IN THE DIGITAL LIBRARY | ALSO IN BEINECKE CONNECTIONS | RELATED MATERIALS | BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING

This guide spotlights works written by incarcerated American artists available in Beinecke’s Digital Library. Many more materials relating to incarceration are available in Beinecke Collections, and the spotlighted digitized objects all find their place in the broader context of the collections in which they are held. The guide is organized in chronological order, and includes both works in the digital library and works in Beinecke collections that have not yet been digitized.

Engaging with the works of incarcerated writers necessitates reckoning with the legacy of slavery in the United States. Many objects from Beinecke Collections (in this guide, particularly The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict and Bondswoman’s Narrative) display the slippery relationship between plantation and prison, which were not just chronologically consecutive but rather bled into each other and necessarily coexisted at various points in American history.

In many cases, the provenance stories of these objects are complex and charged. In her 2020 book Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, Dr. Nicole Fleetwood discusses how

“many currently and formerly incarcerated artists are not in possession of their art…for various reasons that all have to do with the extreme inequalities and exploitation that incarcerated people suffer, art made in prison is sent to relatives, traded with fellow prisoners, sold or “gifted” to prison staff, donated to nonprofit organizations, and sometimes made for private clients. Unlike artists who work outside prison, who are able to document their creations, incarcerated artists often are unable to photograph or make copies of their work.”

This is frequently true of the manuscripts spotlighted in this guide: certain objects made by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals are held by their incarcerators, lawyers, family members, or others. For example, the Sketchbook(s) by Indian Prisoners at St. Augustine are held in the papers of Robert Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Erica Huggins’ “Prison Writings” find their home in the Catherine Roraback Collection of Ericka Huggins Papers, documenting the activities of both the Attorney Roraback and Huggins during the New Haven Black Panther trials. Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict came to Beinecke from an estate sale in Rochester, New York. This requires us to interrogate how the archive itself is implicated in these processes of removal, acquisition, and display.

From the Yale University Library Statement on Harmful Language in Archival Description: Yale University aims to create archival description – including finding aids, catalog records, and other metadata – that is inclusive, respectful, and does not cause harm to those who interact with our collections. This includes those who create, use, and are represented in the collections we steward. We acknowledge that our existing description may contain language that is racist, sexist, colonialist, homophobic, or that uses other offensive terms that may cause harm. This language may result from archival description that has been created over the years by creators of collection material, previous stewards, or by Yale staff since acquisition.

READ the statement in its entirety: Yale University Library Statement on Harmful Language in Archival Description

