Music in the Beinecke

Although it represents a numerically small proportion of the Beinecke Library’s some three-quarters of a million printed books and millions of manuscripts, music has recently come to represent a more and more significant part of the collections. It was not always so in the entire history of the Yale Library. Revealingly, there is no section devoted to music in its first printed catalogue, compiled by Yale president Thomas Clap in 1742 and published in New London the following year. One Psalm-Book is listed (was it the ninth edition of the Bay Psalm Book, published in Boston in 1698, the first one to contain music?), and one theoretical work on psalmody. They are not precisely identified, nor do they seem, in any event, to have survived, as no such titles are recorded in the reconstituted 1742 Library preserved on the ground level of the Beinecke glass tower.

The fact that sacred music needed advocates in colonial America is well documented in the Beinecke collections, with printed sermons entitled Regular Singing Defended (1728, by Nathaniel Chauncey) or The Nature, Pleasure and Advantages of Church-musick (1771, by Zabdiel Adams) and pamphlets such as The Lawfulness, Excellency and Advantage of Instrumental Musick in the Publick Worship of God Urg’d and Enforc’d (1763, by James Lyon). Yet it was in New Haven that there lived and worked one of the main artisans of the postrevolutionary American musical renaissance, Daniel Read, whose compositions first appeared in Simeon Jocelin’s The Chorister’s Companion, or Church Music Revised (1782) and, three years later, in his own American Singing Book, or, A New and Easy Guide to the Art of Psalmody (1785). Both books were printed in New Haven; both are in the Beinecke in several editions, as well as the three parts of Read’s Columbian Harmonist, published in 1793–95, and a number of subsequent editions.

Sacred music also occupies a distinguished place among Beinecke’s early books and manuscripts. To limit ourselves to Barbara A. Shailor’s Catalogue of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Beinecke Library, the first volume lists and describes ten items that are chiefly or significantly musical, to which one must add seven that are partially so (often only because of the presence of an unrelated music manuscript “recycled” as binding material); the second volume contains seven musical manuscripts, and four manuscripts with a partial musical component; and the third volume, devoted to the manuscripts that were collected for Yale by Thomas Marston, 1927, lists one important musical manuscript (the thirteenth-century Austrian missal catalogued as Marston MS 213). Among the great treasures of the collection, some of which were part of Barbara A. Shailor’s 1988 exhibition “The Medieval Book,” are MS 18 (a fourteenth-century French missal), MS 42 (a late fifteenth-century Florentine gradual), and MS 205 (a mid fifteenth-century processional that originated from a Dominican nunnery). Of the two secular music manuscripts, one is a series of sixteenth-century hunting calls (MS 200) and the other, MS 91, one of the world’s most celebrated collections of medieval songs, known as the Mellon Chansonnier after its last private owner, who presented it to Yale in 1940. This beautifully calligraphed manuscript on parchment, clearly Neapolitan in origin and dating from the mid 1470s, may have been prepared for the wedding of Beatrice of Aragon, daughter of the king of Naples, and Mathias Corvinus. In it are songs by two of the greatest names of medieval music, Johannes Okeghem and Guillaume Dufay. A third composer represented in the Mellon Chansonnier is Gilles Joye: the Chansonnier was last exhibited in Bruges as part of the exhibition commemorating the fifth centenary of Memling and was shown next to Memling’s portrait of Gilles Joye, now in the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth. Two medieval manuscripts with a musical component are to be found in the Mellon Alchemical Collection, also preserved in the Beinecke Library.

One would not necessarily associate the Beinecke with music theory, but the collections include three Greek manuscripts dealing with this topic (MSS 270, 271, and 272), all of them from late sixteenth-century Italy, as well as 23 printed items: the earliest, the 1501 Cologne edition of the Opus aureum of the Nancy-born Nicolaus Wollick (or Nicolas Wolquier, or Volcyr), as well as classics such as Vincenzo Galilei’s Dialogo della musica antica e della moderna, published in Florence in 1581, and the contributions to music theory by Descartes and Mersenne in the seventeenth century.

