the history and continuing presence of the Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, and Niantic people who have stewarded through generations the lands and waterways of what is now the state of Connecticut. We honor and respect the enduring relationship that exists between these peoples and nations and this land.

We acknowledge that the founders of our nation were immigrants or descendants of immigrants who came to these shores without obstruction and faced no walls, no tests, and no detention camps. The foundation of this nation was the very embodiment of open borders. Many in the nation today are descendants of immigrants who came freely to this land.

We acknowledge the many immigrants who have come in more recent times to confront a system that contradicts the welcoming words inscribed on our Statue of Liberty. We acknowledge that thousands of children and adults are detained in camps on our nation’s soil and in our nation’s name.

And we remember that at this time 401 years ago, in July 1619, an English ship, the White Lion, was sailing across the Atlantic toward Jamestown, holding 50 or 60 enslaved people from the west central coast of Africa, the first of millions of people abducted, robbed of their freedom, sold, and transported to the present day United States in the brutal transatlantic slave trade.

We acknowledge all those millions of enslaved people brought to these shores against their will, we acknowledge their descendants, and we acknowledge the millions more who died in forced marches from their homes, in slave forts on the coast of Africa, or onboard slave ships.

We acknowledge Native Americans, immigrants, and the enslaved people brought to North America so that we can reckon with our past, in the present, to forge a better future.

The Declaration of Independence and Frederick Douglass’s 1852 oration are documents of our history that call across time for us to transform our imperfect present, with words and ideas to inspire us to action. As Douglass observed:

“We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future. To all inspiring motives, to noble deeds which can be gained from the past, we are welcome. But now is the time, the important time.”

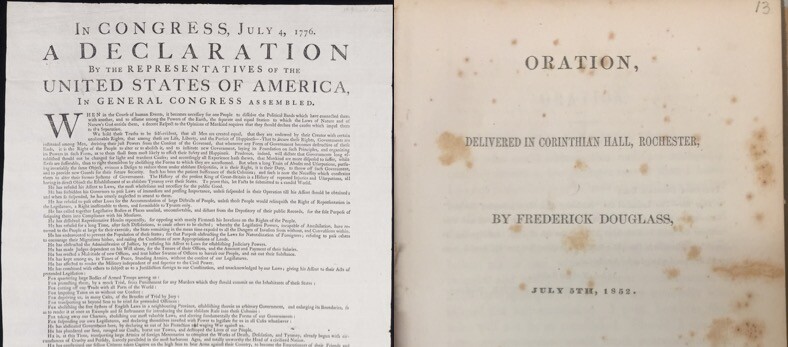

About the Dunlap Broadside, first printing of the Declaration of Independence

The Beinecke Library stewards one of the 26 known copies of the historic first printing of the Declaration of Independence. Often referred to as the Dunlap Broadside in honor of John Dunlap who printed approximately 200 copies in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776, the broadside was soon distributed throughout the thirteen states to announce the establishment of the new nation.

Read more in this 2017 story from the New Haven Register

About Douglass’s 1852 Oration

Frederick Douglass’s oration from July 5, 1852, is an essential speech for the nation now remembered as “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” The Beinecke Library stewards two copies of the first printing of the speech.

At once timely and timeless, Douglass’s oration is “the masterpiece of oratory of his life and the rhetorical masterpiece of American abolitionism,” according to David Blight, Sterling Professor of History at Yale University, Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, and author of the prizewinning biography, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.