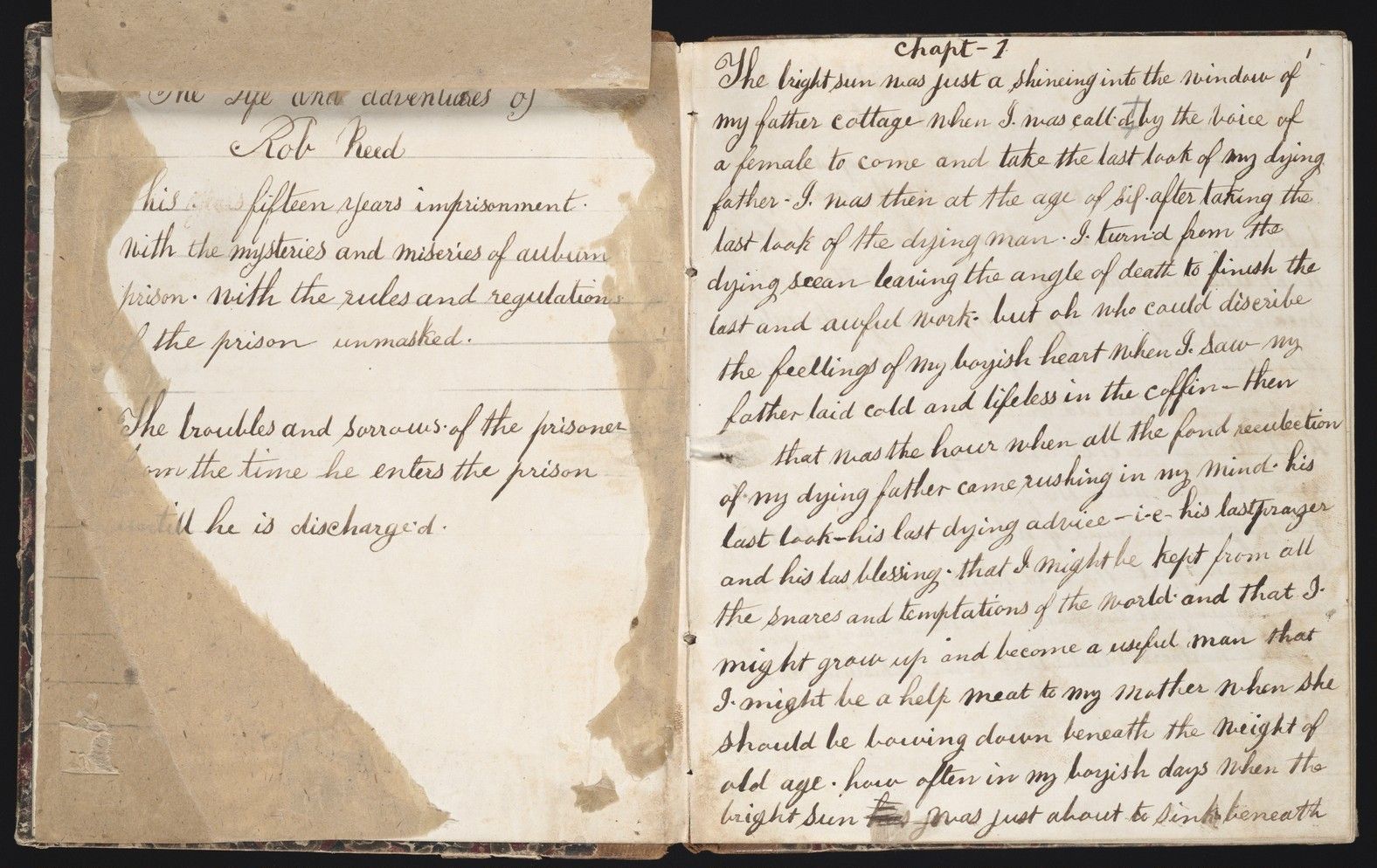

The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict, or the Inmate of a Gloomy Prison

by Austin Reed (c. 1858)

Digital Library | Orbis | Additional Reading 1 | Additional Reading 2 | Additional Reading 3

In this memoir, the first known prison narrative by an African-American writer, written around 1859, Austin Reed attributes the wayward course of his life to the tragic loss of his father at the age of six. Reed recounts his experiences at the New York House of Refuge, the first juvenile reformatory in the United States, and later in New York’s Auburn State Prison. Reed provides a wealth of vivid detail about his incarceration at Auburn, including a description of the horizontal black-and-white striped uniform which originated at the prison: “streaked clothes of shame and disgrace.” Released from Auburn on May 1, 1842, he was reincarcerated there before the close of the year, “I return’d home and committed a crime wich brought me back to a gloomy prison.” This unparalleled narrative is a unique resource documenting the lives of African-American prisoners in antebellum America. Born circa 1823 in Rochester, New York, Austin Reed wrote under the pseudonym “Rob. Reed.” (Source.)

In this memoir, the first known prison narrative by an African-American writer, written around 1859, Austin Reed attributes the wayward course of his life to the tragic loss of his father at the age of six. Reed recounts his experiences at the New York House of Refuge, the first juvenile reformatory in the United States, and later in New York’s Auburn State Prison. Reed provides a wealth of vivid detail about his incarceration at Auburn, including a description of the horizontal black-and-white striped uniform which originated at the prison: “streaked clothes of shame and disgrace.” Released from Auburn on May 1, 1842, he was reincarcerated there before the close of the year, “I return’d home and committed a crime wich brought me back to a gloomy prison.” This unparalleled narrative is a unique resource documenting the lives of African-American prisoners in antebellum America. Born circa 1823 in Rochester, New York, Austin Reed wrote under the pseudonym “Rob. Reed.” (Source.)