In addition to being Galileo’s father, Vincenzo Galilei was, as is well known, closely associated with the birth of opera. The field of opera is richly represented in the Beinecke’s collections, which have been considerably enriched in the past few years by important acquisitions, now being catalogued, in the field of sixteenth-, seventeenth-, and eighteenth-century Italian theater and theatrical performance. They document, for example, the tradition of the sacra rappresentazione in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—sacred dramas that were performed, with or without music, either publicly or in schools and monasteries (Racine’s Esther and Athalie being late representatives of this tradition). Most of these printings are of the greatest rarity; some of them are unique. The same applies to those documenting the use of music in secular ceremonies at the various Italian courts: they often are the only surviving trace of performances for which the music has been lost. One such loss is Monteverdi’s Arianna, but the Beinecke houses the first printing of the prose comedy by Guarini, L’idropica, which was performed at the same time in Mantua in 1608. More popular musical genres are also documented, such as Neapolitan songs, 128 of which, all pre-1650, are gathered in Primo[-duodecimo] fiore di villanelle, et arie napolitane (two editions: In Milano, per Gio. Battista Malatesta, [16–], and In Venetia, Appresso Domenico Imberti, 1607). At the other end of the spectrum are the opulent spectacles and stage machinery of the latter half of the century, illustrated for example in Giovanni Andrea Moniglia’s Delle poesie dramatiche, published in Florence in 1689–90. There is also a group of manuscript records relating to the Accademia degli Immobili in Florence in the 18th century: this society operated the Teatro alla Pergola and the records include a playbill for a 1718 production of a partially lost opera by Vivaldi, Lo Scanderbeg.

Of the special collections that were assembled under the roof of the Beinecke when it opened in 1963, the oldest was the Yale Collection of German Literature, one of the largest components of which is the Speck Collection of Goetheana. Given Goethe’s enormous influence on the music of the nineteenth century, its large musical component is not surprising. William A. Speck, 1914 Hon., indeed, collected every possible musical setting of Goethe—stopping short, however, and perhaps unfortunately, of the twentieth century (Speck died in 1928). The collection includes an early sketch of Wagner’s Faust Overture, a one-page fragment from Beethoven’s incidental music to Egmont (Claerchens Tod), and manuscripts by Reichardt, Liszt (Kennst du das Land?), Mendelssohn (Suleika, opus 57 no. 3, acquired from Oliver R. Barrett, a Chicago lawyer, by exchange for American presidential autographs), Carl Loewe, Spohr, and, inevitably, Karl Friedrich Zelter, Goethe’s infelicitous musical mentor. Schubert (Zelter’s chief victim insofar as his music failed to attract the master’s attention) is well represented in the collection of printed music relating to Goethe, which begins with the Leipziger Liederbuch of 1770, the first appearance in print of a poem by Goethe.

There are many settings of famous or less famous Goethe poems by lesser known composers: Moritz Hauptmann, Alfred Hertz, Johann Christoph Kienlen, Martin Plueddemann, Gottfried Preyer, Carl Friedrich Rungenhagen, Robert Volkmann, and Karl Friedrich Weitzmann, as well as a number of unidentified authors.

The collection includes many examples of musical adaptations of Goethe. Some are unexpected, for example Daniel-François-Esprit Auber’s Le dieu et la bayadère (adapted from the ballad Gott und die Bayadere), of which the Beinecke hold’s Scribe’s own copy; or Pugni’s ballet Satanella. The nineteenth-century treatments of Faust are all present, including all the obvious ones—Spohr, Berlioz, Schumann, Gounod—and the less obvious (Anton Radziwill). Of Gounod there are many editions in multiple languages, including parodies— like Hervé’s operetta Le petit Faust.

The collection of German Baroque literature formed by Curt von Faber du Faur also comprises a distinguished music component. Much of it is devotional, such as settings of Psalms, hymns, and religious poetry, one of the rarest items being Paul Gerhardt’s Geistiche Andachten of 1667. The Faber du Faur Collection also contains literary items with musical connections: thus the writings of Mariane von Ziegler, who provided Bach with texts for some of his cantatas, or those of Johann Beer, who under his own name was a well-known musician and writer about music while he published literary works under various pseudonyms. The two personae were brought together only in the twentieth century. His Bellum musicum oder Musikalischer Krieg, published in 1701, contains an imaginary map of the world of music.

The music component of the Yale Collection of American Literature is also large, comparatively speaking (more than fifteen hundred entries in the Yale online catalogue), and particularly interesting in its diversity. The most obvious category is music collected because of its literary connections: thus one finds innumerable settings of Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, Walt Whitman, Eugene Field, Emily Dickinson, Mark Twain, Ezra Pound, Eugene O’Neill, 1926 Hon., Archibald McLeish, 1915, H. D., Gertrude Stein. The collection also includes the papers of Paul Rosenfeld, 1912, music critic of The Dial, the great Modernist literary magazine of the 1920s, as well as part of the archive of the musicologist Mina Curtiss.