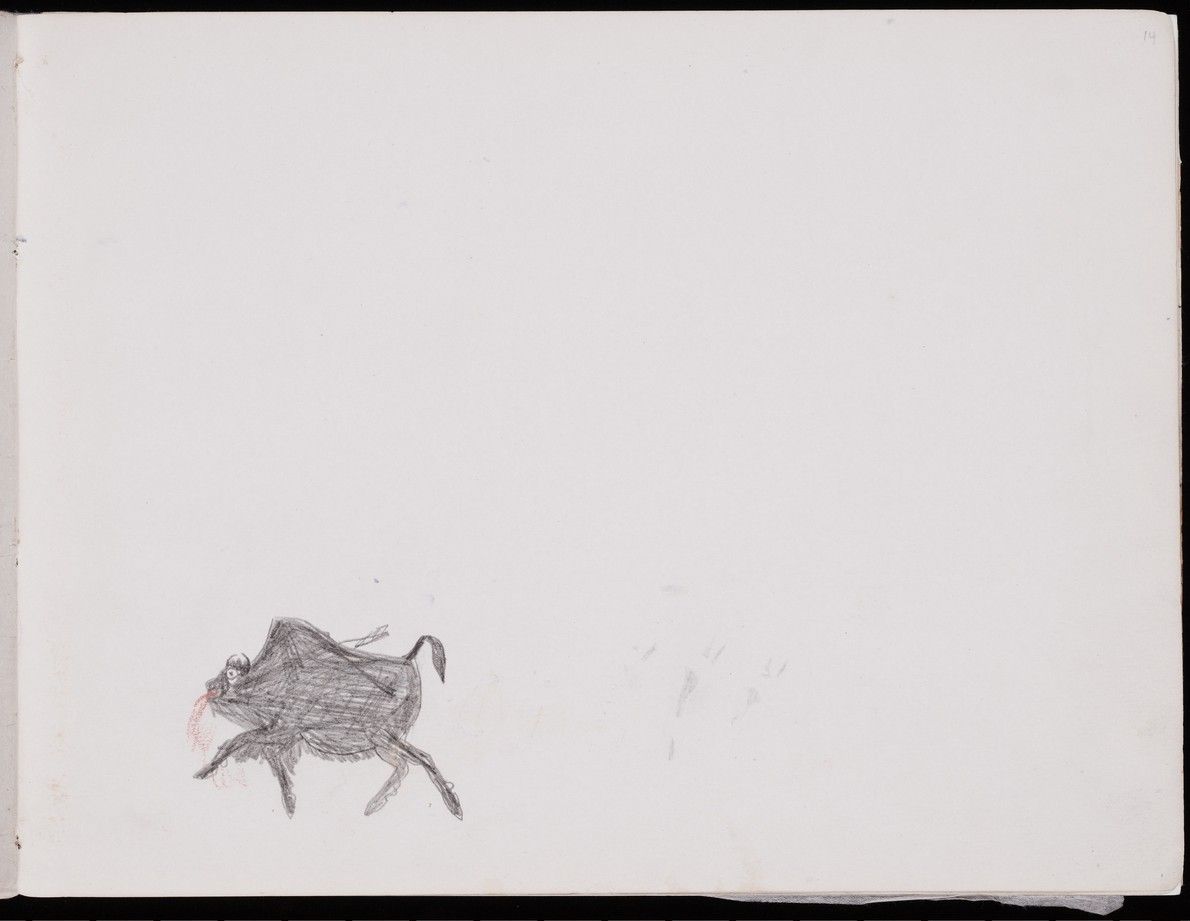

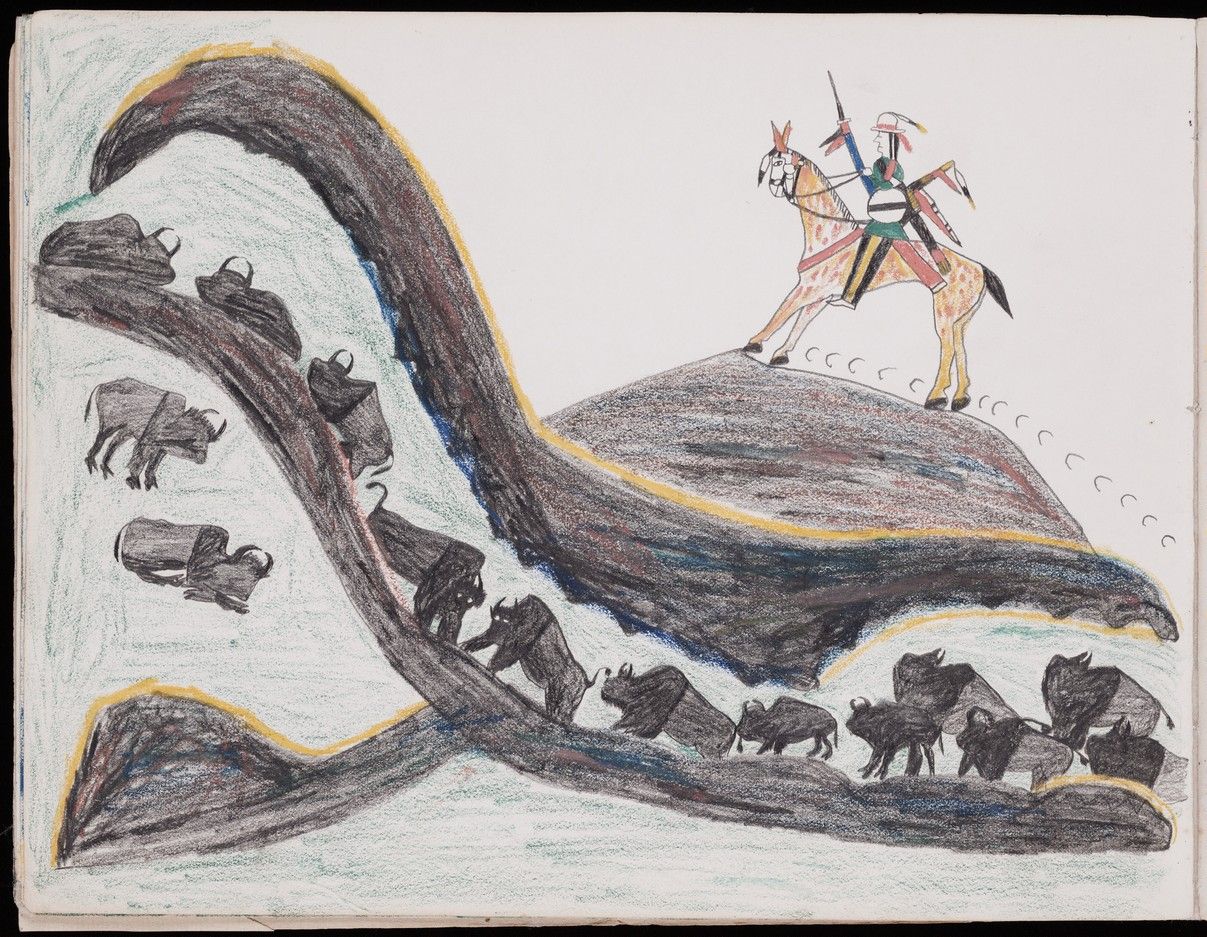

Sketchbooks

by unnamed prisoners at St. Augustine, Florida (c. 1876)

in the Richard Henry Pratt Collection

Digital Libray 1 | Digital Library 2 | Orbis | Finding Aid

Manuscript inscription states, “Drawings made by the Indian Prisoners confined in Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Fla. 1875-1878, representing themselves and incidents in their lives.”

Sketchbook

by Howling Wolf (c. 1876)

Digital Library | Orbis

Howling Wolf was a Cheyenne warrior and son of the Cheyenne chief Eagle Head. He was imprisoned from 1875 to 1876 at Fort Marion, Saint Augustine, Florida, with other “hostile” Plains Natives. This sketchbook contains sixteen pencil, crayon, and ink drawings, depicting scenes at Fort Marion, and of Cheyenne life on the Plains, including buffalo hunts and celebrations. The note, “Drawn by Howling Wolf (Cheyenne) Oct 1876 Fort Marion” is written in pencil inside the front cover in an unidentified hand.

Poston Notes and Activities

from the Mary Burford Courage papers related to the Poston Relocation Center, Arizona (c. 1943)

Digital Library | Orbis

The Poston Relocation Center in Arizona was the largest of the ten Japanese American internment camps operated by the United States war Relocation Authority during World War II, 1942-1945. This newspaper was written and printed by individuals incarcerated at Poston.

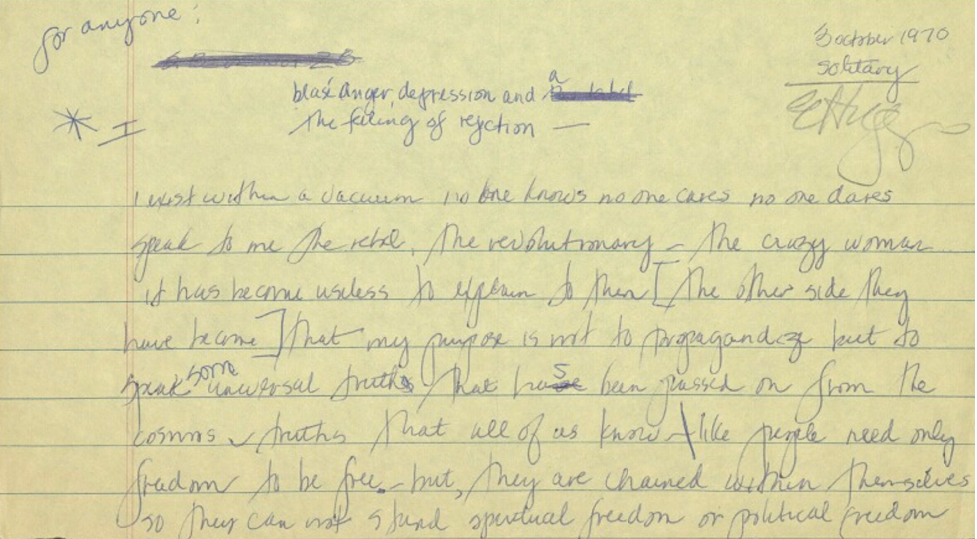

Prison Writings

by Ericka Huggins (c. 1969)

from the Catherine Roraback Collection of Ericka Huggins Papers

Digital Library | Orbis | Finding Aid | Related Materials

Materials in the Catherine Roraback collection of Ericka Huggins papers document the activities of both Catherine Roraback and Ericka Huggins during the New Haven Black Panther trials. A majority of the collection contains Catherine Roraback’s legal files related to Ericka Huggins’s trial, including memoranda on prison conditions, statements, depositions, affidavits, and FBI reports. Materials belonging to Ericka Huggins includes poems, correspondence, and other writings created during her imprisonment. Communist reading material requested by Huggins such as The Selected Writings of Mao Tse-Tung (1968) are also included. (Source.)

A Tale of a Walled Town and Other Verses

by Prisoner B. 8266 (of an unidentified penitentiary) (c. 1921)

The full text of this book of poems is available online via Hathitrust.

Shadows

A monthly magazine, written, edited, and printed by inmates of the Oregon State Penitentiary, Salem, Oregon. (c. 1936-)

Shadows is “a monthly magazine dedicated to those who would salvage rather than destroy.”

The Angolite

Published by and for the inmates of the Louisiana State Penitentiary (c. 1952-)

The Angolite is a magazine edited and published by individuals incarcerated at the Louisiana State Penitentiary (Angola) in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana.

Joseph Longstreth papers relating to Caryl Chessman (c. 1953-1990)

Caryl Chessman (1921-1960) of Saint Joseph, Michigan, was sentenced to death in California for a series of crimes committed in the Los Angeles area in 1948 January. Charged as the “Red Light Bandit”, he was convicted under the “Little Lindbergh law”, which defined kidnapping as a capital offense under certain circumstances. While spending 12 years on death row, fighting his conviction, Chessman wrote 4 memoirs: Cell 2455 death row (1954), Kid was a killer (1960), The face of justice (1957), and Trial by ordeal (1955). The collection includes correspondence, writings, newspaper clippings, and other papers on publishing and legal matters related to Chessman.

Poems from Prison

by Etheridge Knight & Preface by Gwendolyn Brooks (c. 1968)

The full text of Knight’s book of poems is available online via Hathitrust.

Return Me To My Mind

by Stanley Eldridge (c. 1970)

More information regarding Eldridge’s book of poems is available via Brown Library’s Website.

Who took the weight? Black voices from Norfolk Prison: Norfolk Prison brothers.

Foreword by Elma Lewis. Drawings by Alfred Howell, Jr., photos. by Ted Polumbaum. (c. 1972)

Poems, plays and short stories by men at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution, Norfolk.

A Flower Blooming in Concrete

by Willie J. Williams (c. 1976)

The full text of Williams’ book of poems is available online via Hathitrust.