Mina Curtiss was the sister of Lincoln Kirstein and from her brother came an eccentric collection devoted to cats, which contains music. Not a certain musical one might have in mind, but such gems as Henri Sauguet’s ballet La chatte, Samuel Barber’s Hermit Songs, and Stravinsky’s Berceuses du chat for soprano and clarinet obbligato, dating from 1914 and marking his first collaboration with Charles Ferdinand Ramuz, with whom he later produced the much better-known Renard and L’histoire du soldat.

An important subset of the Yale Collection of American Literature, and a particularly rich one musically, is the James Weldon Johnson Collection of Negro Arts and Letters. Johnson’s own contributions to the music world are preserved in the collection, such as early editions of his “Lift Every Voice and Sing” or the English version of Granados’s opera Goyescas, first published in 1915. But more generally the collection documents African American music and musicians in the broadest sense from the mid nineteenth century: Bryant’s and Campbell’s Minstrels in the mid 1840s; music inspired by Uncle Tom’s Cabin or connected with Harriet Beecher Stowe; early settings of poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar; the career of Paul Robeson (35 titles in Beinecke and some actual recordings). There are archival collections relating to the National Negro Opera Company; to Zora Neale Hurston’s musical comedy Polk County; to the Charles H. Pace Gospel sheet music business; and papers of Gordon Myers relating to God’s Trombones.

One of the peculiarities of the James Weldon Johnson Collection is that it is not, or at least was not at the time of its inception, limited in scope to African American arts and letters. Thus the composer most prominently represented in its holdings is Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, the British composer known in his day as “the black Mahler.” The collection includes his immensely successful cantata after Longfellow, Hiawatha’s Wedding-Feast, premiered in 1898. Other composers represented in the Johnson Collection are hardly remembered today, such as Thos. S. Allen, who appears unknown to the New Grove Dictionary of Music.

The music component of the Western Americana Collection may not be the one immediately brought to mind by this famous collection but it is far from negligible. Its strength is, as one would expect, in popular music: patriotic or occasional music (“The Acquisition of Louisiana: A national song, Written by Michael Fortune; the music by an Amateur,” of about 1803); early ballads with a Western theme (“The San Francisco Rag-picker,” “The Dying Californian,” this latter in more than ten different printings) or with a Native American connection; religious music, such as hymnals and kyriales translated into Indian languages; instrumental works (“The Texian Grand March” from the late 1830s; “La Texiana, valse, composée pour le piano forte par W. V. Wallace” from the mid 1840s; “The miner’s quick-step, Composed for the Piano by A. F. Holmes”). Yet the collection also documents the rise of opera in the West: one can find, for example, a program for the opening night of the new opera house in Cheyenne, Wyoming (1882) as well as playbills for performances of Offenbach’s Pierrette and La grande-duchesse de Gérolstein (barely two years after the operetta’s premiere) by the Howson Opera in Salt Lake City in 1869. From one of the main godfathers of the Western Americana Collection came a group of 103 pieces, at this point not catalogued individually, of sheet music “by various composers and publishers” relating to the 1846–48 Mexican War. It should be noted that it is to the generosity of another of its godfathers, Henry Wagner, 1884, that the Beinecke owes its only early music manuscript from the new world, the mid sixteenth-century Mexican gradual catalogued as MS 480.

Music represents a quantitatively small, but qualitatively a very important part of the James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection. Osborn’s chief collecting interests being English, it is no surprise to find a number of early English music manuscripts among its holdings. The most famous, known as the Braye Lute Book, after the family from whose ancestral home (Stanford Hall) it was acquired, dates from around 1560 and, though only thirty-eight pages long, is considered one of the four primary sources of English lute music before 1570. (Its importance extends beyond the sphere of music, since one of the poems found in it turned out to be the ballad quoted by Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing, the source of which had perplexed and eluded scholars for more than two centuries.) Other English music manuscripts in the Osborn Collection include seventeenth- and eighteenth-century commonplace books and works by William Boyce, Benjamin Cooke, William Croft, George Frideric Handel (a full-score contemporary copy of Esther), and a number of anonymous works.

One of the best-known and most studied resources in the Osborn Collection is the correspondence of the father of musicology — in England and elsewhere — Charles Burney, author of The Present State of Music in France and Italy (1771), The Present State of Music in Germany, the Netherlands and the United Provinces (1773) and A General History of Music (1776). The collection contains letters from Johann Adolph Hasse, Joseph Haydn, and Christian Latrobe, among many others.

There is a particularly distinguished group of modern music manuscripts in the Osborn Collection: Benjamin Britten (autographs of the Michelangelo Sonnets and the Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra), Gustav Holst (the Choral hymns from the Rig Veda, the ode for chorus and orchestra, also inspired by Indian mythology, The Cloud Messenger), Ralph Vaughan Williams (the Serenade for Orchestra in A minor, the Heroic Elegy and triumphal Episode, and the cantata after Rossetti, Willow-Wood), and William Walton as part of a collective set of variations on the Elizabethan tune “Sellenger’s Round,” written for Aldeburgh.

Even though James Osborn was primarily interested, in his collecting of literary and historical manuscripts, in material relating to the British isles, the music component of his collection not only extends to non-English material, but it can be said that some of its most famous treasures are from the Continent. These include several Alessandro Scarlatti manuscripts, most notably the oratorio Il martirio di Santa Orsola and three volumes of cantatas, and an early nineteenth-century copy of Bach’s Violin concerto in A minor (it was then unpublished), presented by Felix Mendelssohn to Ferdinand David in 1841; there is even an intriguing Gounod manuscript, a dramatic scene set in Italian and clearly belonging to his years of apprenticeship in Rome. Best-known of all are the Gustav Mahler manuscripts acquired by James Osborn, whose wife Marie-Louise was an admirer of the composer’s music long before it became fashionable. The Beinecke therefore houses the autograph full-score of Mahler’s first important work, Das klagende Lied, the first part of which, Waldmärchen, was only rediscovered and premiered in 1970 (a draft of the poem for Das klagende Lied, in Mahler’s hand, was added, much later, to the collection); the holograph manuscript of the first symphony, with the original program titles, later discarded, for each movement, including the original second movement (Blumine), omitted by Mahler when he published the work; a fair copy, full-score, of the second symphony (the “Resurrection”), dating from after the premiere, abundantly corrected by Mahler (missing the fourth movement, the Lied “Urlicht”); a draft of the libretto of a never-composed opera, Rübezahl; and three annotated scores that document Mahler’s career as a conductor and, in particular, his editorial interventions and rewritings: Beethoven’s Eroica and Schumann’s first and fourth symphonies.

Several of the manuscripts just mentioned were acquired by the Beinecke after James Osborn’s death, thanks to the acquisitions funds he left for its development. One of the most important such acquisitions, made in 1998, formerly known as the Novello (now Osborn) Organ Book, a mid seventeenth-century Anglo-Flemish compilation by an unidentified English musician, containing more than a hundred compositions, among them two complete organ masses and many other liturgical pieces relating to the Roman Catholic ritual and therefore presumably intended for English recusants exiled in the Low Countries.

A new era for music in the Beinecke Library began in the spring of 1996 when Frederick R. Koch approached Yale, via its music librarian Harold Samuel, to become the permanent home for the collection of musical, literary, and historical manuscripts he had formed over the past fifteen years. Originally from Kansas, but a longtime resident of New York City, Frederick R. Koch was able to assemble in record time a collection that rivals in scope and splendor the finest institutional collections in this country.

One of the many exciting features of the Koch Collection, which made its presence at Yale particularly attractive, is the way it contrasts with, and therefore complements, the resources of the Music Library: the latter is particularly strong in early and baroque music and for archives of American composers and performers and twentieth-century émigré European composers; the former’s great strengths are in English, French, German, and Italian music of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