Dear Stranger/The Wayfarer: poems

by Ralph C Hamm (c. 1979)

This book of poems was written when Hamm was in his twenties, incarcerated in the America-Walpole State Prison in South Walpole, Massachusetts.

In Total Resistance

Statements and poetry from Leonard Peltier, Standing Deer, and Bobby Garcia (c. 1980)

This booklet was written in memory of Bobby Gene Garcia, who suspiciously died in Terre Haute Federal Prison in December, 1980. Peltier wrote from the Marion Federal Penitentiary, “to the people who struggle for their freedom, I embrace you and send you my love and strength.” The full text is available online via The Freedom Archives.

Reachin’ Out

by “Christians serving time in the Arizona State Prison” (c. 1984)

Reachin’ Out is a booklet that includes “a collection of testimonials, in the form of poetry and praise, written by Christians serving time in the Arizona State Prison.”

Damien Echols diaries, circa 2006-2007

Three autograph diaries describing Damien Echols’s life in prison in Varner, Arkansas, circa 2006-2007. Echols describes conditions in prison, his mental health, interactions with other prisoners on death row, and his creative projects, including painting, poetry, songwriting, and collage. He also details developments in his legal case, including the discovery of new evidence, attempts to get DNA evidence from the crime scene tested, and his wife Lorri Davis’s interactions with lawyers and forensic investigators. Additionally, Echols describes his occult beliefs and practices, which included elements of Thelema, magic, neopaganism, and Catholicism. Includes tipped-in stickers, stamps, and cards.

Documenting the Experience of Incarcerated Individuals

Drawings of the Amistad Prisoners, New Haven

by William H. Townsend (c. 1839)

Orbis | Digital Library | Youtube

In 1839, the Spanish slave ship Amistad set sail from Havana to Puerto Principe, Cuba. The ship was carrying 53 Africans who, a few months earlier, had been abducted from their homeland to be sold as slaves. The captives revolted against the ships crew, killing the captain and others, but sparing the life of the ships navigator so that he could set them on a course back to Africa. Instead, the navigator surreptitiously directed the ship north and west. After several weeks, the Amistad was seized by the U.S. Navy off the coast of Long Island and the Africans were transported to New Haven to await trial for mutiny, murder, and piracy.

Slavery advocates held that the Amistad prisoners were slaves and thus they should be punished for their uprising and immediately returned to Cuba. Abolitionists, on the other hand, argued that though slavery was legal in Cuba, the importation of slaves from Africa had been outlawed; thus, they claimed, the prisoners were not slaves, but freemen who had been kidnapped and thus had every right to escape their captors and even to use violence to do so. The case was important to the proslavery-abolitionist debates that were raging in the U.S., and to the international debates about treaty obligations with regard to slavery and the legality of the international slave trade.

After two years of legal battles, their case was successfully argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1841 by former President John Quincy Adams and the Amistad captives were freed. They returned to Sierra Leone in 1842. New Haven resident William H. Townsend made pencil sketches of the Amistad captives while they were awaiting trial. (Source.)