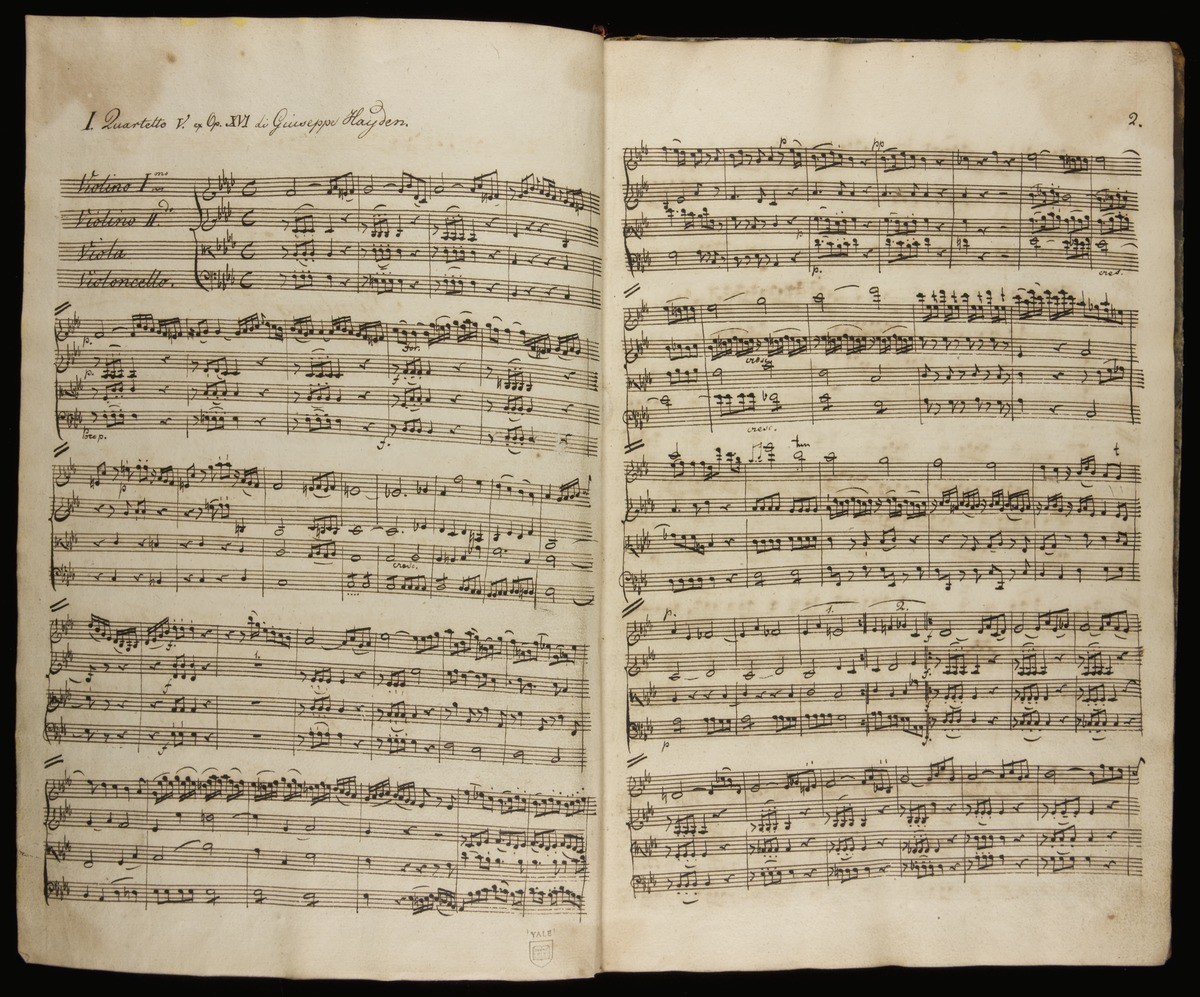

The Koch Collection contains, though, some prestigious pre-1800 manuscripts: an Album amicorum inscribed by Heinrich Schütz (in Latin: Heinricus Sagittarius) in Copenhagen in 1644; the only recorded manuscript of Handel’s so-called Roman Vespers of 1707, consisting of four anthems, complete in parts, written in the hand of a copyist with annotations in Handel’s hand; Pergolesi’s oratorio La fenice sul rogo (The phoenix on the pyre); La morte di S. Giuseppe, an oratorio dating from 1732–33, and long considered a dubious attribution until the appearance of this manuscript, which is entirely in the hand of the composer; a document in the hand of Joseph Haydn; Mozart’s Gavotte in B flat, K. 300, a two-page movement possibly discarded from the ballet Les petits riens he wrote for the Paris Opera in 1778, during his second visit; Boccherini’s quintets for piano and strings, opus 57, a handsome manuscript bound in three volumes (one for the piano, one for the violins, one for the viola and cello) and inscribed to the secretary general of the French government in 1799 in the hope for patronage, which was not granted. Not many Boccherini manuscripts survived, many having disappeared during the Spanish Civil War.

The nineteenth-century German component of the collection is extraordinarily impressive: Schubert (sketches for the F minor Fantasy for piano four-hand, two Lieder, two letters), Weber (an important correspondence with his namesake and fellow musician Gottfried Weber), Mendelssohn (the piano part of the D minor concerto, several choral works and Lieder, letters, an album of sketches from his tour of Scotland), Liszt (a fragment from the Réminiscences de la Juive as well as other piano works, songs, and letters), Wagner (the drafts of the texts for Lohengrin and Siegfrieds Tod, the future Götterdämmerung, three early Lieder on French texts, a fair copy of the Prize song from Die Meistersinger, the first, lithographed printing of Tannhaüser, once in the possession of the first Tannhaüser at Dresden, Joseph Tischatschek, and several letters), Schumann (a couple of songs and several letters, as well as letters by Clara), Brahms (Alte Liebe and two songs for men’s chorus, opus 41), Hugo Wolf (four songs), D’Albert, and Mahler (two songs).

Nineteenth-century Italian composers are equally well represented: Rossini (an 1819 cantata written for a state visit to Naples of the Austrian emperor), Bellini, Ponchielli (his Omaggio a Donizetti), Pa‘r, and, naturally, Verdi, with a draft of the libretto of Ernani copied out and abundantly corrected in his hand as well as more than 200 letters, including three groups to some of his important correspondents — his librettist Francesco Maria Piave, his confidant Opprandino Arrivabene, and another friend, the sculptor Vincenzo Luccardi.

Only one Chopin manuscript (the short yet beautiful Cantabile in B flat, as well as several letters) but a splendid Berlioz collection (the overture King Lear, one of his occasional pieces, many letters) heralding a vast array of French music: Halévy (the 1832 opera-ballet La tentation, as well as letters), Gounod (his two Molière operas, Le médecin malgré lui and George Dandin, the latter, unfinished and still unpublished, among other manuscripts and letters), Offenbach (an important manuscript of The Tales of Hoffmann, recently discovered, revealing some previously unknown music written and orchestrated by Offenbach for act 4, the “Venice act”; and innumerable other manuscripts and drafts), César Franck (three manuscripts, including his oratorio Les béatitudes), Saint-Saëns (the first piano trio, the oratorio The Promised Land, which he wrote for the 1913 Three Choirs Festival, and a large and important series of letters), Bizet (letters to members of the Halévy family), Duparc (8, that is more than half, of his songs), Chausson, Chabrier, Delibes, D’Indy, Lalo, Fauré (early songs and piano music as well as letters), and Reynaldo Hahn (like Offenbach a non-French-born yet quintessentially French composer).

The Massenet collection deserves more than a passing mention. It makes Yale by far the most important Massenet collection outside France, rivaled only by the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which incorporates the holdings of the Bibliothèque de l’Opéra. All the musical genres Massenet illustrated are represented: the opera, of course, with the original draft of Hérodiade (very much different in places from the work we know) and orchestral drafts for five others; oratorios (three out of the four he wrote), cantatas, stage music (a highly important if underappreciated part of his production), songs (Massenet wrote more than 250, more than any other French composer of his day), symphonic music (including his popular Scènes alsatiennes), chamber music (an apparently unpublished piano reduction of his Cello Fantasy), and piano music (an unpublished impromptu).

Other nineteenth-century composers from other countries represented in the collection by manuscripts or letters include Balfe (sketches for the opera Satanella), Rubinstein, Borodin, Tchaikovsky, Dvorák, Max Bruch, and Grieg.

Twentieth-century music is no less richly illustrated, beginning with Italian verismo: Giordano (his first, one-act opera, Marina), Mascagni (three operas, including his last, Nerone, two cantatas, family correspondence), Leoncavallo (four complete operas, a large part of a fifth, four operettas, and correspondence), Puccini (sketches for Tosca, Butterfly, La fanciulla del West, and important letters). Post-verismo is also generously served, with Respighi (especially arrangements and orchestrations) and Wolf-Ferrari (a good half of his archive, comprising most of his opera, including sketches for Sly, recently revived for Placido Domingo in Washington, D.C., and at the Metropolitan Opera).