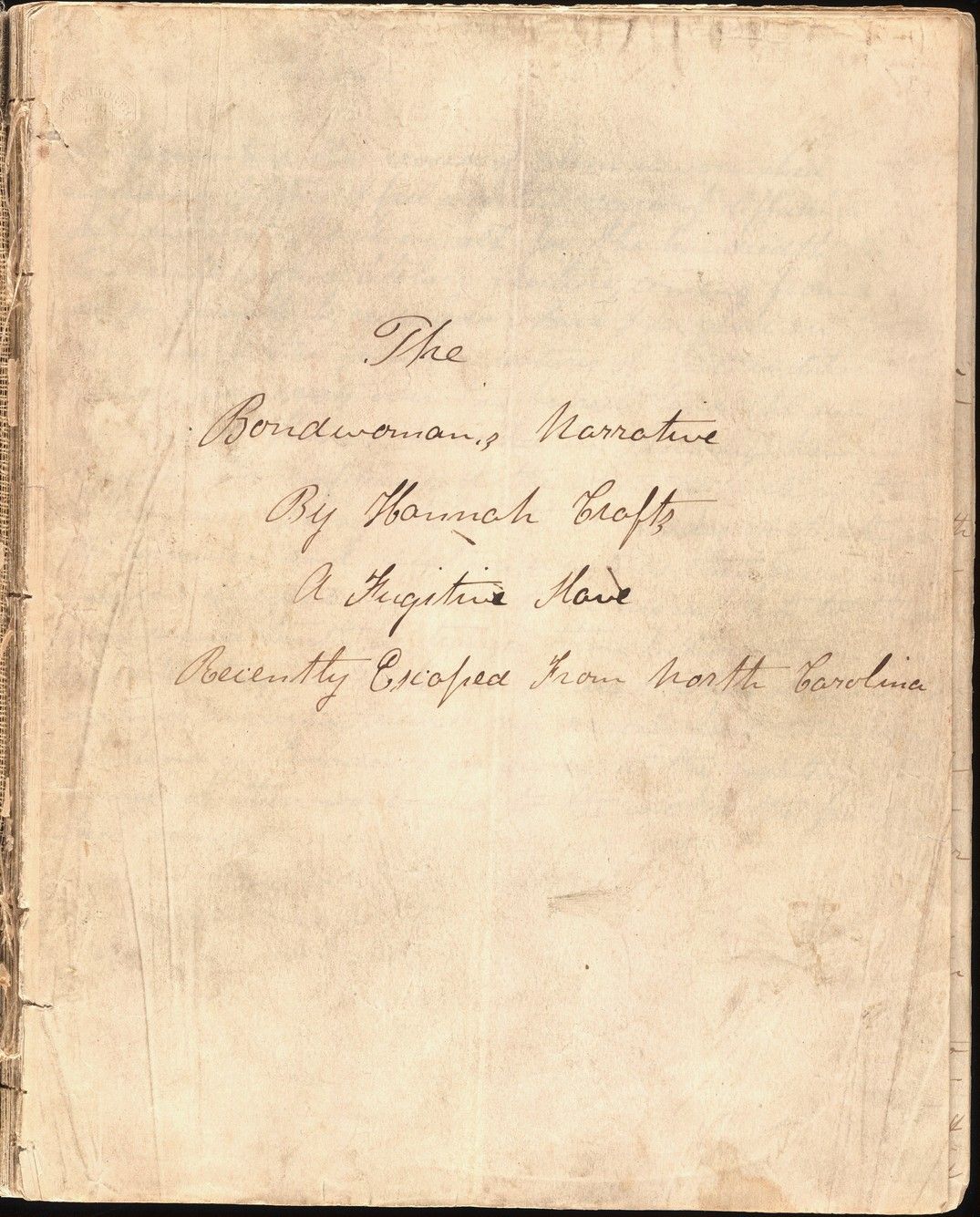

Bondswoman’s Narrative

by Hannah Crafts (c. 1853-1861)

Digital Library | Orbis | Additional Resources

“The Bondwoman’s Narrative,” a fictionalized autobiography, is thought to be the first novel written by an African American woman and the only known novel written by a fugitive slave. Written in the gothic and sentimental style favored at the time, “The Bondwoman’s Narrative” is the story of a girl whose escape from a North Carolina plantation leads to a series of adventures and obstacles, including passing as a young white man and encounters with slave hunters tracking fugitive slaves. She eventually finds freedom and safety in the North. Gift of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (Yale 1973). (Source.)

Photographs of the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi

by Estelle Caro Eggleston (c. 1930-1938)

Orbis | Digital Library

Photographs attributed to Estelle Caro Eggleston that depict personnel, incarcerated people, agricultural fields, and buildings at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi, circa 1930-1938. Many of the images depict group portraits of nurses employed by the prison hospital. An image depicts incarcerated individuals eating a meal by the train depot of Black Bayou, Mississippi. The photographs are accompanied by a certificate of merit for an honorable mention award earned by Eggleston in the first annual Newspaper National Snapshot Awards sponsored by the Eastman Kodak Company in November 1935.

The Black Panthers Trial: Courtroom Sketches

by Robert Templeton (c. 1971)

Orbis | Digital Library | Collection Guide

Drawings documenting the Black Panthers trial in New Haven in 1971; the sketches were created by Connecticut artist, Robert Templeton. Because the courtroom was closed to artists and photographers, Templeton’s sketches were made surreptitiously, without the permission of the court; his drawings are, perhaps, the only visual record of the courtroom during this critical case. The collection includes small preliminary notebook sketches made in the courtroom as well as larger, finished drawings later displayed on television news broadcasts. Defendants Bobby Seale and Erica Huggins, Prosecutor Arnold Markle, and Judge Harold Mulvey are among the subjects represented.

West 57th: Leonard Peltier (c. 1991)

from the Richard Erdoes papers

Digital Library | Orbis

This episode of the CBS show West 57th was part of the heavy media coverage surrounding Peltier’s July 1991 hearing. In the video, Appeals Judge Gerald Heaney, who’d written the Eighth Circuit Opinion denying Peltier’s appeal for a new trial, called the Peltier case “the toughest decision I ever had to make in 22 years on the bench,” and said he “felt uncomfortable” with his decision (source). Materials related to Peltier in the Erdoes papers can be found here.

One Big Self

by C.D. Wright and Deborah Luster (c. 2003)

Orbis | Text | Online Text | Manuscripts in the C.D. Wright Papers

In 1998, lifelong friends and frequent collaborators poet C. D. Wright and photographer Deborah Luster made numerous visits to prisons in Louisiana. With the poet acting as an observer and as a “factotum” to the photographer, they set to work making portraits of the incarcerated people they encountered. Individuals were invited to “present themselves as they would be seen, bringing what they own or borrow or use: work tools, objects of their making, messages of their choosing, their bodies, themselves.” Of making the individual photographs, Luster has written: “I wanted this to be as collaborative an enterprise as possible.” Over a period of about five years, Luster photographed tens of thousands of incarcersted individuals, giving her subjects some 25,000 photographic prints to share with family or trade with others. As photographs were made, Wright spoke to subjects, listened to their stories, came to understand something of their experiences; she recorded details about the prisons, their routines, rituals, and artifacts. She kept notes—recording conversations, jotting down overheard speech, collecting documents. In 2003, Luster and Wright published One Big Self: Prisoners of Louisiana, collecting Luster’s photographs and Wright’s poems—lyrical works employing the rhythms of guards counting incarcerated people, braiding together many voices, assembling fragments of narrative and emotion. The resulting work may be understood as a collective visual and linguistic portrait of an incarcerated community, a collaborative recording of the personal experiences of two artists encountering that community, and, as Luster writes, as “a document to ward off forgetting.” (Description by Nancy Kuhl)

Bibliography & Further Reading

Hamilton College. “American Prison Writing Archive.” Accessed November 18, 2020. https://www.hamilton.edu//academics/centers/digital-humanities-initiative/projects/american-prison-writing-archive.

“American Prison Writing Archive at Hamilton College.” Accessed November 18, 2020. http://apw.dhinitiative.org/

Belcher, Ellen. “LibGuides: New York Prisons and Jails: Historical Research: Prison Newspapers - throughout the U.S.” Accessed November 18, 2020. https://guides.lib.jjay.cuny.edu/NYPrisons/PrisonNewspapers.

Fleetwood, Nicole R. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674250925.

Franklin, H. Bruce. American Prisoners and Ex-Prisoners, Their Writings: An Annotated Bibliography of Published Works, 1798-1981. Westport, Conn: L. Hill, 1982.

Justice Arts Coalition. “Gallery #13.” Accessed November 18, 2020. https://thejusticeartscoalition.org/gallery/.

PRISM international. “Marking Time: An Interview with Nicole Fleetwood.” Accessed November 18, 2020. https://prismmagazine.ca/2020/06/16/marking-time-an-interview-with-nicole-fleetwood/.

Meissner, Caits. “Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration: A Dialogue with Nicole R. Fleetwood.” PEN America (blog), June 23, 2020. https://pen.org/interview-with-nicole-fleetwood/.

PEN America. “Prison & Justice Writing,” October 27, 2016. https://pen.org/prison-writing/.

Small, Zachary. “What Curators Don’t Get About Prison Art,” October 18, 2019. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/prison-art-shows-essay/.

“The Academic Library in Prison Higher Education: Merced College at Valley State Prison and Central California Women’s Facility | Council of Chief Librarians - California Community Colleges.” Accessed November 12, 2020. https://cclibrarians.org/outlook/april-2020/academic-library-prison-higher-education-merced-college-valley-state-prison-and.

- Gabrielle Colangelo Y ‘21, Yale Collection of American Literature Student Research Assistant