Possibly the greatest treasure of the entire collection is the manuscript of Pelléas, the complete piano draft, showing important deletions and revisions; other Debussy riches include several songs, important letters, and a manuscript of the ballet Jeux with annotations by Diaghilev and Nijinsky. Ravel is present with several piano pieces, his orchestrations of Debussy, transcriptions of Mussorgsky, and an extensive collection of letters; Roussel with drafts for Padmâvati and the operetta Le testament de la tante Caroline; Satie with an important manuscript for Parade, a sonnerie for two trumpets, and drafts for an unrealized opera on Paul et Virginie; Poulenc with manuscripts for Les biches, the song collection Banalités, the flute sonata, and several other pieces, as well as with correspondence with his friend and disciple Pierre Bernac and fellow Six Georges Auric and his wife Nora.

British music of the past century is very well represented in the collection: Elgar, Edward German, Granville Bantock, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Lord Berners (The Triumph of Neptune, written for the Ballets russes). In 1985, Frederick R. Koch acquired the virtually complete musical archive of William Walton, including parts of Façade, the two symphonies, his operatic masterpiece Troilus and Cressida, and the Variations on a Theme by Hindemith. In a more popular vein, Noel Coward is present with several manuscripts and the entirety of his colorful and only partially published journals.

One should not leave out Richard Strauss (letters and manuscripts of songs, including the recently discovered “Malven,” the last song he wrote, which surfaced in the papers of the soprano Maria Jeritza, one of the composer’s favorite interpreters, after her death), Villa Lobos (an arrangement for violin and piano of his Fantasia de movimentos mistos), Glazunov (the Finnish Fantasy), Sibelius (three songs, one both in the piano and orchestral versions), Dukas (his cantata Velléda, the chorus with orchestra “La fleur,” and sketches for Polyeucte), and Stravinsky (the aforementioned Renard, the Cinq pièces faciles, the Étude for pianola, all from the collection of his Chilean benefactress Eugenia Errasuriz).

Finally, two important collections of papers of two musicologists who were both at some point editors of the Chesterian in London; one French, G. Jean-Aubry, a friend of Debussy, and the other, Rollo Myers, British, though also a specialist in Debussy and French music in general.

The presence of such an extraordinary collection has had several consequences as well as creating new responsibilities for the Beinecke. It has brought to the library a new, international constituency of researchers, musicologists and musicians, to whom the collection is made accessible either in our reading room or through photocopies. It has opened new possibilities for students of music at Yale, who have access to the study of original manuscripts on a scale and in a depth unprecedented before. And it has opened new vistas for collection development for the Beinecke in the field of music, thanks in large part to generous donors such as Professor Richard French, 1973 Hon., of the Department of Music, who at his death in the spring of 2001 made the Beinecke Library the beneficiary of his will, thus giving us our first fund devoted (at least in part) to the purchase of music, the Richard and Edith French Fund.

It has been possible, in particular, to acquire material that matches closely or complements manuscripts already present in the Frederick R. Koch Collection. Next to the annotated manuscript of Jeux, there is now in the Beinecke another copy of the piano score of Debussy’s ballet, also annotated throughout in the hands of Diaghilev and Nijinky, with additional markings by Debussy himself and Bakst (both the Koch and the Beinecke manuscripts were once in the collection of Serge Lifar). One of Debussy’s most important correspondences was with his close friend the poet and novelist Pierre Louÿs, author of the Chansons de Bilitis: this correspondence was incompletely published in the 1940s, then dispersed. Frederick R. Koch had been able to reconstitute part of it, and the Beinecke has added a few more letters (from both sides). Next to the full-score Koch manuscript of Giordano’s Marina, his submission for the second Sonzogno competition, the one won by Mascagni for Cavalleria rusticana, there is now the short-score manuscript, purchased in 2000, while another Giordano manuscript was purchased in London the following year, that of Mese Mariano, also a one-act opera, of 1910. The draft manuscript of Puccini’s song Inno a Diana has been supplemented by a corrected fair copy, purchased at Sotheby’s three years ago. One of Puccini’s most important correspondents in the last twenty years of his life was Sybil Seligman, whose husband David headed the family bank in London. The three hundred or so letters Puccini wrote to her were partially published by her son, Vincent Seligman, in English translation, in a 1938 memoir entitled Puccini Among Friends, and then dispersed (Vincent Seligman, for obvious reasons, was keen to deny that his mother and Puccini were sexually involved— whereas most biographers are convinced that they were). The Frederick R. Koch Collection includes several of those letters, and the Beinecke